André-Charles Boulle, le joailler du meuble (the "furniture jeweller"), became the most famous French cabinetmaker and the preeminent artist in the field of marquetry, also known as "inlay". Boulle was "the most remarkable of all French cabinetmakers". Jean-Baptiste Colbert (29 August 1619 – 6 September 1683) recommended him to Louis XIV of France, the "Sun King" (r. 1643–1715), as "the most skilled craftsman in his profession". Over the centuries since his death, his name and that of his family has become associated with the art he perfected, the inlay of tortoiseshell, brass and pewter into ebony. It has become known as Boulle work, and the École Boulle (founded in 1886), a college of fine arts and crafts and applied arts in Paris, continues today to bear testimony to his enduring art, the art of inlay.

In 1677, on his marriage certificate, André-Charles Boulle gave his birth date, for posterity, as being 11 November 1642. No other document corroborates this birth in Paris. The historians M. Charles Read, H.-L. Lacordaire and Paulin Richard have determined that his father was the Protestant Jan (or Jean/Johann) Bolt (or Bolte/Boul/ Bolle) but at his own (Catholic) marriage, André-Charles Boulle named his father as "Jean Boulle". André-Charles Boulle's marriage at Saint Sulpice and burial in 1732 at Saint-Germain-l'Auxerrois are but two of many lifetime inconsistencies with his Protestant 'provenance', most easily explained by the ongoing persecution of Protestants. His parentage with the Protestant Boulles from Marseille, the Sun King's Historian needs clarification and Coliès, in his Bibliothèque Choisies confirms a Marseillais relative as being the author of a History of Protestantism, called Essay de l'histoire des Protestants Distingués Par Nation (1646).

In the absence of a birth document, three factors play a critical part in the mystery surrounding Boulle's parentage.

The first is that foreign artists flocking to the Sun King's Court were keen to be naturalised French subjects to 'fit in' and would, like Jean-Baptiste Lully the Royal Musician (28 November 1632 – 22 March 1687), have changed their names. For Lully, it was from "Giovanni Battista Lulli" to "Jean-Baptiste Lully") but at his marriage, he falsely declared his father's name to be Laurent de Lully, gentilhomme Florentin [Florentine gentleman]". This historical background makes it difficult for the historian to identify which of the many Jean Boulles, Jean Bolles, Johann Bolts or even 'Jean Boulds' on record was André-Charles Boulle's true father. Some of these are of Catholic French origin, some are French Protestants and some are from Gelderland in Holland.

The second factor is that André-Charles Boulle's birth date is almost certainly inacurrate. Despite his genius (or perhaps because of it) André-Charles Boulle was a demonstrably poor administrator and poor with dates and specifically in respect of his age. His children were no different, declaring him to be 90 Years old when he died. This is highly unlikely.

The third and perhaps most telling factor adding to the overall confusion about Boulle's parentage was that in October 1685 (a mere 8 years after his marriage), Louis XIV renounced the Edict of Nantes and declared Protestantism illegal with the Edict of Fontainebleau. All Protestant ministers were given two weeks to leave the country unless they converted to Catholicism. Louis XIV ordered the destruction of Huguenot churches, as well as the closure of Protestant schools. This made official the persecution of Protestants already enforced since 1681 and it led to around 400,000 fleeing the country.

Jean-Baptiste Lully demonstrates, by his documented actions, that marriage was a propitious time to tidy up provenance. Within the context of the times, it is natural to expect that as well as ensuring his father's Catholic name was recorded for posterity, André-Charles Boulle 'tidied' up his own place and date of birth. This made him older, for motives we do not yet comprehend. There is also the definite possibility, as yet unexplored by historians, that André-Charles Boulle was born in Holland. It would explain a lot of the confusion around his parentage. The salient fact is that we only have André-Charles Boulle's word that he was born in Paris in 1642.

