John Philip Falter, more commonly known as John Falter, was an American artist best known for his many cover paintings for The Saturday Evening Post.

Born in Plattsmouth, Nebraska, Falter moved at an early age with his family to Falls City in 1916, where his father, George H. Falter, established a clothing store. As a high school student, Falter created a comic strip, Down Thru the Ages, which was published in the Falls City Journal. J. N. "Ding" Darling, Pulitzer Prize-winning cartoonist of the Des Moines Register, saw some of Falter’s cartoons and said he should become an illustrator.

After graduating from high school in 1928, Falter studied at the Kansas City Art Institute where he met and became friends with R. G. Harris, Emery Clarke, and Richard E. Lyon. He won a scholarship to the Art Students League of New York City, but lasted only one month there due to his fear of his fellow students, many of whom were avowed Communists. This was all too new for the small-town Falter, who fled and immediately looked for work as an illustrator. In the evenings, he took courses at the Grand Central School of Art above Grand Central Terminal. At this time in the Great Depression, when most young artists had difficulty finding work, Falter began illustrating covers for pulp magazines.

He opened a studio in New Rochelle, New York, which had long been a colony for illustrators, including such artists as Frederic Remington and Norman Rockwell. Within a few years, his three Kansas City Art Institute friends Harris, Clarke and Lyon had moved to New Rochelle to share a studio with Falter and launch their careers as freelance illustrators. Falter recalled, "Rockwell was our inspiration then. I didn't meet him until years later. We would hear that Rockwell had been out on the street. and we'd all rush out and hunt for him. If they'd tell us that he had looked in a shop window, we'd look in the same window trying to absorb what he looked at by osmosis."

Falter received a major break with his first commission from Liberty Magazine to do three illustrations a week in 1933. "They paid me $75 a week," Falter said, "just like a steelworker. But my expenses for models and costumes were running $35 a week during one 16-week serial I was illustrating." Falter soon discovered that there was much more money to be made in advertising than in other fields of illustration. By 1938, he had acquired several advertising clients including Gulf Oil, Four Roses Whiskey, Arrow Shirts and Pall Mall. Falter's work appeared in major national magazines. "This was high pay for less work," Falter said, "and it gave me a chance to experiment in the field of easel painting."

