Jan or Johannes Swammerdam was a Dutch biologist and microscopist. His work on insects demonstrated that the various phases during the life of an insect—egg, larva, pupa, and adult—are different forms of the same animal. As part of his anatomical research, he carried out experiments on muscle contraction. In 1658, he was the first to observe and describe red blood cells. He was one of the first people to use the microscope in dissections, and his techniques remained useful for hundreds of years.

Johannes Swammerdam was baptized on 15 February 1637 in the Oude Kerk Amsterdam. His father Jan (or Johannes) Jacobsz (-1678) was an apothecary and an amateur collector of minerals, coins, fossils, and insects from around the world. In 1632 he married Baartje Jans (-1660) in Weesp. The couple lived across the Montelbaanstoren, near the harbour, the headquarter and the warehouses of the Dutch West India Company where an uncle worked. Some of their children were buried in the Walloon church, likewise Jan himself (who never married) and his father.

As a youngster, Swammerdam had helped his father to take care of his curiosity collection. Despite his father's wish that he should study theology Swammerdam started to study medicine in 1661 at the University of Leiden. He studied under the guidance of Johannes van Horne and Franciscus Sylvius. Among his fellow students were Frederik Ruysch, Reinier de Graaf, Ole Borch, Theodor Kerckring, Steven Blankaart, Burchard de Volder, Ehrenfried Walther von Tschirnhaus and Niels Stensen. While studying medicine Swammerdam started his own collection of insects.

In 1663 Swammerdam moved to France to continue his studies. It seems together with Steno. He studied for one year at the Protestant University of Saumur, under the guidance of Tanaquil Faber. Subsequently, he studied in Paris at the scientific academy of Melchisédech Thévenot. 1665 he returned to the Dutch Republic and joined a group of physicians who performed dissections and published their findings. Between 1666 and 1667 Swammerdam concluded his study of medicine at the University of Leiden; he received his doctorate in medicine in 1667 under van Horne for his dissertation on the mechanism of respiration, published under the title De respiratione usuque pulmonum.

