Luis Egidio Meléndez was a Spanish painter. Though he received little acclaim during his lifetime and died in poverty, Meléndez is recognized as the greatest Spanish still-life painter of the 18th century. His mastery of composition and light, and remarkable ability to convey the volume and texture of individual objects enabled him to transform the most mundane of kitchen fare into powerful images.

Luis Egidio Meléndez de Rivera Durazo y Santo Padre was born in Naples in 1716 to Francisco Meléndez de Rivera Diaz (1682 – after 1758) and Maria Josefa Durazo y Santo Padre Barrille. Meléndez's father, a miniaturist painter from Oviedo, had moved to Madrid with his older brother, the portrait painter Miguel Jacinto Meléndez (1679–1734) in pursuit of artistic instruction.

Whereas Miguel remained in Madrid to study and became a painter in the court of Philip V of Spain, Francisco left for Italy in 1699 to seek greater artistic exposure. Francisco took a special interest in visiting the Italian academies and settled in Naples where he married. Meléndez was a year old when his father, who had been a soldier in a Spanish garrison and lived abroad for almost two decades, returned to Madrid with the family. Meléndez, his brother José Agustín, and Ana, one of his sisters, began their careers under the tutelage of their father, who was appointed the King's Painter of Miniatures in 1725.

After several years "painting royal portraits in jewels and bracelets to serve as gifts for envoys and ambassadors", he entered the workshop of Louis Michel van Loo (1707–1771), a Frenchman who had been made royal painter of Philip V. Between 1737 and 1742, Meléndez merely worked as a part of a team of artist dedicated to copy van Loo's prototypes of royal portraits for the domestic and overseas market but had a foothold in the palace. He had his artistic sights on a distinguished career as a court painter.

When the Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando was provisionally inaugurated in 1744, Francisco was made an honorary director of the painting section, and Meléndez was among the first students to be admitted, where he achieved outstanding results in drawing. The Academy was progressive in that it not only tolerated but also encouraged "lesser" genres, including still life.

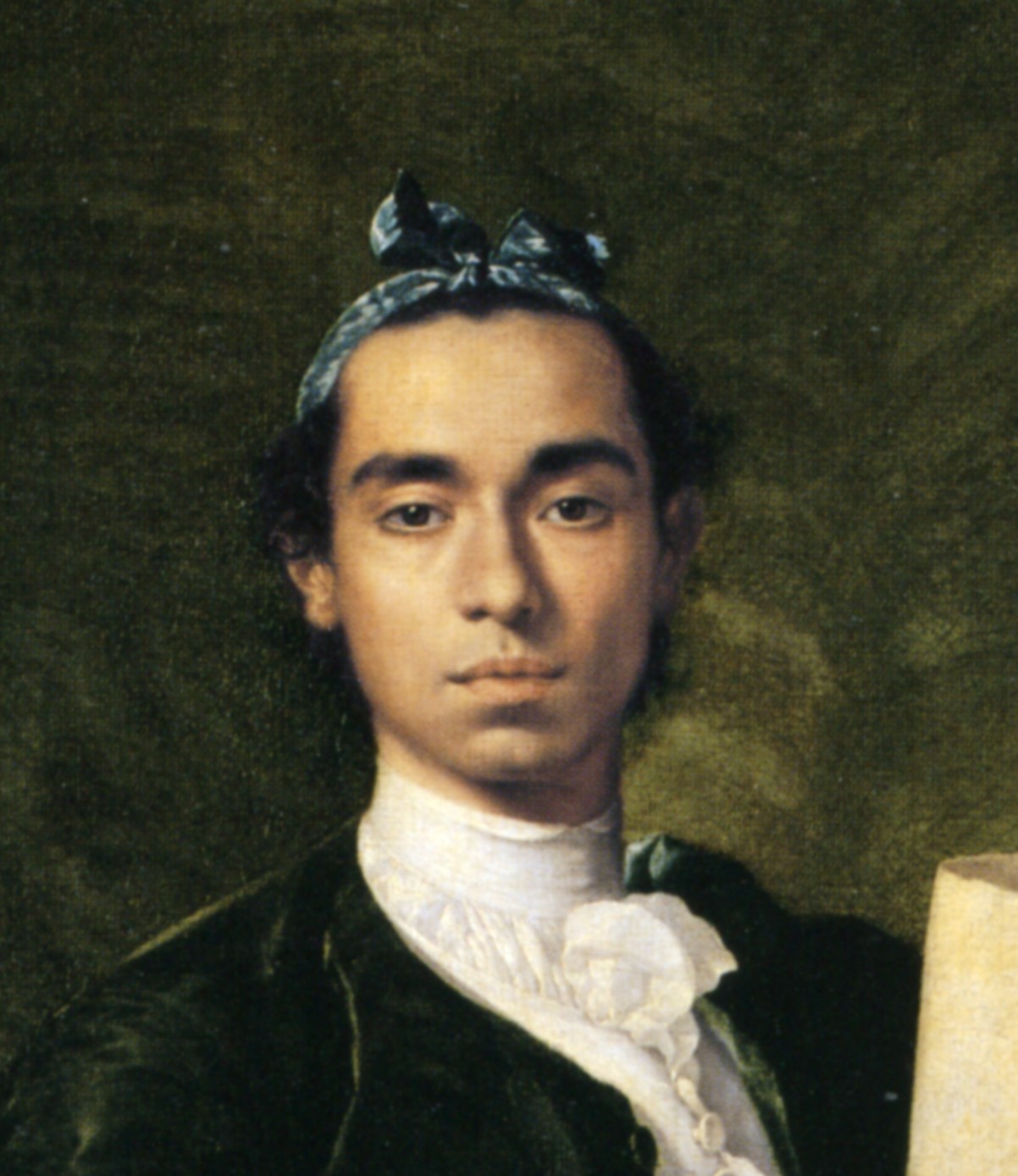

At this time, he was already an accomplished painter, as proven by his self-portrait signed in 1747 at the Louvre. However, a petty quarrel marred this opportunity; Francisco openly attacked the director of the Academy and claimed for himself the honor of being the founder. He had Meléndez personally deliver the inflammatory material to the Academy. Francisco was relieved of his teaching position and Meléndez formally expelled from the Academy on June 15, 1748. Unlike his father, Meléndez's professional status was precarious. Young and self-righteous, without the support of the Academy and his reputation at stake, he decided to go to Italy to get new opportunities, where he remained until 1752. He stayed in Rome and Naples to pursue other career possibilities. There he made some paintings, now lost, for Charles III of Spain, who was then King of Naples.

After a fire at the Alcázar of Madrid in 1753 destroyed scores of illuminated choir books, Francisco coaxed his 37-year-old son to return to Spain to help paint new miniatures. Though Meléndez eventually executed scores of still lifes for the royal household, he did not secure an official appointment to serve the king.

Meléndez worked out of Madrid and initially painted an array of subjects. In 1760 Meléndez's petition for the position of court painter was refused, despite the caliber of his early works. He painted some religious works but began specializing in still life after 1760, a decorative genre that could be produced without commission and was therefore lucrative for artists without royal patronage or the support of the Academy. Between 1759 and 1772, he created at least 44 still lifes for the private museum of natural history belonging to the Prince of Asturias, who later became King Charles IV of Spain. Of these paintings thirty nine are today in the Museo del Prado, and it is rare to find his work outside of Spain.

Despite his talent, Meléndez lived in poverty for most of his life, and in 1772 in a letter to the king he declared that he only owned his pencils. Unappreciated in his time, when he died in Madrid in 1780, he was indigent.