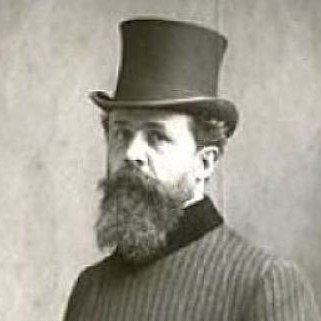

Henri Gustave Jossot was a French cartoonist, caricaturist, painter, poster artist, and libertarian writer.

As a child, Henri Gustave Jossot did not seem predisposed to a career as a satirist. His rebellious nature led him to regularly defy authority, whether paternal or academic. His widowed father remarried a woman whom Henri Gustave Jossot did not like, and pushed him to become a naval officer. He protested, had a child with the family's laundress, and married her after his father's death. After the death of his mother and then his father, his daughter also died of meningitis. Deeply affected, he immersed himself even more in his passion, drawing.

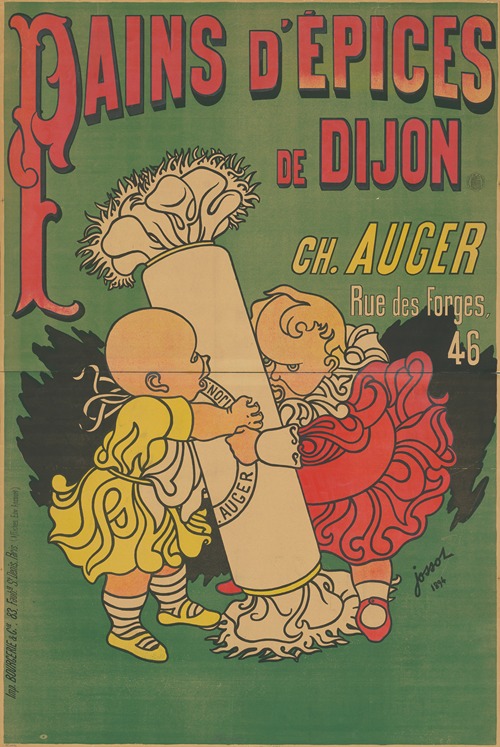

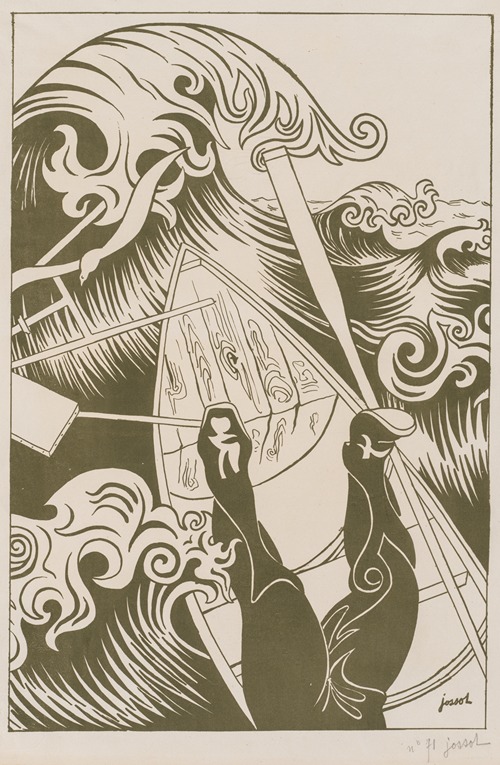

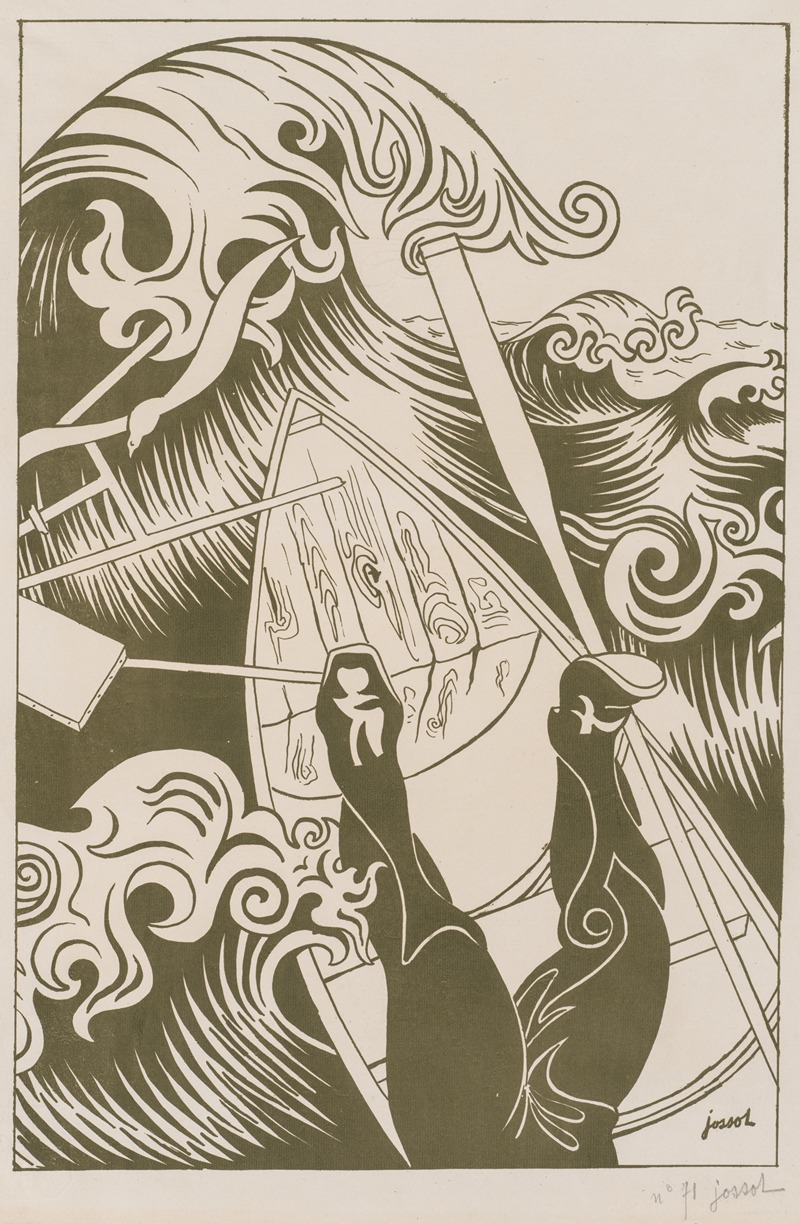

Jossot began his career as a press cartoonist in 1886 in the local press. Unlike Jules Grandjouan, he was not a politically engaged cartoonist. His career took him to Paris, where he frequented the Symbolist artists of Pont-Aven, among others. At that time, in the early 1890s, Paris was caught between the aftermath of the Boulangist crisis and the Panama scandal (1893), which was just beginning, making the French capital the center of caricature. From his early days in caricature, he found his style in arabesques in the Art Nouveau tradition, which could also be likened to the Nabis, with large areas of color reminiscent of Japanese art, plus a touch of parody. His style is therefore particularly recognizable. Jossot began his career as a press cartoonist around 1892 as a humorist who was still widely accepted in La Caricature and La Butte.