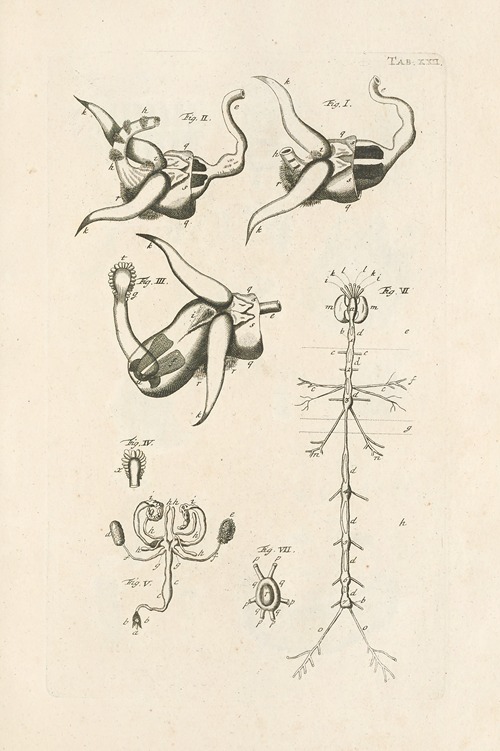

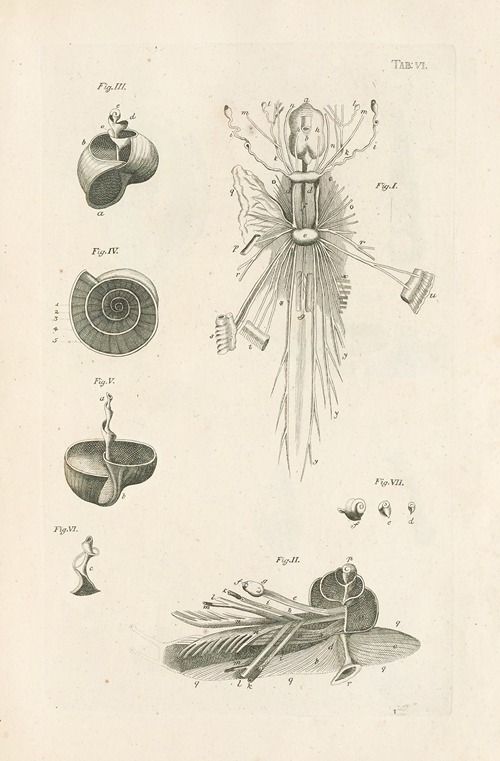

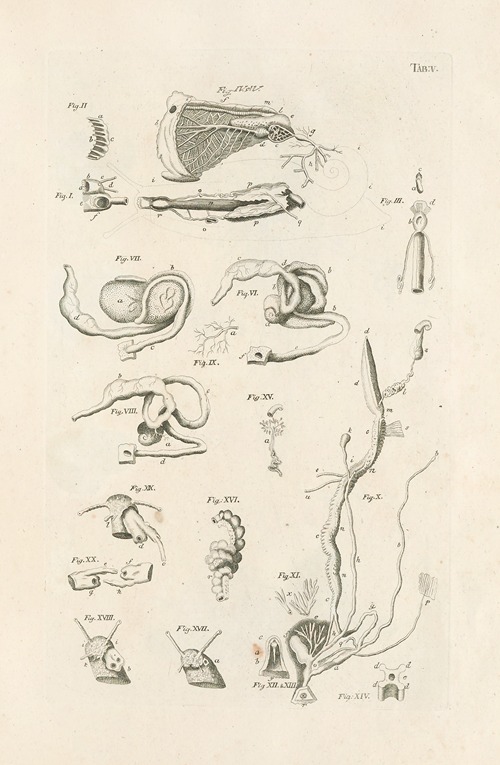

Together with van Horne, he researched the anatomy of the uterus. The result of this research was published under the title Miraculum naturae sive uteri muliebris fabrica in 1672. Swammerdam accused Reinier de Graaf of taking credit of discoveries he and Van Horne had made earlier regarding the importance of the ovary and its eggs. He used waxen injection techniques and a single-lens microscope made by Johannes Hudde.

