Charles Percier was a neoclassical French architect, interior decorator and designer, who worked in a close partnership with Pierre François Léonard Fontaine, originally his friend from student days. For work undertaken from 1794 onward, trying to ascribe conceptions or details to one or other of them is fruitless; it is impossible to disentangle their cooperative efforts in this fashion. Together, Percier and Fontaine were inventors and major proponents of the rich, grand, consciously-archaeological versions of neoclassicism we recognise as Directoire style and Empire style.

Following Charles Percier's death in 1838, Fontaine designed a tomb in their characteristic style in the Pere Lachaise Cemetery. Percier and Fontaine had lived together as well as being colleagues. Fontaine married late in life and after his death in 1853 his body was placed in the same tomb according to his wishes.

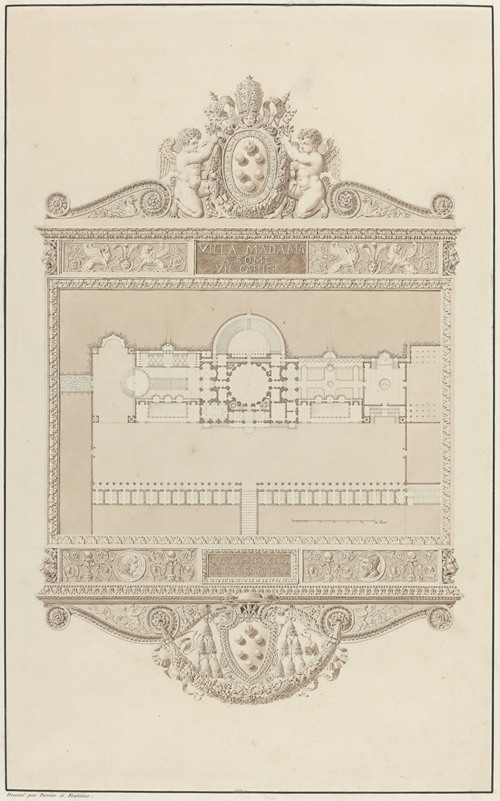

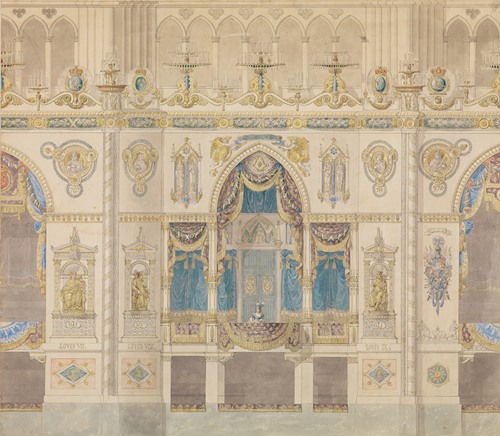

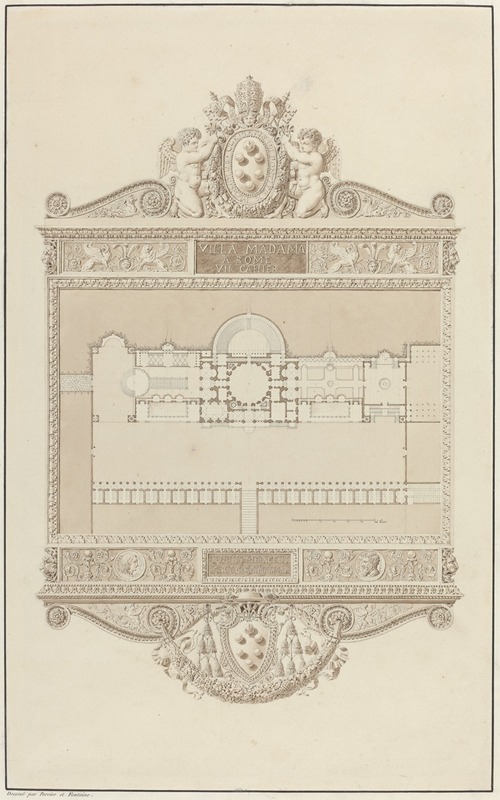

Percier was born at Paris in 1764. In 1784, at age nineteen, he won the Prix de Rome, a government-funded fellowship for study in Rome. There he met Fontaine. One early product of their collaboration was Palais, maisons et autres édifices modernes dessinés à Rome ("A palace, houses and other modern buildings designed in Rome"), which attracted the attention of prospective clients when they returned to Paris. At the end of 1792, near the end of the first phase of the French Revolution, Percier was appointed to supervise the scenery at the Paris Opéra, a post at the center of innovative design. Fontaine returned from the security of London, where he had been exiled, and they continued at the Opéra together until 1796. Claude-Louis Bernier (born 9 October 1755 died 10 January 1830, Paris) was a third member of their team.