André-Charles Boulle's Protestant family environment was a rich and artistic milieu totally consistent with the genius of the Art he was to produce in later years. His father, Jean Boulle (ca 1616-?), was cabinetmaker to the King, had been naturalised French in 1676 and lived in the Louvre, by Royal Decree. His grandfather, Pierre Boulle (ca 1595–1649), was naturalised French in 1675, had been cabinetmaker to Louis XIII and had also lived in the Louvre. André-Charles was thus exposed to two generations of illustrious artists, master craftsmen, engravers, cabinetmakers and, indeed, family all directly contracted by the King. As pointed out by the historians M. De Montaiglon and Charles Asselineau, this entourage included his aunt Marguerite Bahusche (on his mother's side) who was a famous painter in her own right, married to another very famous artist, Jacques Bunel de Blois, Henri IV's favourite painter. Others who were appointed by the King and worked with the two preceding generations of Boulles from their ateliers in the Louvre included the painter Louis Du Guernier (1614–1659), the embroiderers Nicolas Boulle and Caillard and the goldsmith Pierre de la Barre.

There is virtually nothing on André-Charles Boulle's youth, upbringing or training apart from a solitary Notarial Act dated 19 July 1666 (when he was supposedly 24 years old) agreeing a 5-year apprentice's contract for a 17-year-old nephew, François Delaleau, Master Carpenter from L'Abbaye des Celestins de Marcoussis in Paris. André-Charles Boulle's own apprenticeship was therefore most likely to have occurred within the focused confines of his father's atelier at the Louvre. Here, in any event, he was closest to the Sun King and to Jean-Baptiste Colbert who discovered him.