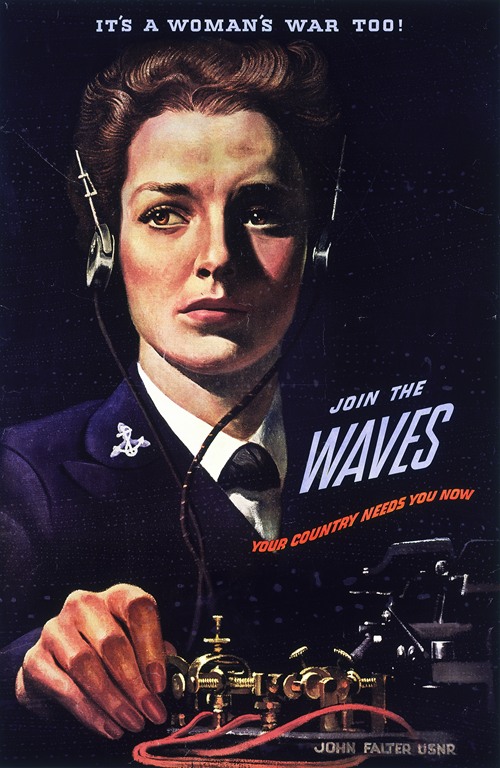

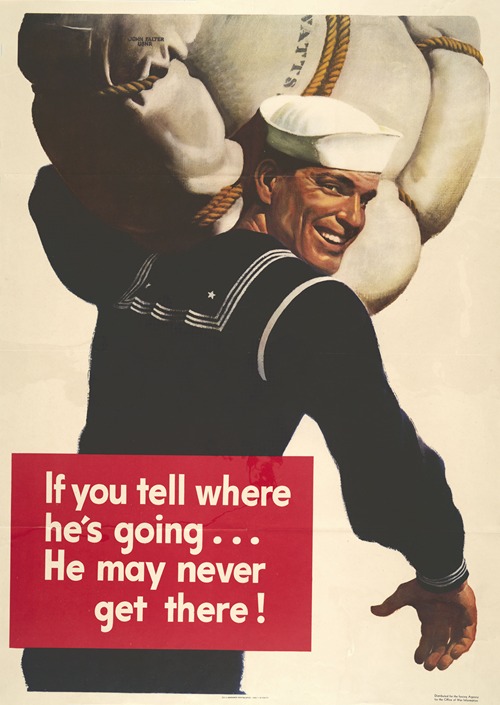

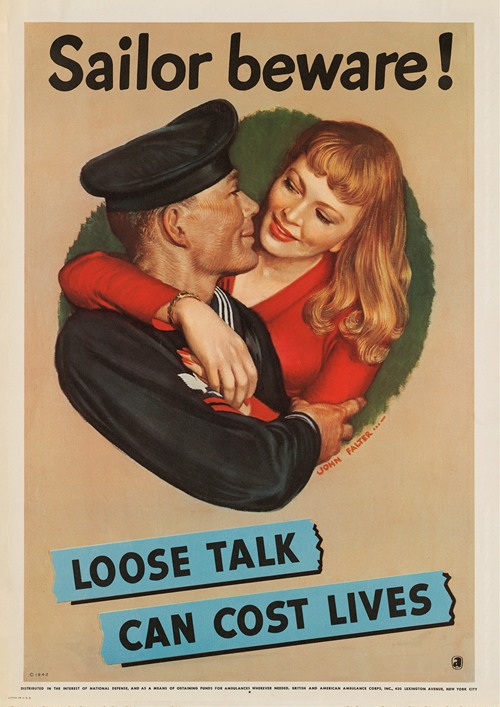

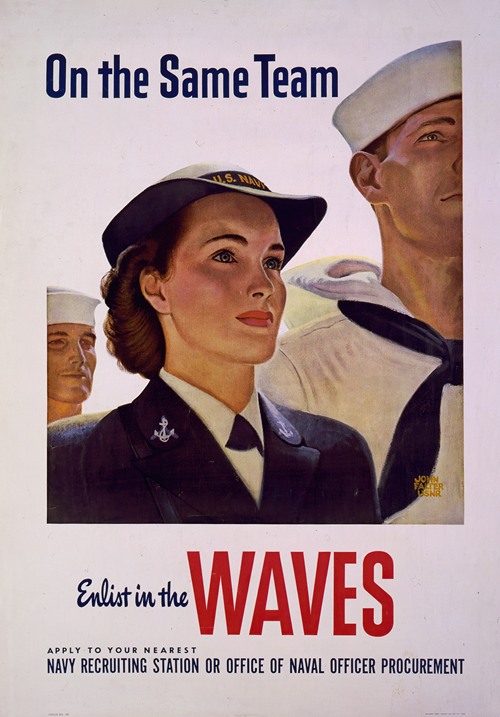

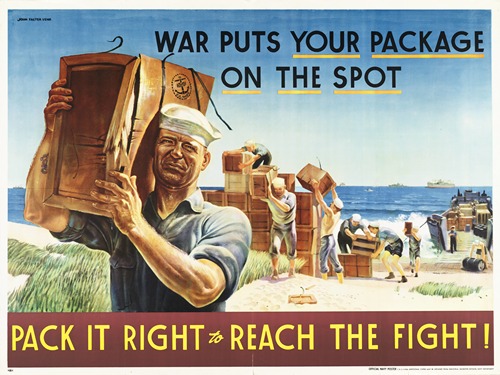

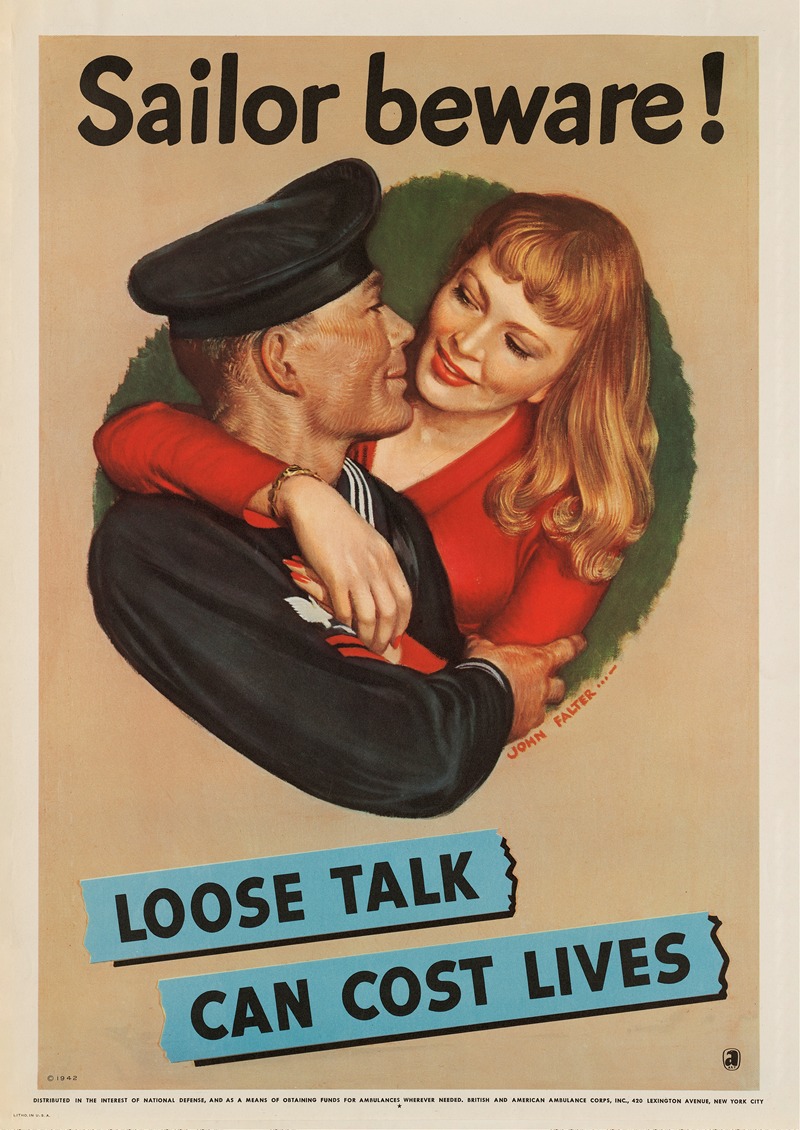

In 1943, he enlisted in the Navy and was rapidly promoted from chief boatswain's mate to lieutenant on special assignment as an artist. His final rank was Chief Petty Officer. His talents were applied to the American war effort to spur on recruiting drives. Falter designed over 300 recruiting posters. One popular Falter poster dealt with the loose-lips-sink-ships theme. It showed a broad-shouldered Navy man with the caption, "If you tell where he's going, he may never get there." During this period, he also completed a series of recruiting posters for the women's Navy (WAVES), and a series of 12 Medal of Honor winners for Esquire.

Falter's first Saturday Evening Post cover, a portrait of the magazine's founder, Benjamin Franklin, is dated January 10, 1943. It began a 25-year relationship with the magazine, for whom Falter produced over 120 covers until the editors changed its cover format to photographs. Falter commented, "There were plenty of Rockwell imitators and J. C. Leyendecker imitators. My main concern in doing Post covers was trying to do something based on my own experiences. I found my niche as a painter of Americana with an accent of the Middle West. I brought out some of the homeliness and humor of Middle Western town life and home life. I used humor whenever possible." Nearly all of Falter's 120-odd covers were his own ideas. "Four didn't make it, [and] probably 12 ideas were supplied by the Post," he said. Many of his friends acted as models for his covers; four of them depict his close friend, the actor J. Scott Smart.