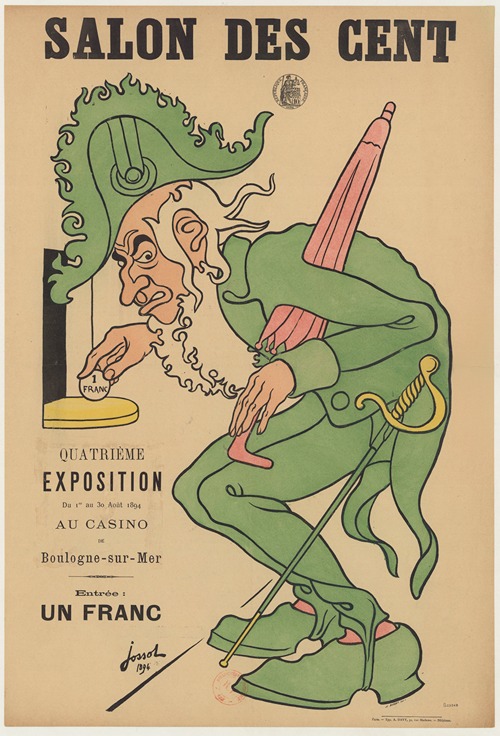

In 1894, Jossot presented watercolor caricatures at the Salon des Indépendants, which caught the eye of Léon Maillard, editor of the magazine La Plume, then considered “a veritable machine for legitimizing young talent.” This allowed him to exhibit his work more widely, including at the Salon des Cent (1894, 1895), the Salon de la Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts (1895), the Salon d'Automne (1908, 1909, 1911) and the Salon des Indépendants (1894, 1896, 1910, 1911, 1921). Léon Maillard said of him that “the arabesques of his lines are the rhythmic waves of movement, vibrating for the poor dispossessed.” Jossot realized the potential of using the aesthetics of distortion to achieve a subversive and politically engaged effect. He also contributed to La Critique.