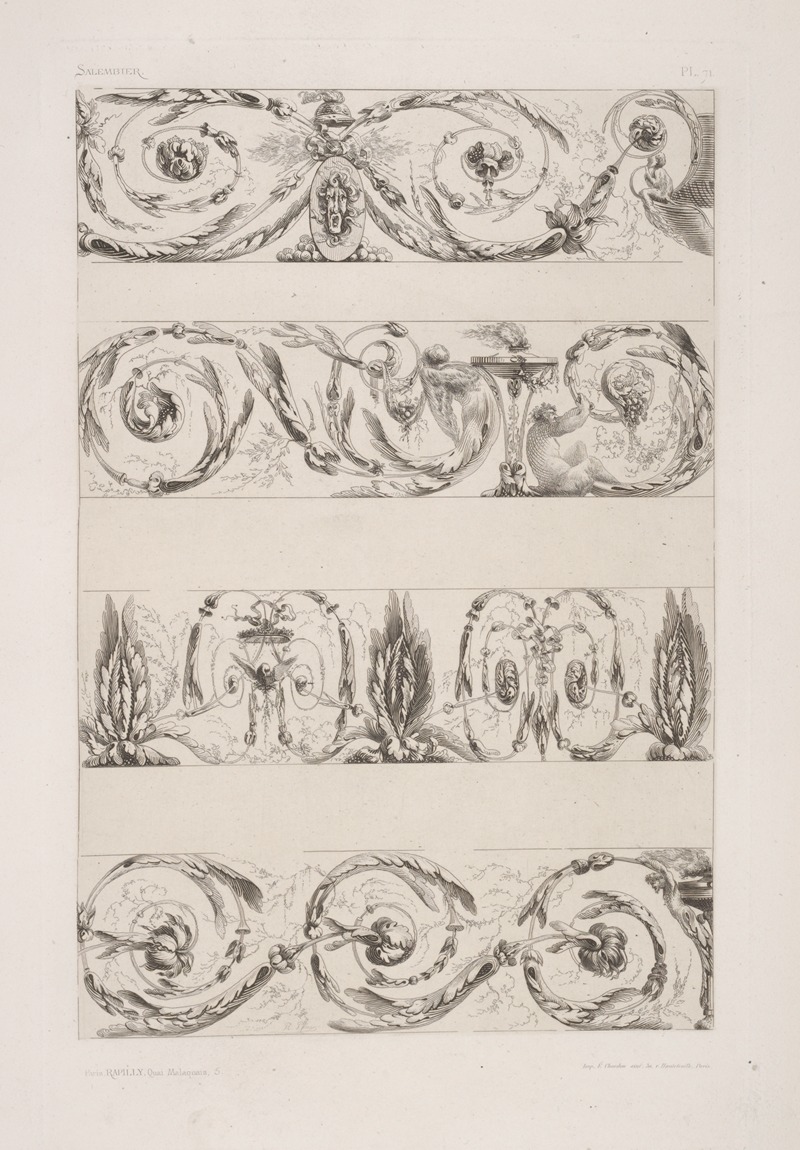

In 1672, by the age of 30, Boulle had already been granted lodgings in the galleries of the Louvre which Louis XIV had set apart for the use of the most favoured among the artists employed by the Crown. To be admitted to these galleries signified a mark of special Royal favour and also freed him from the restrictions imposed by the trade guilds. Boulle received the deceased Jean Macé's lodgings on the recommendation of the Minister of Arts, Jean-Baptiste Colbert, who described Boulle as le plus habile ébéniste de Paris. The Royal Decree conferring this privilege describes Boulle variously as a chaser, gilder and maker of marquetry. Boulle received the post of Premier ébéniste du Roi.

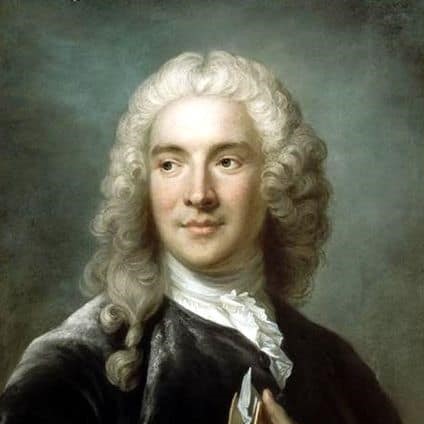

Boulle initially had aspirations to be a painter but according to one of his close friends, Pierre-Jean Mariette (7 May 1694 – 10 September 1774), he was forced by his cabinetmaker father, Jean Boulle, to develop other skills. This may explain a sense of 'missed vocation' and resultant 'passion' and utter dedication to the collection of prints and paintings, which nearly ruined him…