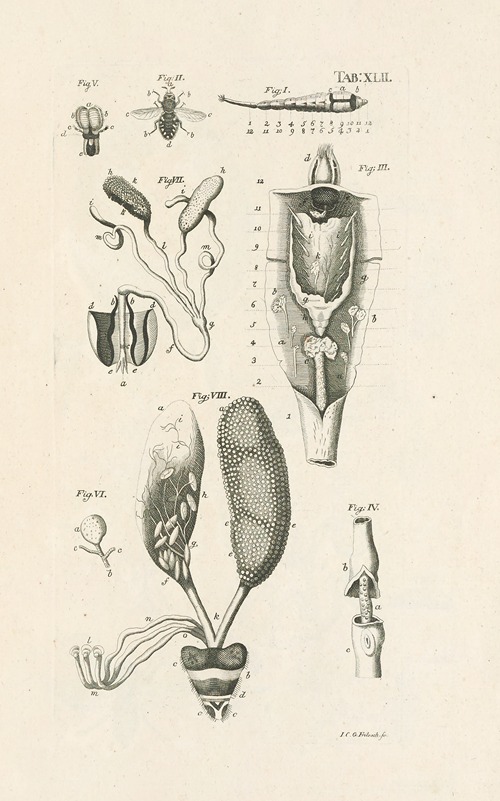

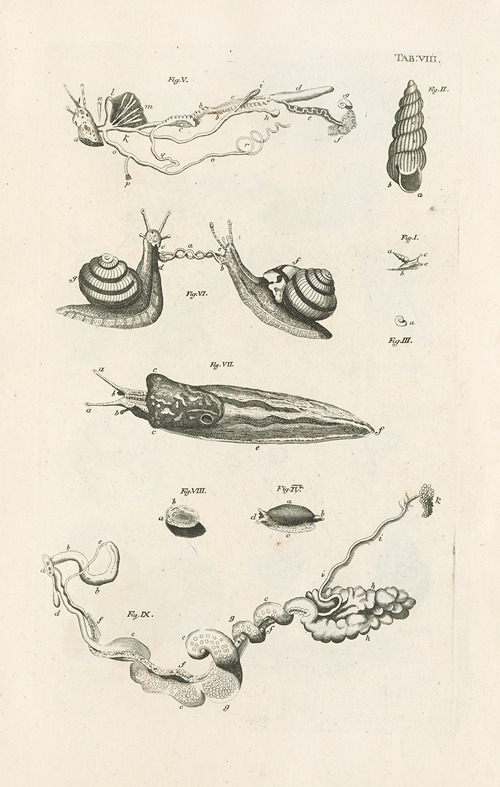

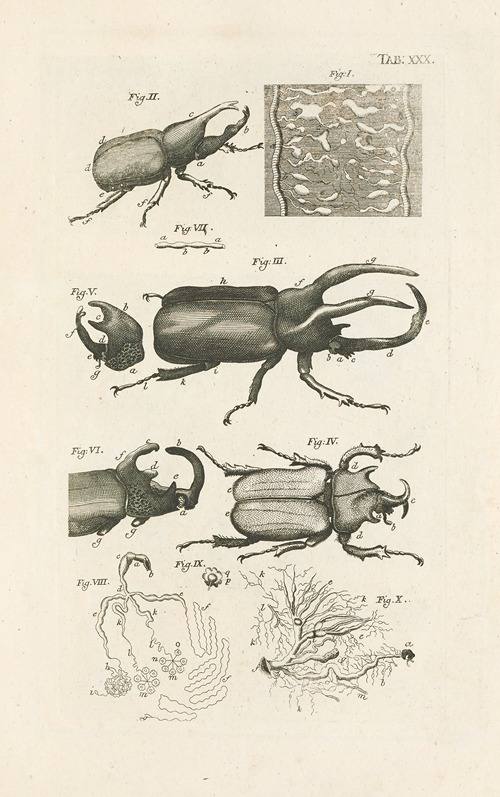

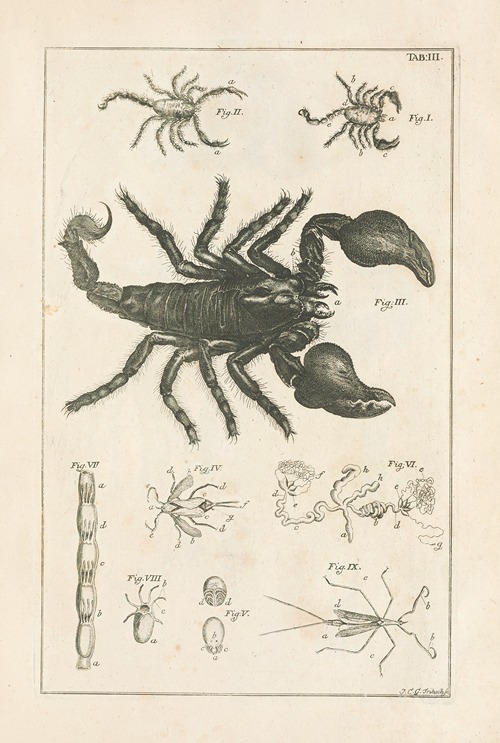

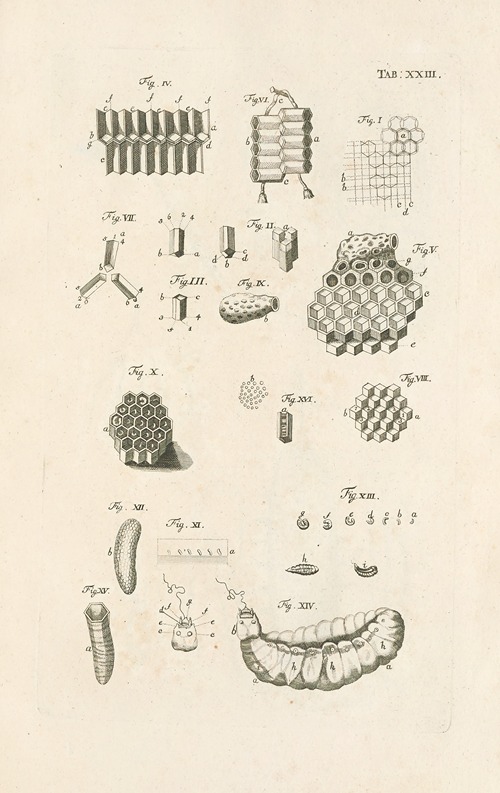

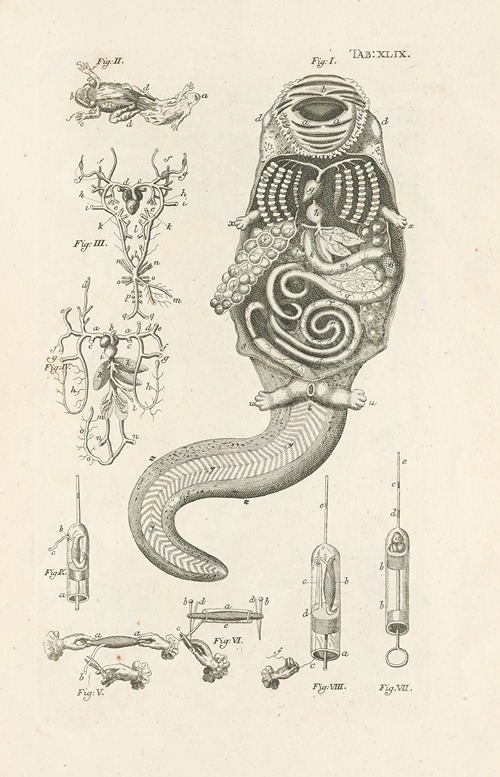

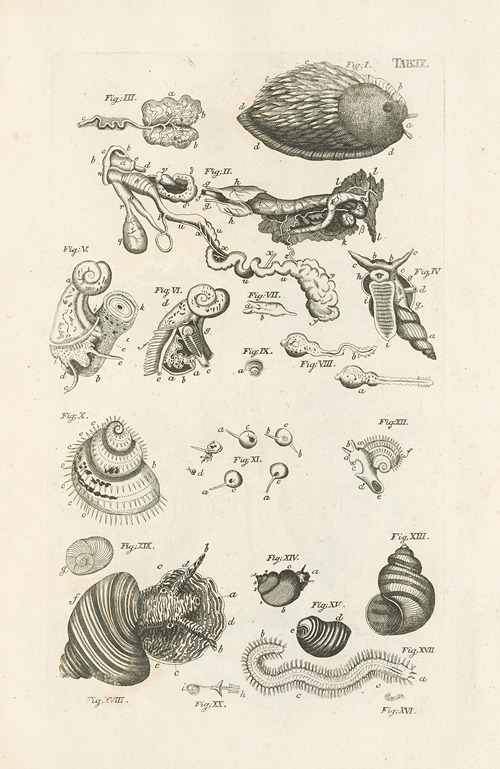

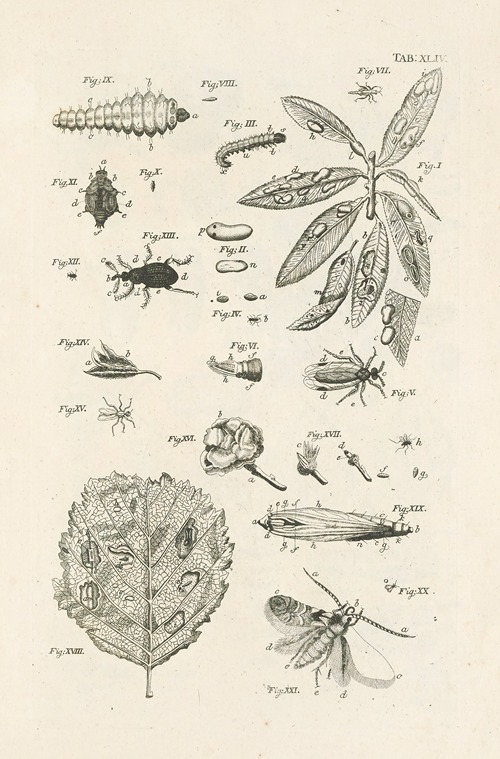

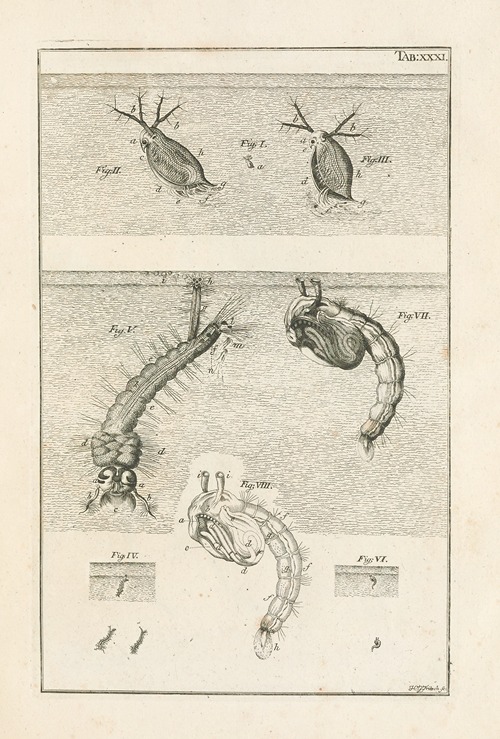

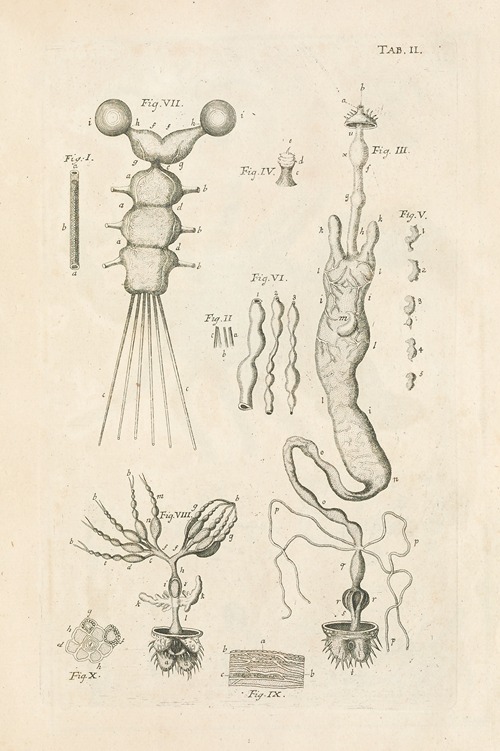

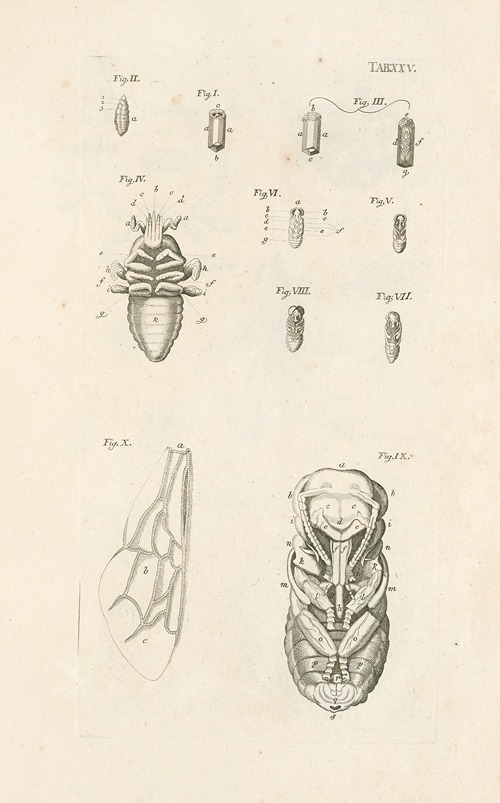

While studying medicine Swammerdam had started to dissect insects and after qualifying as a doctor, he focused on them. His father pressured him to earn a living, but Swammerdam persevered and in late 1669 published Historia insectorum generalis ofte Algemeene verhandeling van de bloedeloose dierkens (The General History of Insects, or General Treatise on little Bloodless Animals). The treatise summarised his study of insects he had collected in France and around Amsterdam. He countered the prevailing Aristotelian notion that insects were imperfect animals that lacked internal anatomy. Following the publication his father withdrew all financial support. As a result, Swammerdam was forced, at least occasionally, to practice medicine in order to finance his own research. He obtained leave at Amsterdam to dissect the bodies of those who died in the hospital.

