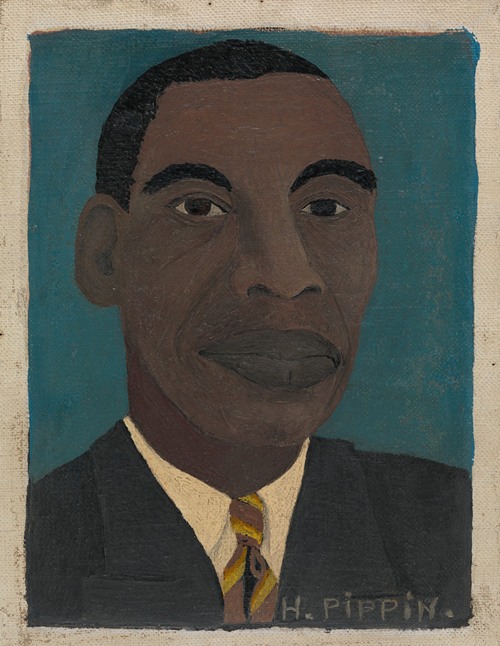

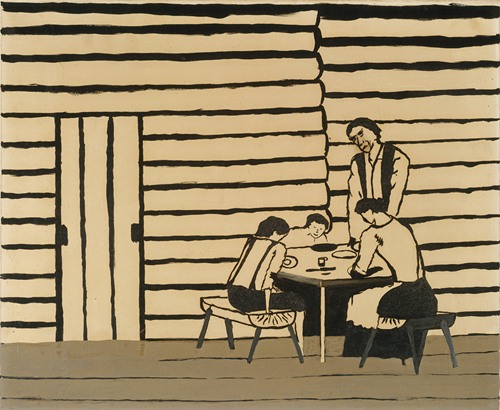

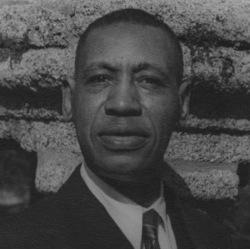

Horace Pippin was a self-taught American artist who painted a range of themes, including scenes inspired by his service in World War I, landscapes, portraits, and biblical subjects. Some of his best-known works address the U.S.'s history of slavery and racial segregation. He was the first Black artist to be the subject of a monograph, Selden Rodman's Horace Pippin, A Negro Painter in America (1947), and the New York Times eulogized him as the "most important Negro painter" in American history. He is buried at Chestnut Grove Annex Cemetery in West Goshen Township, Chester County, Pennsylvania. A Pennsylvania State historical Marker at 327 Gay Street, West Chester, Pennsylvania identifies his home at the time of his death and commemorates his accomplishments.

He was born in West Chester, Pennsylvania, on February 22, 1888, to Harriet Pippin; his father's identity is unknown. He grew up in and around Goshen, New York, but would return to West Chester in adulthood. In Goshen, he attended segregated schools until he was 15, when he went to work to support his ailing mother. As a boy, Horace responded to an art supply company's advertising contest and won his first set of crayons and a box of watercolors. As a youngster, Pippin made drawings of racehorses and jockeys from Goshen's celebrated racetrack. Prior to his service in World War I, Pippin worked as a hotel porter, a furniture packer, and an iron moulder. He was a member of St. John's African Union Methodist Protestant Church. In 1920, Pippin married Jennie Fetherstone Wade Giles, who had been widowed twice and had a six-year-old-son.

In World War I, Pippin served in K Company, the 3rd Battalion of the 369th infantry regiment, known for their bravery in battle as the famous Harlem Hellfighters. The predominately Black unit faced enormous racism, especially before they were transferred to the command of the French Army. They were the longest serving U.S. regiment on the war's frontlines, holding their ground against enemy fire almost continuously from mid-July until the end of the war. The regiment as a whole was awarded the French Croix de Guerre. In September 1918, Pippin was shot in the right shoulder by a German sniper. The injury initially cost him the use of his arm and always limited his range of motion. He was honorably discharged in 1919. He was retroactively awarded a Purple Heart for his combat injury in 1945.

