John R. Grabach was an American painter who gained prominence in the art world of the 1920s and 1930s. He was known for his gritty, social realism works depicting urban working-class scenes of New York City and New Jersey. Although his work resembles that of the Ashcan school, he is generally considered a post-Ashcan, urban realist. Characterized as the “leading American painter of the Great Depression” and “a dynamic painter with a strong spirit of nationalism,” his career spanned most of the 20th century. Grabach also authored the art text, How to Draw the Human Figure, first published in 1957.

John Robert Grabach was born March 2, 1886, in Newark, New Jersey (see note below). His father, also named John Grabach, was a jeweler, and his mother, Genoveva (Eva), a homemaker and, later, a dressmaker. He was an only child. At the age of 10, he showed an affinity towards drawing, carefully copying illustrations from books.

Grabach’s first serious art training began at an early age with Albert Dick in Newark. By age 14, he was studying in Orange, New Jersey with August Schwabe, who taking a personal interest in his student, introduced Grabach to the Newark Sketch Club. In 1904, at age 18, Grabach took employment with a silverware manufacturer, where he first worked as a machinist and later as a designer. With his interest in art unabated, Grabach continued to paint and draw in his spare time, and he enrolled at the Art Students League of New York where, commuting from New Jersey, he took night classes, studying with Kenyon Cox, Frank V. DuMond, and George Bridgman.

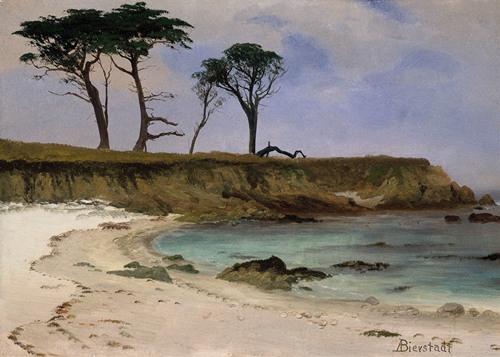

In 1912, Grabach, now in his mid-20s, moved from Newark to rural Greenfield, Massachusetts, where he resided for three years. Although he continued to work as a silverware designer — for the firm Rogers, Lunt and Bowlen — his primary interest became his art. During this time, he painted — in a style not unlike that of John Twachtman’s — several impressionistic winter landscapes of the Connecticut River and New England countryside. His Banks of the Connecticut River, shown at the National Academy’s 1914 Winter Exhibition, was selected for inclusion in the 1915 Panama-Pacific International Exhibition in San Francisco, a singular honor for a generally unknown artist.

Returning to New Jersey in 1915, Grabach aggressively strove to increase his visibility in art circles by exhibiting widely. In close touch with artists active in New York City, he developed an affinity for the Ashcan artists’ street scenes and was particularly intrigued by the work of John Sloan and George Bellows. During his daily trips into the city, he became fascinated with the “washdays” of Tuesdays when tenement apartment dwellers strung their laundry on lines from buildings and trees. It was in these wash-day scenes where Grabach found a theme that satisfied his artistic expectations. Notable works of this period, which encompass aspects of Americanism, social relevance, contemporariness, and visual stimulation, include the paintings Wash Day in Spring (1921) and East Side, New York (1924).

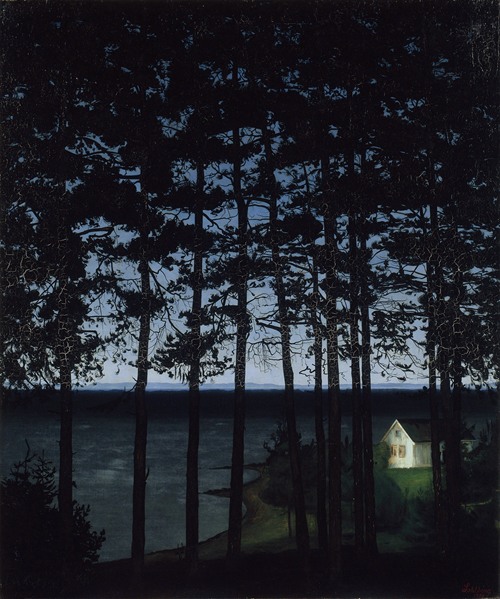

In the 1920s, the painting of urban landscapes engrossed Grabach, and he took a studio in Brooklyn near the Brooklyn Bridge. It was around this time his work began to garner increasing attention. In 1924, he was the recipient of the Art Institute of Chicago’s Peabody Prize. As the 1920s waned and the Great Depression unfolded, Grabach’s breezy, decorative urban scenes began to evolve. Increasingly concerned by social conditions, his paintings became more melancholy and political, often featuring a somber palette of grays, dark greens, browns, black, and muted reds. The paintings The Lone House (1929), The Fifth Year (1934) and The Horizon (Arising) (1935) exemplify this directional shift toward the more serious and personal. The brightness and festivity of his early work was no longer, replaced by themes of cynicism and human anonymity. In 1928, the Art Institute of Chicago hosted a solo exhibition of his work.

In 1939, his horse race painting, Taking the Hurdles (c. 1938), was accepted for display at the IBM pavilion at the World Fair in New York. Later purchased by the IBM Corporation, the work showed none of the high spirits of a horse racing event, but rather a deep disconnect between the race and disinterested spectators. (Grabach, at a later date, bought the painting back and sold it to a private collector.) As American art and artists turned again to Europe for inspiration in abstract expressionism and surrealism, Grabach became disillusioned with the contemporary art scene. Becoming more insular he turned to the Munich School of the nineteenth century for inspiration, drifting away from the art circles of New York and elsewhere. He exhibited less and taught more.

Grabach was honored in 1953 with a solo show at The Grand Central Galleries in New York City. In 1957, his book, How to Draw the Human Figure, was published. In 1961, he was elected an Associate of the National Academy of Design, a recognition he earlier had declined. With this accolade, he began to exhibit more often. He was elected full Academician of the National Academy of Design in 1968. Throughout the 1960s and 1970s he continued to paint and teach, though his works were more often small character studies in oil, rather than large exhibition paintings. In 1980, he was honored with a one-artist exhibition at The Smithsonian American Art Museum.

Due to the financial hardships of the Great Depression, Grabach accepted in 1932 a position teaching life-drawing classing at the Newark School of Fine and Industrial Art. During this time, he also worked as a free-lance illustrator. Grabach taught at the Newark School and other nearby educational institutions for several decades. Among his many thousands of students was Henry Gasser, who became a popular Newark artist as well as Grabach's longtime friend and confidant.

Grabach was by all accounts an only child. He was 10 when his father died, on August 21, 1896, at age 30, in Newark. At age 25, Grabach married Anna Thompson October 21, 1911, in Newark. The couple were captured in the 1920 census living at 915 Sanford Street in Newark. The marriage, which produced no children, ended when Anna died March 28, 1925. Grabach never remarried. In the 1930 census, he is listed living with his mother, Eva, at 915 Sanford Street. She died sometime between 1930 and 1940. Grabach continued to live at 915 Sanford Street until his death in 1981.

Grabach died March 17, 1981, at age 95, in Newark. He died in "almost total obscurity."

You may also like