Andrea Sacchi was an Italian painter of High Baroque Classicism, active in Rome. A generation of artists who shared his style of art include the painters Nicolas Poussin and Giovanni Battista Passeri, the sculptors Alessandro Algardi and François Duquesnoy, and the contemporary biographer Giovanni Bellori.

Sacchi was born in Rome. His father, Benedetto, was an undistinguished painter. According to the biographer Giovanni Pietro Bellori (who was also a great friend of Sacchi's), Andrea initially entered the studio of Cavalier d'Arpino.

Sacchi later entered Francesco Albani's workshop and spent most of his time in Rome where he eventually died. Much of his early career was helped by the regular patronage by Cardinal Antonio Barberini, who commissioned art for the Capuchin church in Rome and the Palazzo Barberini.

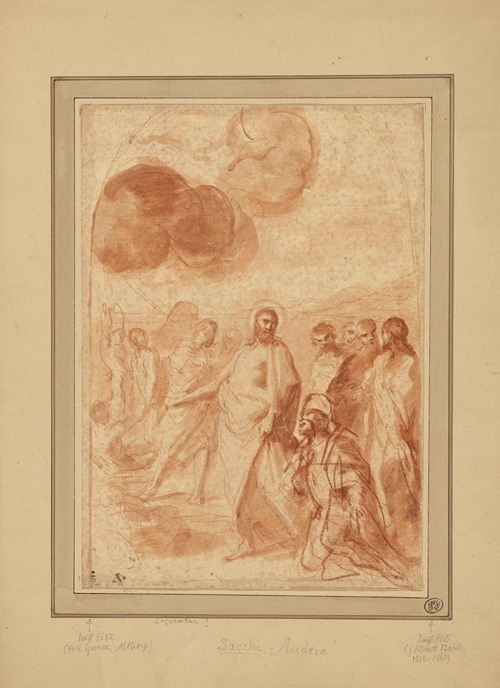

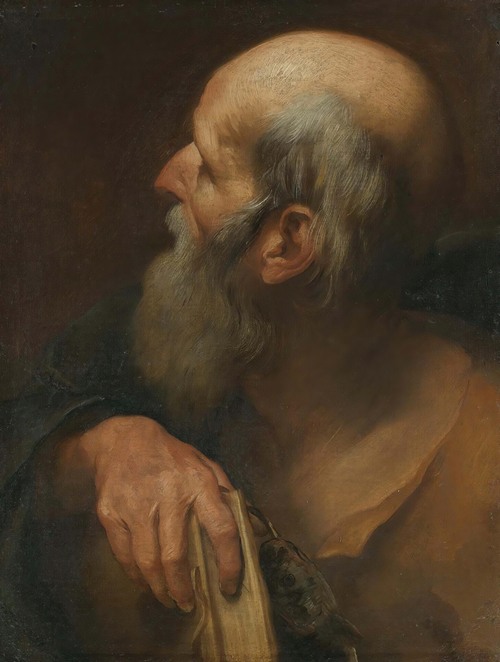

A contemporary rival of Pietro da Cortona, Sacchi studied the paintings of Raphael and the influence of Raphael is apparent in a number of his works, particularly with reference to the use of few figures and their expressions. He reputedly travelled to Venice and Parma and studied the works of Correggio.

Two of his major works on canvas are altarpieces now displayed in the Pinacoteca Vaticana, the painting gallery in the Vatican (see Main works below).

As a young man, Sacchi had worked under Cortona at the Villa Sacchetti at Castelfusano (1627–1629). But in a set of public debates at the Accademia di San Luca, the guild for artists in Rome, he strongly criticized Cortona's exuberance. The debate is significant because it indicates how two of the leading proponents of the prevailing styles in painting, now called 'Classical' and 'Baroque', discussed the differences between their work.

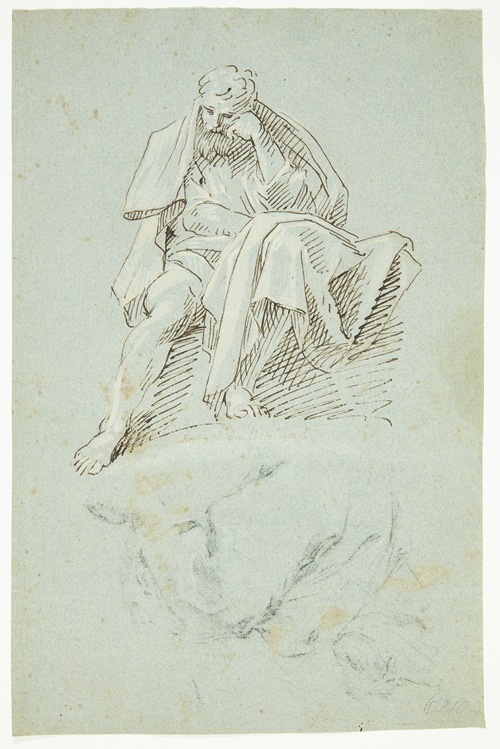

In particular, Sacchi advocated that since a unique, individual expression, gesture and movement needed to be assigned to each figure in a composition, so a painting should only have a few figures. In a crowded composition, the figures would be deprived of individuality, and thus cloud the particular meaning of the piece. In some ways this was a reaction against the zealous excess of crowds in paintings by artists such as Zuccari in the previous generation, and by Cortona among his contemporaries. Simplicity and unity were essential to Sacchi who, drawing an analogy to poetry, likened painting to tragedy. In his counter-argument, Cortona made the case that large paintings with many figures were like an epic which could develop multiple sub-themes. But for Sacchi, the encrustation of a painting with excess decorative details, including melees of crowds, would represent something akin to 'wall-paper' art rather than focused narrative. Among the partisans of Sacchi's argument for simplicity and focus were his friends, the sculptor Algardi and painter Poussin. The controversy was however less pitched and monolithic than some might suggest. In fact, Poussin's biographer Bellori recounts that the artist 'used to laugh at those who contract for a [history painting] with six or eight figures or some other fixed number.'

Sacchi and Albani, among others, shared dissatisfaction with the artistic depiction of low or genre subjects and themes, such as those preferred by the Bamboccianti and even the Caravaggisti. They felt that high art should focus on exalted themes- biblical, mythological, or from classical ancient history.

Sacchi, who worked almost always in Rome, left few pictures visible in private galleries. He had a flourishing school: Carlo Maratta was a younger collaborator or pupil. In Maratta's large studio, Sacchi's preference for a grand manner style would find pre-eminence among Roman circles for decades to follow. But many others worked under him or his influence including Francesco Fiorelli, Luigi Garzi, Francesco Lauri, Andrea Camassei, and Giacinto Gimignani. Sacchi's own illegitimate son Giuseppe, died young after high hopes for his future.

Sacchi died at Nettuno in 1661.