Napoleon Bonaparte liked their work. The calculated theater of the Empire style, its aggressive opulence restrained by a slightly dry and correct sense of the antique taste, and its neo-Roman values, imperial yet separate from the ancien régime, appealed to the future emperor. He appointed them his personal architects and never wavered in his decision; they were at work on imperial projects almost until the very end of Napoleon's time in power. The relationship only dissolved when Napoleon retired to Elba. After the restoration of the House of Bourbon in 1814, they found themselves associated too intimately with the Empire ever to earn an official commission again. From that time forward, Percier conducted a student atelier, a teaching studio or workshop. One of Percier's pupils, Auguste de Montferrand, designed Saint Isaac's Cathedral in St Petersburg for Tsar Alexander I.

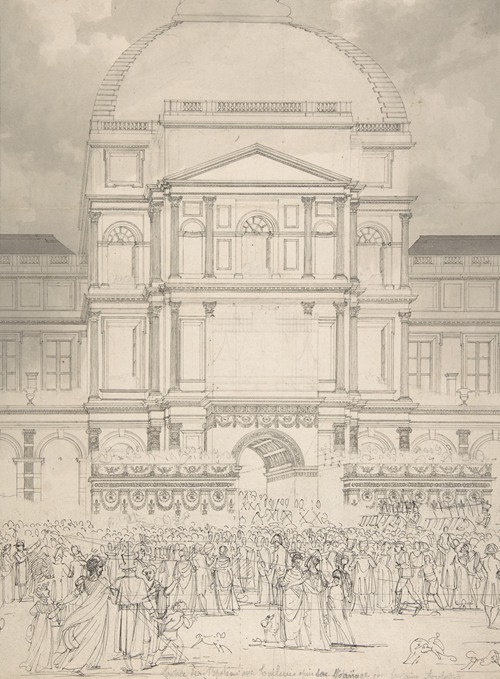

They worked for ten years (1802–1812) on the Louvre. The old palace had not been a royal residence for generations, so it was free of any taint associated with the detested Bourbons. It stood in the heart of Paris, so that the vain Emperor could be seen coming and going, unlike Versailles, which, besides, had been rendered uninhabitable through destruction and looting.

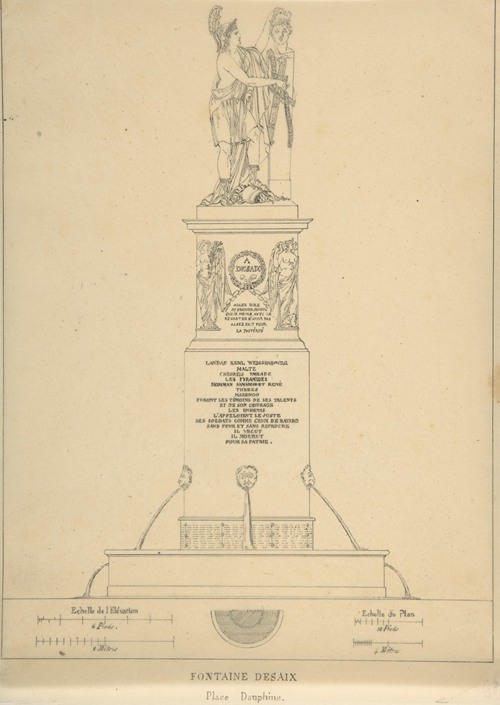

They worked on the Tuileries Palace that faced the Louvre across the Place du Carrousel and the parterres. In that prominent square, Percier and Fontaine designed the Arc du Carrousel (1807–1808), commemorating the Battle of Austerlitz,

They also worked at Josephine's Château de Malmaison, at the Château de Montgobert for Pauline Bonaparte, and did alterations and decorations for former Bourbon palaces or castles at Compiègne, Saint-Cloud, and Fontainebleau.