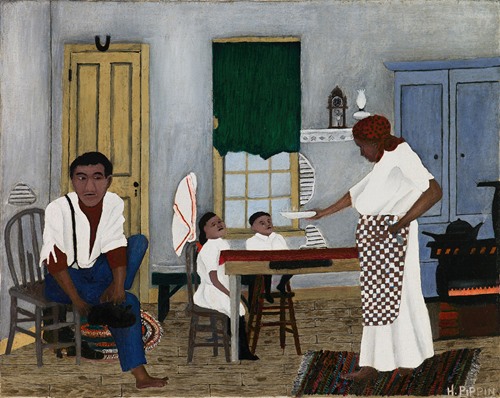

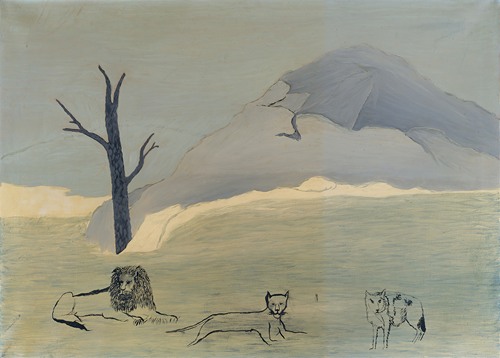

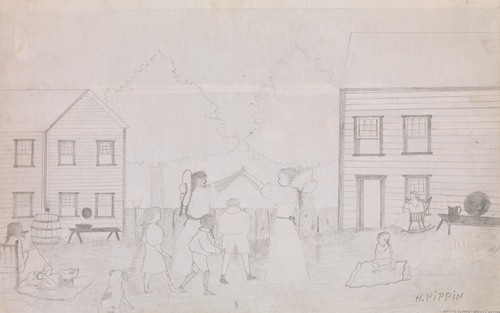

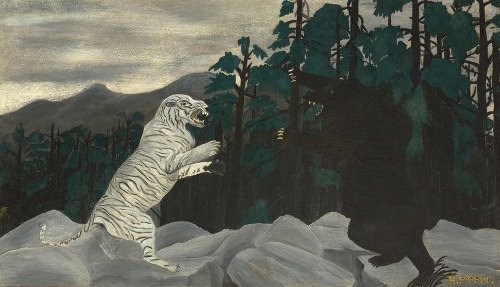

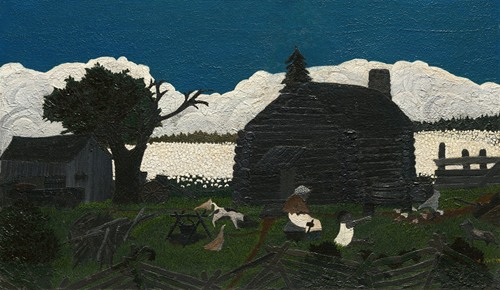

Pippin took up art in the 1920s, reportedly in part to rehabilitate his injured arm, and began painting on stretched fabric in 1930 with The Ending of the War: Starting Home. He later explained his creative process: "The pictures which I have already painted come to me in my mind, and if to me it is a worth while picture, I paint it." He addressed a range of themes, from landscapes and still lifes to biblical subjects and political statements. Some draw on his personal experience of the war or turn-of-the-century domestic life.

He was "discovered" when he submitted two paintings to a local art show—the Chester County Art Association (CCAA) Annual Exhibition—reportedly with the aid and encouragement of various locals, including CCAA co-founders art critic Christian Brinton and artist N.C. Wyeth. Brinton immediately organized a solo exhibition, cosponsored by the CCAA and the interracial West Chester Community Center, connected him with MoMA curators Dorothy Miller and Holger Cahill and, by 1940, the Philadelphia art dealer Robert Carlen and collector Albert C. Barnes. Pippin attended art appreciation classes at the Barnes Foundation in the spring 1940 semester. Carlen, Barnes, and, starting in 1941, dealer Edith Gregor Halpert played prominent roles in Pippin's career.

In the eight years between his national debut in the Museum of Modern Art's traveling exhibition “Masters of Popular Painting” (1938) and his death at the age of fifty-eight, Pippin's recognition grew exponentially across the country and internationally. During this period, he had solo exhibitions in commercial galleries in Philadelphia (1940, 1941) and New York (1940, 1944), and at the Arts Club of Chicago (1941) and San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (1942). Private collections and museums such as the Barnes Foundation, the Philadelphia Museum of Art and the Whitney Museum of American Art acquired his works. His paintings were featured in annual or biennials at the Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, IL; Carnegie Institute, Pittsburgh, PA; Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.; Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia, PA; and the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, as well as thematic surveys at the Dayton Art Institute, OH; National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.; Newark Museum, Newark, NJ; and Tate Gallery, London, UK.

In the catalogue for one of his memorial exhibitions in 1947, critic Alain Locke described Pippin as "a real and rare genius, combining folk quality with artistic maturity so uniquely as almost to defy classification."