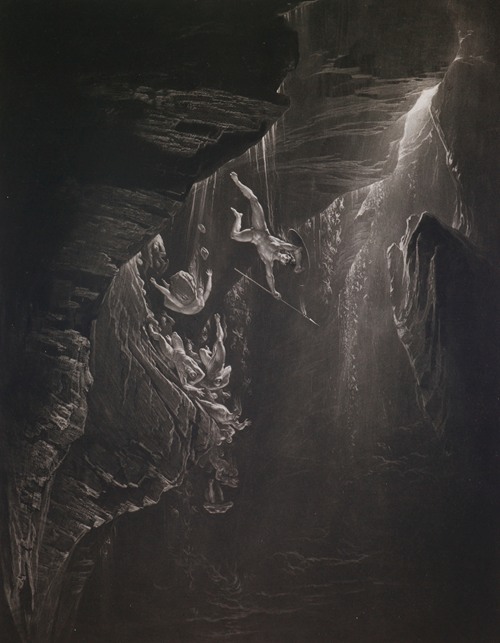

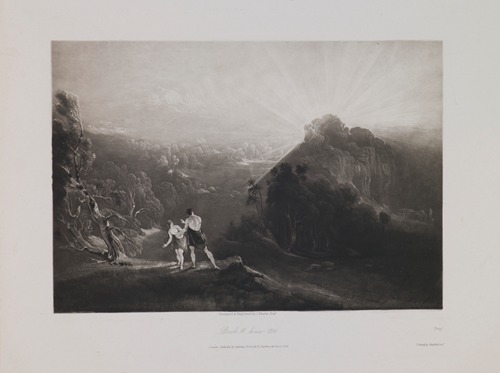

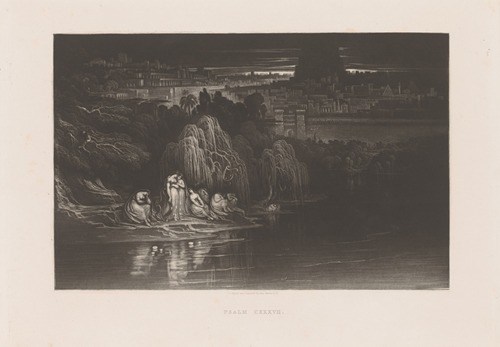

John Martin was an English Romantic painter, engraver and illustrator. He was celebrated for his typically vast and melodramatic paintings of religious subjects and fantastic compositions, populated with minute figures placed in imposing landscapes. Martin's paintings, and the prints made from them, enjoyed great success with the general public—in 1821 Thomas Lawrence referred to him as "the most popular painter of his day"—but were lambasted by John Ruskin and other critics.

Martin was born in July 1789, in a one-room cottage, at Haydon Bridge, near Hexham in Northumberland, the fourth son of Fenwick Martin, a one-time fencing master. He was apprenticed by his father to a coachbuilder in Newcastle upon Tyne to learn heraldic painting, but owing to a dispute over wages the indentures were cancelled, and he was placed instead under Boniface Musso, an Italian artist, father of the enamel painter Charles Muss.

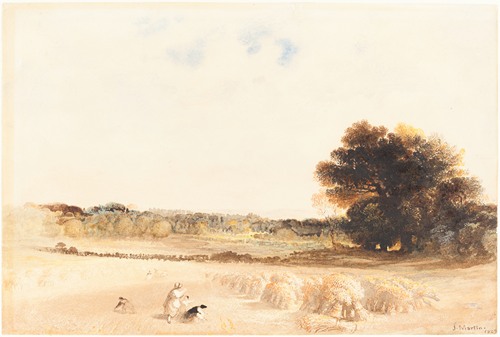

With his master, Martin moved from Newcastle to London in 1806, where he married at the age of nineteen, and supported himself by giving drawing lessons, and by painting in watercolours, and on china and glass—his only surviving painted plate is now in a private collection in England. His leisure was occupied in the study of perspective and architecture.

His brothers were William, the eldest, an inventor; Richard, a tanner who became a soldier in the Northumberland Fencibles in 1798, rising to the rank of Quartermaster Sergeant in the Grenadier Guards and fought in the Peninsular War and at Waterloo; and Jonathan, a preacher tormented by madness who set fire to York Minster in 1829, for which he stood trial.

Martin began to supplement his income by painting sepia watercolours. He sent his first oil painting to the Royal Academy in 1810, but it was not hung. In 1811 he sent the painting once again, when it was hung under the title A Landscape Composition as item no.46 in the Great Room. Thereafter, he produced a succession of large exhibited oil paintings: some landscapes, but more usually grand biblical themes inspired by the Old Testament. His landscapes have the ruggedness of the Northumberland crags, while some authors claim that his apocalyptic canvasses, such as The Destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah, show his familiarity with the forges and ironworks of the Tyne Valley and display his intimate knowledge of the Old Testament.

In the years of the Regency from 1812 onwards there was a fashion for such ‘sublime’ paintings. Martin's first break came at the end of a season at the Royal Academy, where his first major sublime canvas Sadak in Search of the Waters of Oblivion had been hung—and ignored. He brought it home, only to find there a visiting card from William Manning MP, who wanted to buy it from him. Patronage propelled Martin's career.

This promising career was interrupted by the deaths of his father, mother, grandmother and young son in a single year. Another distraction was William, who frequently asked him to draw up plans for his inventions, and whom he always indulged with help and money. But, heavily influenced by the works of John Milton, he continued with his grand themes despite setbacks. In 1816 Martin finally achieved public acclaim with Joshua Commanding the Sun to Stand Still upon Gibeon, even though it broke many of the conventional rules of composition. In 1818, on the back of the sale of the Fall of Babylon for £420 (equivalent to £30,000 in 2015), he finally rid himself of debt and bought a house in Marylebone, where he came into contact with artists, writers, scientists and Whig nobility.