Paul Iribe was a French illustrator and designer in the decorative arts. He worked in Hollywood during the 1920s and was Coco Chanel's lover from 1931 to his death.

Joseph Paul Iribe was born in Angoulême, France in 1883, of a father born in Pau (Béarn), Jules Jean Iribe (1836–1914). Iribe received his education in Paris. From 1908 to 1910 he studied at the École des Beaux-Arts and the College Rollin.

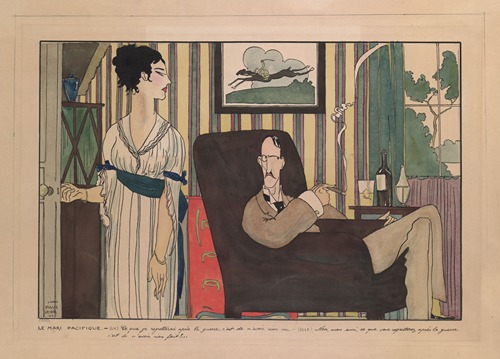

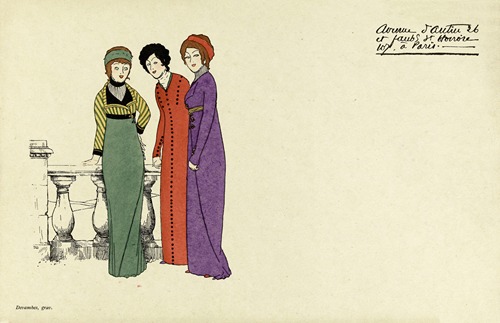

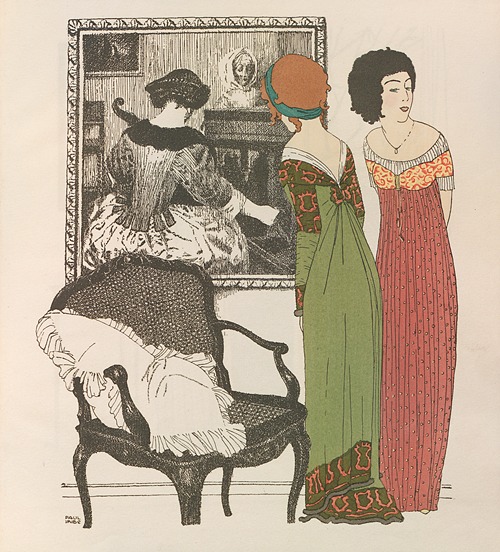

At age seventeen Iribe provided illustrations for the popular L'Assiette au Beurre and also contributed drawings and caricatures for French satirical papers such as Le Rire, Le Sourire, and La Baïonnette. His reputation grew, and it was said, “no one could sketch an event more tellingly.” He was one of a talented group of like illustrators including George Barbier, Georges Lepape, Charles Martin, and Pierre Brissaud. Their modernist style, informed by both the vitality of the revolutionary art movements of the era, and by the flat planes and minimalism identified with Japanese painting served to revitalize the popularity of the fashion plate. These fashion plates were hand colored using the pochoir process, whereby stencils and metal plates are used allowing for colors to be built up and gradually nuanced according to the artist’s vision. The fashion plate, in use for some time, was in essence an advertising tool—a piece of artwork used to create desire for the newest clothing looks aimed at an audience of the fashionable and moneyed. Iribe’s work is primarily distinguished by the illustrations he executed for style journals such as La Gazette du Bon Ton where his charming vignettes of the latest modes helped promote the designs of couturiers such as Paul Poiret. The appeal of these illustrations lay in their depiction of stylish women pursuing the everyday activities of an affluent life style. Iribe's design career was a prolific one, contributing text and visuals to Vogue magazine, designing fabrics, furniture, rugs and doing interior design work for wealthy clients.

Iribe favored the liberal display of fluid forms, more in concordance with the design elements which were the hallmark of the Art Nouveau movement—poufs, lamé textiles; walls hung with tapestries, and carpeted floors. He was hostile to the new school of industrial design, and provided his own terse critique of the Art Deco Exposition of 1925: “the alliance between Art and the cube.”

In 1933, Iribe collaborated with Coco Chanel in the design of extravagant jewelry pieces commissioned by the International Guild of Diamond Merchants. The collection, executed exclusively in diamonds and platinum, was exhibited for public viewing and drew a large audience; some three thousand attendees were recorded in a one-month period.

The couturier Paul Poiret recognized Iribe’s talent and brought him in to create drawings, which would compellingly represent the new models in his collection. These illustrations were later compiled into an album, ”Les Robes de Paul Poiret racontée par Paul Iribe” published in 1908. The book created a controversy, as Poiret’s design aesthetic promoted clothing with a relaxed line, emphatically denouncing the corseted look so long in vogue as the mandated female silhouette. In “Portraits-Souvenirs,” Jean Cocteau made a wry observation: “Iribe’s album disgusts mothers.” Contentious opinion, however, fueled a public debate providing Poiret with the publicity that ultimately brought him success. Poiret’s success also proved a triumph for Iribe.

In 1919 Iribe was in Hollywood recruited for design work by film director Cecil B. DeMille. Iribe and DeMille were ideally paired collaborators sharing a penchant for luxury replete with all the entailing visual drama. DeMille allowed Iribe complete creative freedom. In Hollywood, Iribe practiced the same design sensibilities for which he was renowned in Paris. His depiction of Egypt for DeMille’s 1923 The Ten Commandments was not a Biblical rendition but pure Hollywood fantasy, all lacquered glamour and opulence.