Falter said that he tried "to put down on canvas a piece of America, a stage set, a framework for the imagination to travel around in." His panoramic covers with long views of people were a major departure from the Post's customary close-up designs. Norman Rockwell himself adjusted to the newer style for a time, which he later referred to as his "Falter Period."

Falter once thought that The Saturday Evening Post would provide him with lifetime employment. "I was sort of going along on a ship that would never sink," he said. “It seemed that nothing could possibly happen to the Post. Then suddenly, in my middle life, I had to retool and give up my horse for a car." Falter was forced to spend much of his savings in the months that followed the demise of the Post.

Although best known for his Saturday Evening Post covers, of which he produced 129, Falter also provided illustrations for numerous other publications, including Esquire, Good Housekeeping, Cosmopolitan, McCall's, Life Magazine and Look.

Falter was a prolific artist who depicted a wide range of subject matter in a variety of media. As television eliminated many national magazines in the 1950s and 1960s, he turned to portrait painting and book illustration. He illustrated over 40 books. One of his favorite projects was illustrating a special edition of Carl Sandburg's Abraham Lincoln—The Prairie Years. Other favorite book projects included Houghton-Mifflin's Mark Twain series and illustrations for The Scarlet Pimpernel. His stepson, Jay Wiley, posed for a book Falter illustrated, Me 'n Steve. A final favorite was humorist Corey Ford's The Horse of a Different Color.

Falter produced a body of work impressive in volume and variety. Reflecting a lifelong interest in jazz, he did scenes of Harlem nightclub life in the 1930s, and later, portraits of famous jazz musicians. An excellent portrait painter, Falter had Clark Gable, James Cagney, Olivia de Havilland and Admiral "Bull" Halsey among his sitters. He was an accomplished jazz clarinet player, entirely self-taught. He took great pleasure in visiting jazz friends at clubs such as Eddie Condon's in New York City, where he would sketch the musicians live, then sit in on clarinet.

As the age of illustrated magazines ended during the 1970s and 1980s, Falter turned to his passions for historical and American Western themes. The 3M Company commissioned him for a series of six paintings in celebration of the American Bicentennial, titled From Sea to Shining Sea. Falter completed over 200 paintings in the field of Western art, with emphasis on the migration of 1843 to 1880 from the Missouri River to the Rocky Mountains. His peers honored him with election to the Illustrators Hall of Fame] in 1976, and membership in the National Academy of Western Art in June 1978.

When Falter was asked to look back over his career, he commented that he had never created a painting that he wouldn't like to do over; he always saw something he thought he could improve on. His output was prodigious, and by his own reckoning included over 5,000 paintings, many of which hang in museums and eminent collections.

In 1980, a documentary video, "A View from the Standpipe: John Falter's World," was released by Nebraska Educational Television. It features one-on-one interviews with people who knew the artist in his Philadelphia location, and shows a number of his paintings, including some of Falter's personal paintings not often seen by the general public. These paintings are different from his usual subjects, and often contain humorous touches not obvious on first viewing. One example, "The Big Spender," is a beautiful Vermeer-like still life of a dinner plate, crystal glass and linen napkin, where a huge fly is just visible as it heads for the plate.

John Falter died in May, 1982, at the age of 72, at the University of Pennsylvania Hospital in Philadelphia after suffering a stroke. He was living in the Chestnut Hill section of Philadelphia. After his death, Falter's widow, Mary Elizabeth Falter, donated several paintings, personal papers, and memorabilia from his studio to the Nebraska State Historical Society. The material reflects Falter's career from 1930 to 1982.