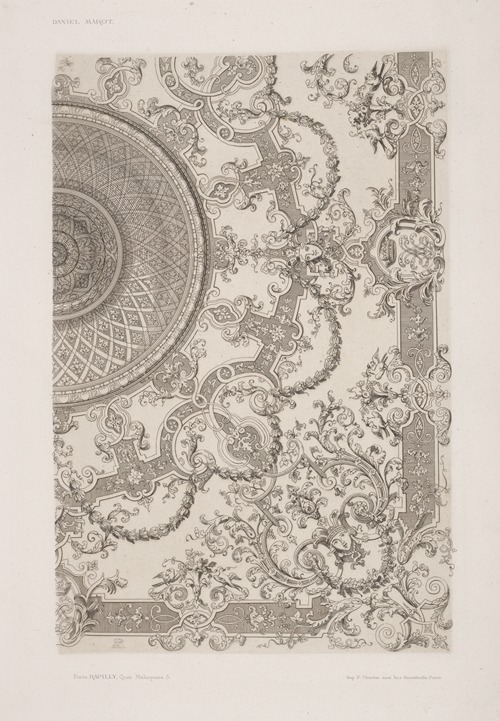

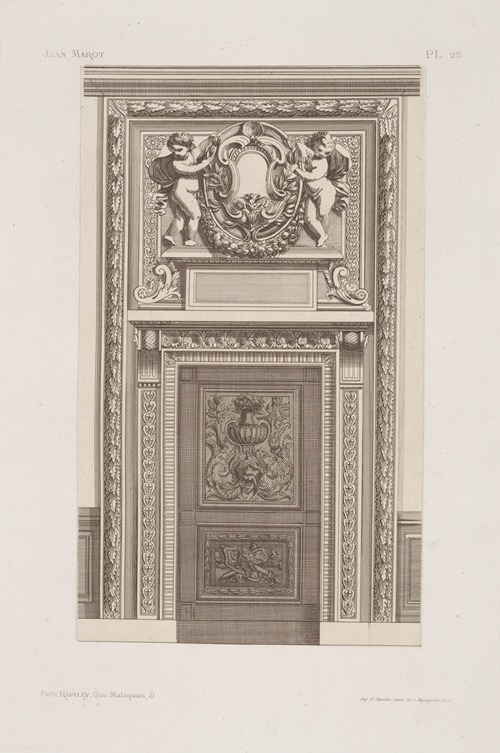

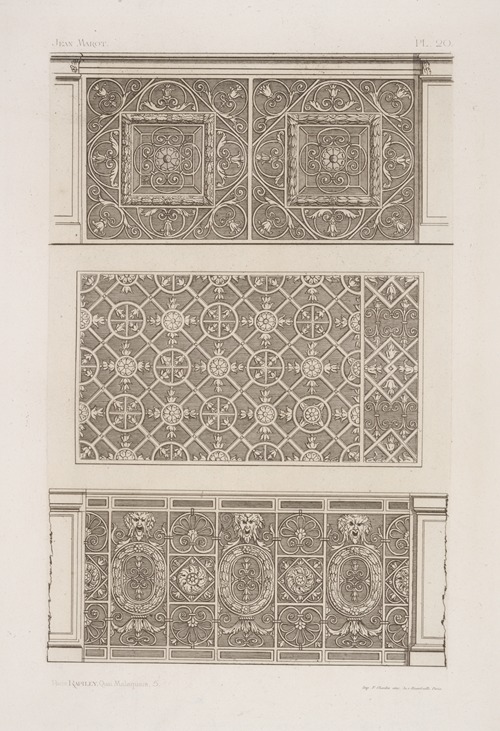

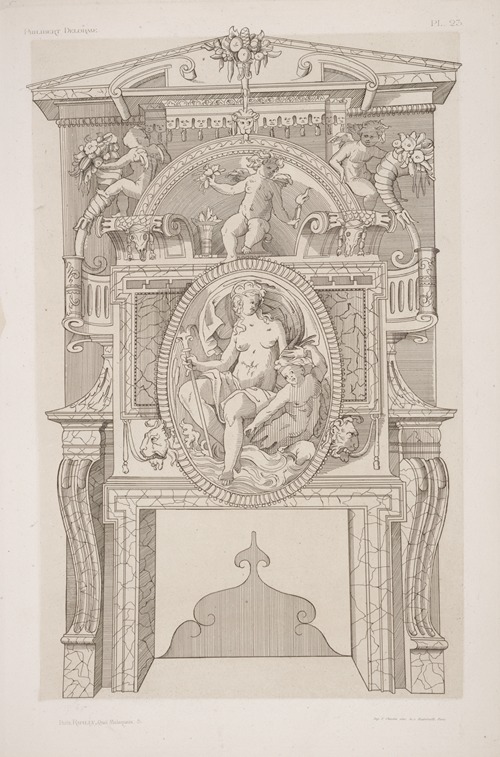

The first payment on record to him by the crown (1669) specifies ouvrages de peinture and Boulle was employed for years on end at the Versailles, where the mirrored walls, floors of wood mosaic, inlaid paneling and marquetry in the Cabinet du Dauphin (1682–1686) came to be regarded by such as Jean-Aimar Piganiol de La Force ( 21 September 1669 – 10 January 1753 ) as his most remarkable work. The rooms were dismantled in the Late 18th century and their unfashionable art broken up. More recently, a partial inventory of the Grand Dauphin's decorations at the Palace of Versailles has come to light at the National Archives in Paris.