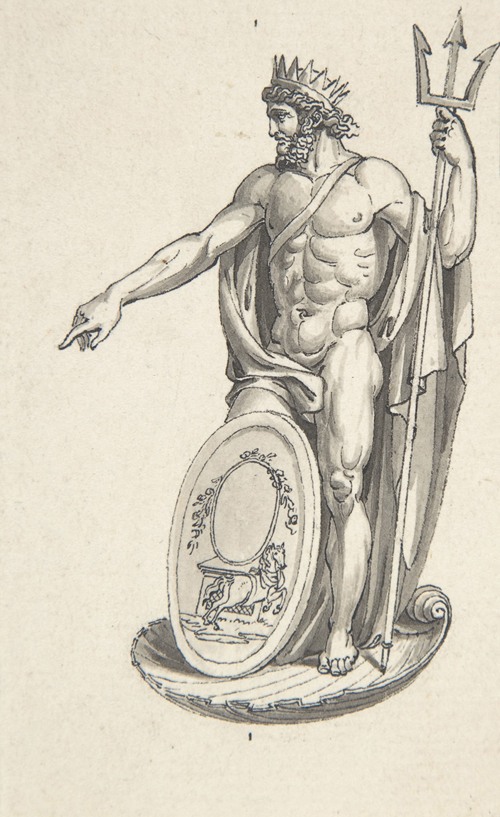

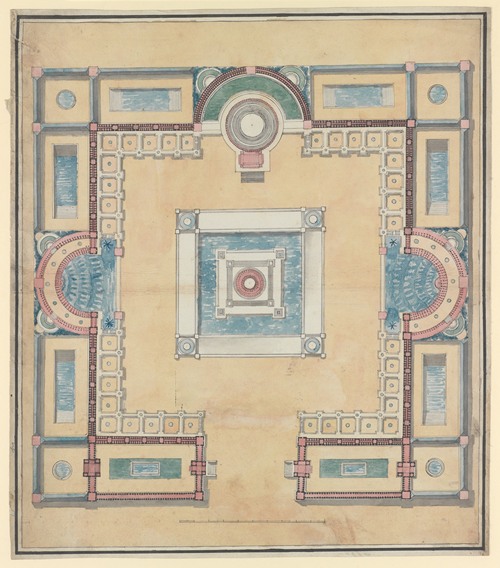

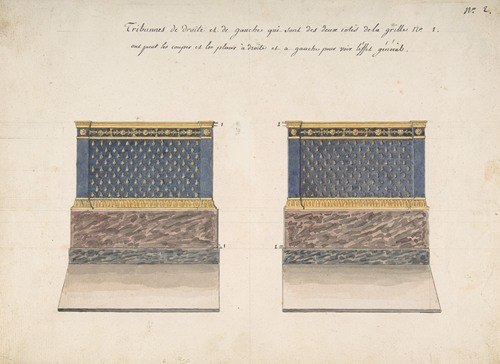

Percier and Fontaine designed every detail in their interiors: state beds, sculptural side tables, and other furniture, wall lights and candlesticks, chandeliers, door hardware, textiles, and wallpaper. On special occasions, Percier was called upon to design for the Sèvres porcelain manufactory: in 1814 Percier's published designs were adapted by Alexandre Brogniart, director of Sèvres, a grand classicising vase 137 cm tall, that came to be known as the "Londonderry Vase" when Louis XVIII gave it to the Marquess of Londonderry just before the Congress of Vienna. Percier and Fontaine published several later books, notably Recueil de décoration intérieure concernant tout ce qui rapporte à l'ameublement ("Collection of interior designs: Everything that relates to furniture", 1812) with its engravings in a spare outline technique. These engravings spread their style beyond the Empire; they helped put a French stamp on the English Regency style and influenced the Dutch-British connoisseur-designer, Thomas Hope (1769–1831).