At university Swammerdam engaged deeply in the religious and philosophical ideas of his time. He categorically opposed the ideas behind spontaneous generation, which held that God had created some creatures, but not insects. Swammerdam argued that this would blasphemously imply that parts of the universe were excluded from God's will. In his scientific study, Swammerdam tried to prove that God's creation happened time after time, and that it was uniform and stable. Swammerdam was much influenced by René Descartes, whose natural philosophy had been widely adopted by Dutch intellectuals. In Discours de la Methode Descartes had argued that nature was orderly and obeyed fixed laws, thus nature could be explained rationally.

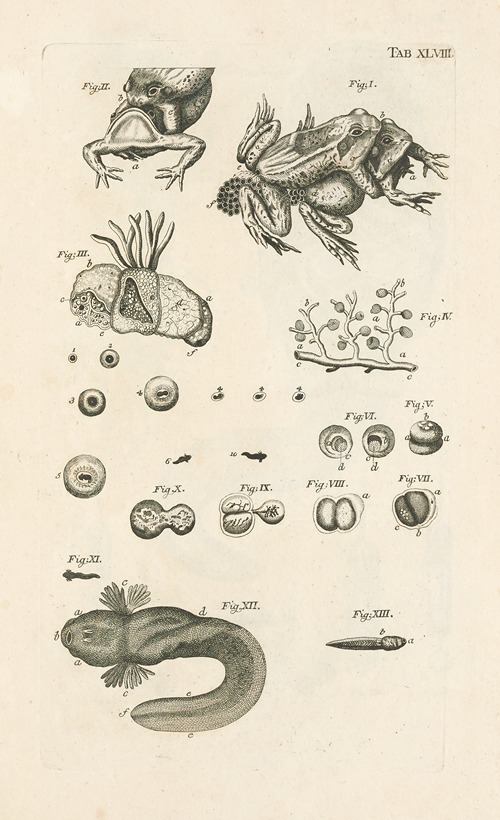

Swammerdam was convinced that the creation, or generation, of all creatures obeyed the same laws. Having studied the reproductive organs of men and women at university he set out to study the generation of insects. He had devoted himself to studying insects after discovering that the king bee was indeed a queen bee. Swammerdam knew this because he had found eggs inside the creature. But he did not publish this finding. Swammerdam corresponded with Matthew Slade and Paolo Boccone and was visited by Willem Piso, Nicolaas Tulp and Nicolaas Witsen. He showed Cosimo III de' Medici, accompanied by Thévenot, another revolutionary discovery. Inside a caterpillar the limbs and wings of the butterfly could be seen (now called the imaginal discs).

When Swammerdam published The General History of Insects, or General Treatise on little Bloodless Animals later that year he not only did away with the idea that insects lacked internal anatomy but also attacked the Christian notion that insects originated from spontaneous generation and that their life cycle was a metamorphosis. Swammerdam maintained that all insects originated from eggs and their limbs grew and developed slowly. Thus there was no distinction between insects and so-called higher animals. Swammerdam declared war on "vulgar errors" and the symbolic interpretation of insects was, in his mind, incompatible with the power of God, the almighty architect. Swammerdam, therefore, dispelled the seventeenth-century notion of metamorphosis —the idea that different life stages of an insect (e.g. caterpillar and butterfly) represent different individuals or a sudden change from one type of animal to another.

Together with his father he collected 6,000 objects in 27 drawer cabinets. Swammerdam's Historia insectorum generalis was widely known and applauded before he died. Two years after his death in 1680 it was translated into French and in 1685 it was translated into Latin. John Ray, author of the 1705 Historia insectorum, praised Swammerdam' methods, they were "the best of all". Though Swammerdam's work on insects and anatomy was significant, many current histories remember him as much for his methods and skill with microscopes as for his discoveries. He developed new techniques for examining, preserving, and dissecting specimens, including wax injection to make viewing blood vessels easier. A method he invented for the preparation of hollow human organs was later much employed in anatomy. He had corresponded with contemporaries across Europe and his friends Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz and Nicolas Malebranche used his microscopic research to substantiate their own natural and moral philosophy. But Swammerdam has also been credited with heralding the natural theology of the 18th century, were God's grand design was detected in the mechanics of the Solar System, the seasons, snowflakes and the anatomy of the human eye. An English translation of his entomological works by T. Floyd was published in 1758.