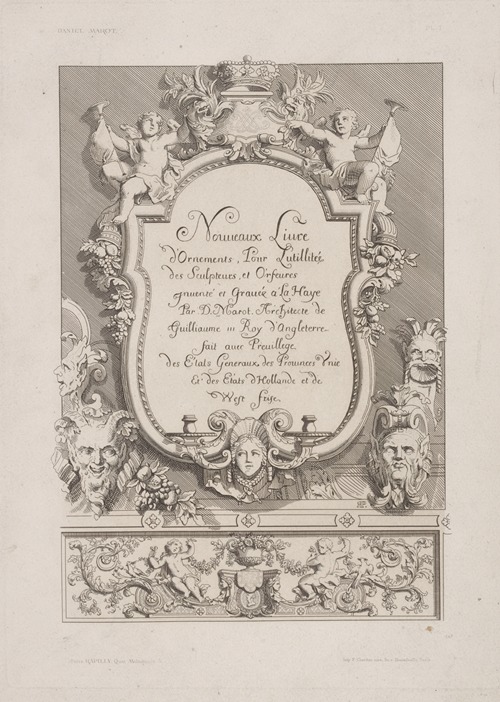

Boulle carried out numerous royal commissions for the "Sun King", as can be seen from the records of the Bâtiments du Roi and correspondence of the marquis de Louvois. Foreign Princes, French Nobility, government ministers and French financiers flocked to him offering him work, and the famous words of the abbé de Marolles, Boulle y tourne en ovale became a well established saying in the literature associated with French cabinetmaking. Professor C.R. Williams writes, There was no limit to the prices a reckless and profligate court was willing to pay for luxurious beauty during the sumptuous, extravagant reign of Louis the Magnificent of France. For much that was most splendid and beautiful in furniture making at this period stands the name of Charles André Boulle. His imagination and skill were given full play, and he proved equal to the demands made upon him.Boulle was a remarkable man. In a court whose only thought was of pleasure and display, he realized that his furniture must not only excel all others in richness, beauty, and cost; it must also be both comfortable and useful. He was appointed cabinet maker to the Dauphin, the heir to the throne of France. This distinction, together with his own tastes, led him to copy some of the manners and bearing of his rich customers.' He was an aristocrat among furniture makers. He spent the greater part of his large fortune in filling his workshop with works of art. His warehouses were packed with precious woods and finished and unfinished pieces of magnificent furniture. In his own rooms were priceless works of art, the collection of a lifetime—gems, medals, drawings, and paintings, which included forty-eight drawings by Raphael''.

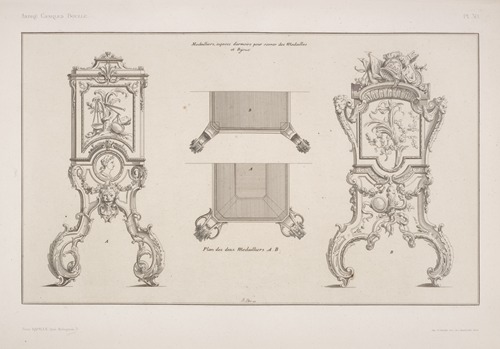

Boulle's output from, at one time, three workshops included commodes, bureaux, armoires, pedestals, clockcases and lighting-fixtures, richly mounted with gilt-bronze that he modelled himself. Despite his skills, his exquisite craftsmen and the high prices he commanded, Boulle was always running out of money. This was mostly as a direct result of his lifelong obsession as a collector and hoarder of works of art. Although he undoubtedly drew inspiration for his own works from these purchases, it meant he did not always pay his workmen regularly. In addition, clients who had made considerable advances failed to obtain the pieces they had ordered and, on more than one occasion. These dissatisfied clients made formal attempts to get Royal permission to arrest him for his debts, despite the Royal protection afforded by his post at the Louvre. In 1704, the king granted him six months' protection from his creditors on condition that Boulle use the time to regulate his affairs or this would be the last grace that His Majesty would do him. Living beyond his means seems to have been a family trait as history repeated itself, twenty years later, when one of his sons was arrested at Fontainebleau and actually imprisoned until King Louis XV had him released.

In 1720, Boulle's shaky finances were dealt a further blow by a fire which began in an adjoining atelier and spread to his workshop in the Place du Louvre (one of three he maintained), completely destroying twenty workbenches and the various tools of eighteen ébénistes, two menuisiers as well as most of the precious seasoned wood, appliances, models, and finished works of art. What could be salvaged was sold and a petition for financial assistance made to the Regent, the success of this appeal is unknown. According to Boulle's friend, Pierre-Jean Mariette, many of his pecuniary problems were indeed as a direct result of his obsession for collecting and hoarding pictures, engravings, and other art objects. The inventory of his losses in this fire exceeded 40,000 livres, included many old Masters, not to mention 48 drawings by Raphael, wax models by Michelangelo and the manuscript journal kept by Rubens in Italy.

The compulsive Boulle attended literally every sale of drawings and engravings he could. He borrowed at high interest rates to pay for his purchases until the next auction when he devised other means to gain more cash. His friend Pierre-Jean Mariette informs that it was a compulsion that was impossible to cure. André-Charles Boulle died on 29 February 1732 in the Louvre, leaving many debts for his four sons to deal with and, to whom he had transferred ownership of his business and tenure in the Louvre some seventeen years earlier.