In 1924 Iribe was given free rein in a film project for which he was director, set designer and costumer, Changing Husbands starring Leatrice Joy. The character of the male protagonist represented Iribe himself, the novice director having reconstituted his own image for the screen. The film proved to be a critical disaster. The New York Times gave it a scathing review, calling the film absurd, and the direction “amateurish.”

Iribe was a man prone to anger, shouting matches, and fist fights when contradicted and did not endear himself to colleagues. He engaged in a sustained feud with DeMille’s key costume designer, Mitchell Leisen, which resulted in Leisen being fired by DeMille in 1923. After Iribe’s costly and infamous failure with Changing Husbands, DeMille was forced to make peace with Leisen and bring him back in. For his film The King of Kings (1927), DeMille assigned Leisen as head designer. Now working with Leisen, Iribe made a serious design error for one of the sets and DeMille let him go. "Iribe left Hollywood without any hope of returning there."

Back in Paris, a consolation prize awaited Iribe. His wife Maybelle gave him his own design establishment dedicated to the decorative arts located on the fashionable Rue du Faubourg Saint-Honoré.

The first incarnation of Iribe's journal, Le Témoin ("The Witness"), was published from 1906 to 1910. It was a compendium of social and political satire with artwork by Iribe and contributions by other well-known illustrators of the day. Broadcasting a demonstrable French nationalism, the major illustrations in Le Témoin were always executed in three colors, the blue, white and red of the French flag. The back cover was invariably an advertisement for French commerce—boosterism for French made goods and industry. Signing his work “Jim,” a caricature drawn by the then unknown Jean Cocteau was published in Le Témoin In 1910; his likeness of actress Sarah Bernhardt was well received and brought him instant recognition.

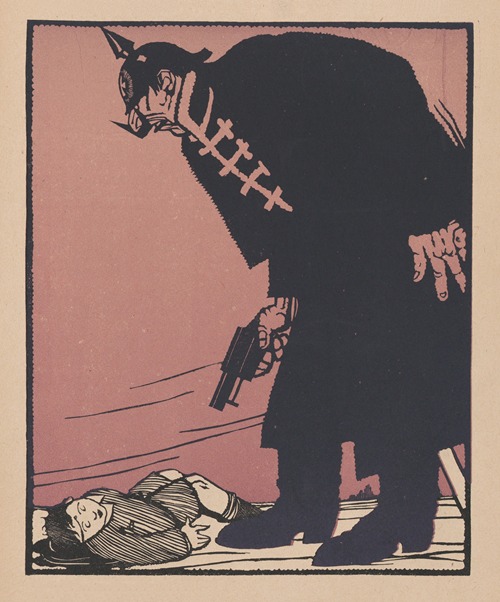

The second appearance of Le Témoin debuted on December 10, 1933, and sixty-nine issues were printed until its demise on June 30, 1935. Iribe’s illustrations were prolific, rendered in dark monotones of black and white punctuated by vivid red. Unlike its earlier version, this second run of Le Témoin contained art solely by Iribe himself. It was re-figured into a strident platform for aggressive patriotism, an ultra-nationalist voice fueling an irrational fear of foreigners and preaching anti-Semitism. Jews are invariably presented as the stereotypical aggregate of menacing “hook-nosed” outsiders, holding France at their mercy.

The drawings, political polemics, featured the identifiable likeness of Iribe’s lover Coco Chanel re-imagined as the iconic symbol of French liberty, Marianne. One such rendering shows Marianne (Chanel) being subjected to trial and sentence by a court of world leaders, Neville Chamberlain of Great Britain, Adolf Hitler of Germany, Benito Mussolini of Italy, and Franklin Roosevelt of The United States. In a corollary illustration, her prostrate figure is lying at the feet of a gravedigger readying to bury the grandeur of France; the gravedigger is Édouard Daladier, the Prime Minister of the French Republic.

Iribe was part of a Parisian, bohemian clique, a cosmopolitan mix of personalities from the world of the arts and elite society. Notable members were Misia Sert, her husband, Spanish painter, José-Maria Sert, Jean Cocteau and his lover, French actor, Jean Marais, Serge Lifar, a member of the Diaghilev ballet, and couturier, Coco Chanel. It was a libertine group rife with emotional, and sexual intrigues—all fueled by drug use and abuse. The writer Colette harbored an instinctive distrust of Iribe. She wrote: "he coos like a dove which makes it all the more interesting, because you will find in old texts that demons assume the voice of Venus." Whenever Iribe approached her in greeting, Colette would demonstrate a mannerism described as a sign of exorcism. Iribe’s involvement with Coco Chanel was particularly intense. Chanel found Iribe’s provocative wit and professional drive matched her own. Theirs was a romantic liaison, and a bond of like souls who shared the same right-wing politics. Chanel financed the publication of Iribe’s journal, Le Témoin in the 1930s.

In 1911, Iribe married actress and variety entertainer Jeanne Dirys. In a stage production of “Le Cadet des Courtas" the same year, she wore a piece of jewelry Iribe had designed in 1910, a luxury turban brooch shaped as an aigrette and inlaid with emerald and pearl. They were divorced in 1918.

Iribe's second wife was Maybelle Hogan, an heiress who had previously been married to Francis C Coppicus, a theatrical and musical manager. They had two children, Pablo (born in 1920) and Maybelle (born 1928). They separated in 1928, as a result of Iribe’s involvement with Coco Chanel.

By 1933, friends of Chanel and Iribe were convinced that the two were engaged to be married and that a wedding was imminent.

Iribe was with Coco Chanel, at her villa, La Pausa, on the French Riviera, in September 21, 1935, when he suddenly collapsed and died while playing tennis. Chanel witnessed his death, and felt his loss deeply, grieving over him for a protracted period of time.