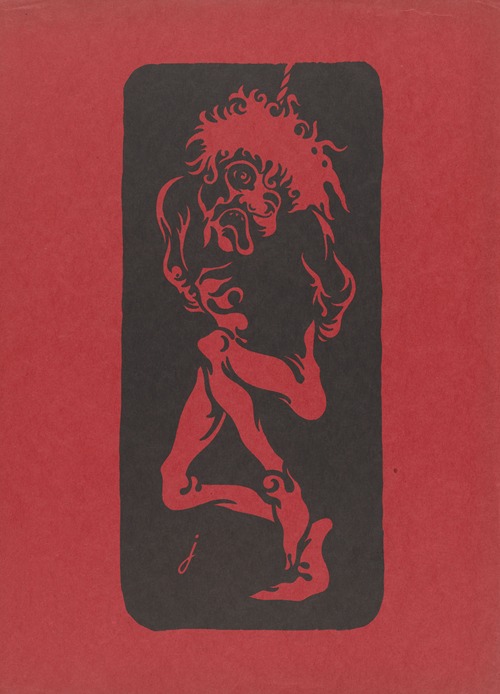

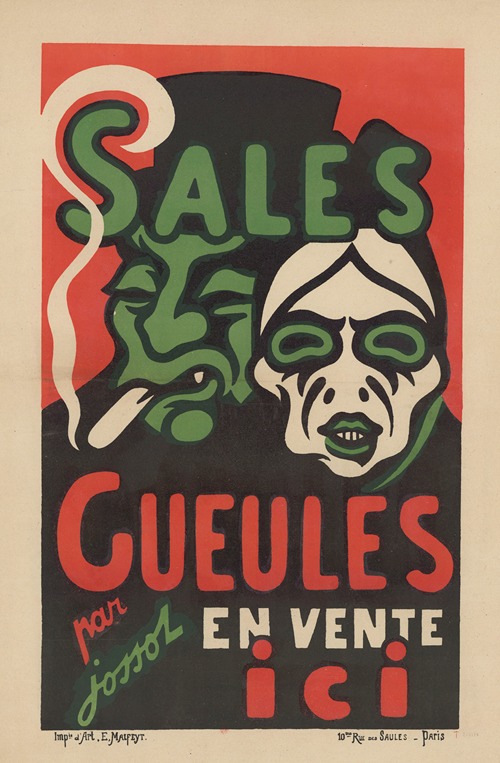

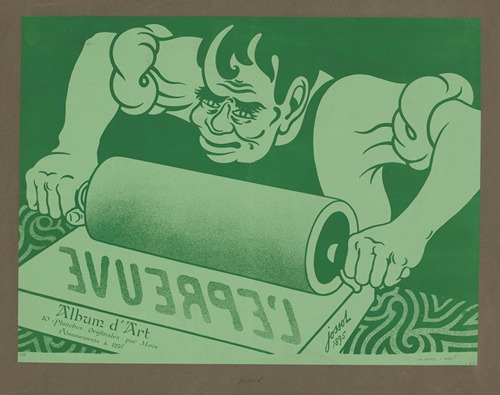

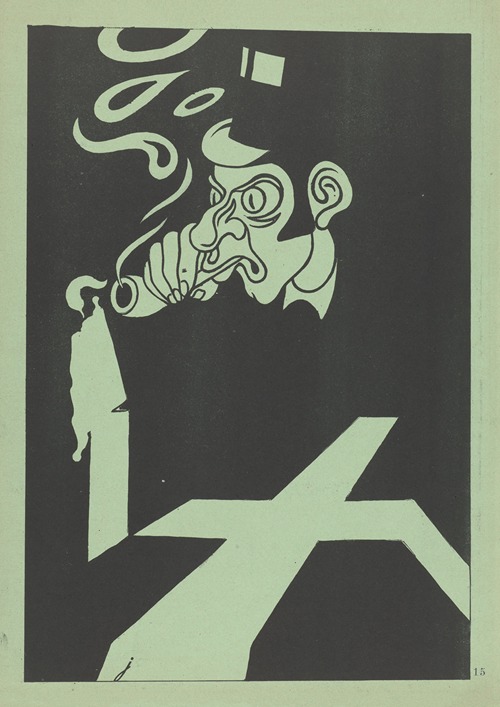

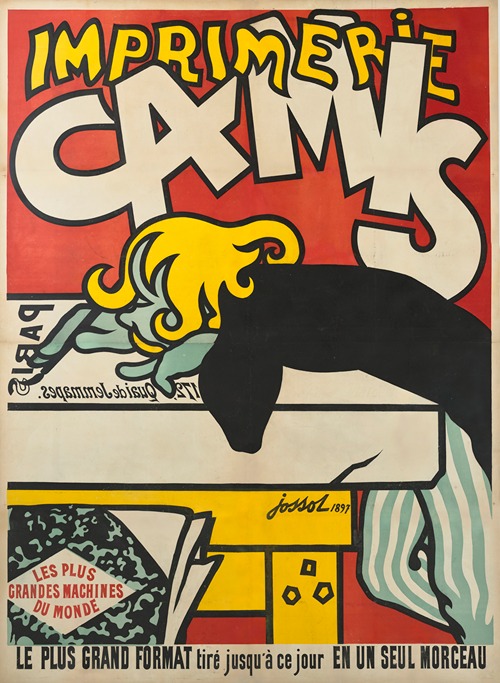

Between 1897 and 1899, Jossot joined Camis as a poster artist before setting up his own studio. When L'Assiette au beurre was launched, a veritable revolution in the press and press cartooning, Jossot was one of the first cartoonists to share the same targets: the bosses, the bourgeoisie, the army, the government, colonization, religion, morals, etc. His style changed: his lines became thicker, the captions minimal, the simplification maximal, and masks in the style of ukiyo-e became characteristic. He used single colors or flat reds that caught the eye. Jossot became a reference point, and remains so today among connoisseurs. He published 300 drawings in L'Assiette au beurre between 1901 and 1907. He published numerous drawings on the separation of church and state. His most famous press cartoon, published in 1902 in a special issue of L'Assiette au beurre devoted to the political influence of Catholic orders, shows priests marching in goose step, suggesting a connection between conformity and religiosity. Caricature played a major role in the struggle to establish secularism in France.

In 1911, after traveling to Tunisia, a country he fell in love with, he settled there permanently and, abandoning his caricature career altogether, painted landscapes and scenes of everyday life in an Orientalist style. At the same time, his artist friends went into exile (Grandjouan) or died (Aristide Delannoy) and L'Assiette au beurre disappeared. After reconnecting with Catholicism, Jossot converted to Islam in 1913. He then took the name “Abdul Karim Jossot.” A pacifist, he stopped drawing during the war and even gave up painting. In 1923, he followed Sheikh Ahmad al-Alawi on the path of Sufism. He wrote Le Sentier d'Allah (The Path of Allah) in 1927, but eventually distanced himself from Islam, renounced his Muslim name, and abandoned his Arab clothing.

In 1951, in his unpublished memoirs Goutte à goutte (Drop by Drop), he proclaimed his rediscovered atheism and died in poverty the same year.

In 2011, the city of Paris dedicated an exhibition to him at the Forney Library.