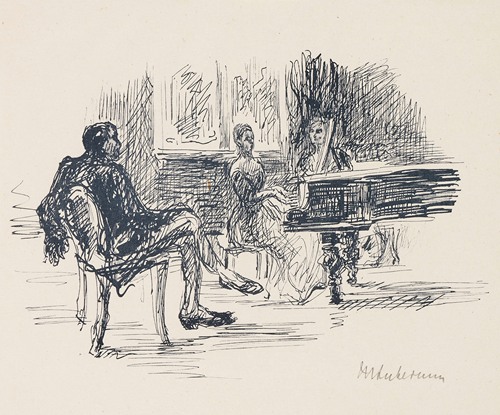

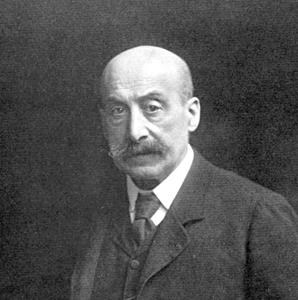

Max Liebermann was a German painter and printmaker of Ashkenazi Jewish ancestry, and one of the leading proponents of Impressionism in Germany.

The son of a Jewish fabric manufacturer turned banker from Berlin, Liebermann grew up in an imposing town house alongside the Brandenburg Gate. He first studied law and philosophy at the University of Berlin, but later studied painting and drawing in Weimar in 1869, in Paris in 1872, and in the Netherlands in 1876–77. During the Franco-Prussian War (1870–71), Liebermann served as a medic with the Order of St. John near Metz. After living and working for some time in Munich, he finally returned to Berlin in 1884, where he remained for the rest of his life. He was married in 1884 to Martha Marckwald (1857–1943).

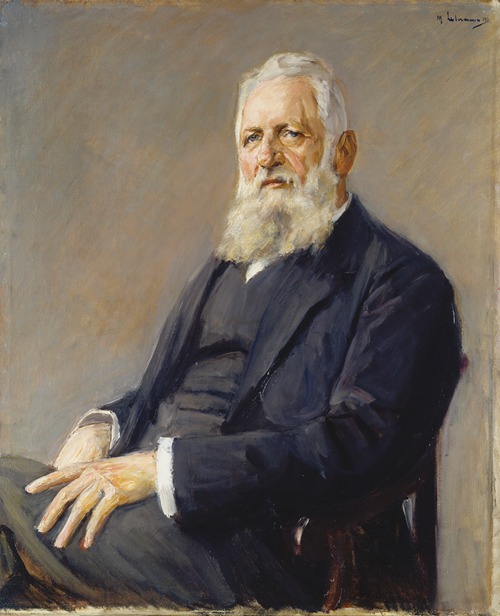

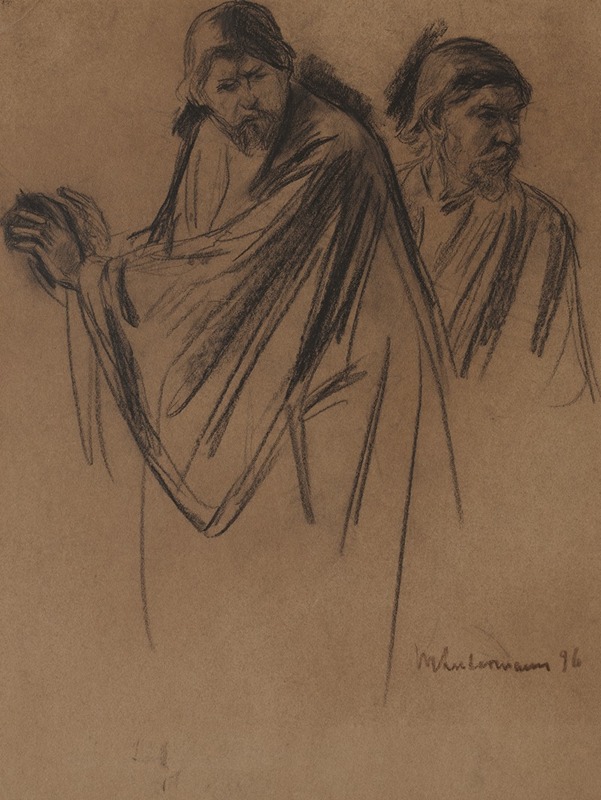

He used his own inherited wealth to assemble an impressive collection of French Impressionist works. He later chose scenes of the bourgeoisie, as well as aspects of his garden near Lake Wannsee, as motifs for his paintings. In Berlin, he became a famous painter of portraits; his work is especially close in spirit to Édouard Manet. In his work he steered away from religious subject matter, with one cautionary exception being an early painting, The 12-Year-Old Jesus in the Temple With the Scholars (1879). His painting of a Semitic-looking boy Jesus conferring with Jewish scholars sparked debate. At the International Art Show in Munich it stirred up a storm for its supposed blasphemy, with one critic describing Jesus as "the ugliest, most impertinent Jewish boy imaginable." Noted for his portraits (he did more than 200 commissioned ones over the years, including of Albert Einstein and Paul von Hindenburg), Liebermann also painted himself from time to time.

On the occasion of his 50th birthday, Liebermann was given a solo exhibition at the Prussian Academy of Arts in Berlin, and the following year he was elected to the academy. From 1899 to 1911 he led the premier avant-garde formation in Germany, the Berlin Secession. In his various capacities as a leader in the artistic community, Liebermann spoke out often for the separation of art and politics. In the formulation of arts reporter and critic Grace Glueck he "pushed for the right of artists to do their own thing, unconcerned with politics or ideology." His interest in French Realism was offputting to conservatives, for whom such openness suggested what they thought of as Jewish cosmopolitanism. He did contribute regularly to a newspaper put out by artists during World War I.

Beginning in 1920 he was president of the Prussian Academy of Arts. On his 80th birthday, in 1927, Liebermann was celebrated with a large exhibition, declared an honorary citizen of Berlin and hailed in a cover story in Berlin's leading illustrated magazine. But such public accolades were short lived. In 1933 he resigned when the academy decided to no longer exhibit works by Jewish artists, before he would have been forced to do so under laws restricting the rights of Jews. While watching the Nazis celebrate their victory by marching through the Brandenburg Gate, Liebermann was reported to have commented: "Ich kann gar nicht soviel fressen, wie ich kotzen möchte." ("I could not possibly eat as much as I would like to throw up.").

His work was part of the painting event in the art competition at the 1928 Summer Olympics.

Liebermann died on February 8, 1935, at his home on Berlin's Pariser Platz, near the Brandenburg Gate. According to Käthe Kollwitz, he fell asleep about 7 p.m. and was gone.