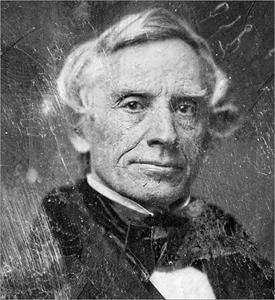

Samuel Finley Breese Morse was an American inventor and painter. After having established his reputation as a portrait painter, in his middle age Morse contributed to the invention of a single-wire telegraph system based on European telegraphs. He was a co-developer of Morse code and helped to develop the commercial use of telegraphy.

Samuel F. B. Morse was born in Charlestown, Massachusetts, the first child of the pastor Jedidiah Morse (1761–1826), who was also a geographer, and his wife Elizabeth Ann Finley Breese (1766–1828). His father was a great preacher of the Calvinist faith and supporter of the American Federalist party. He thought it helped preserve Puritan traditions (strict observance of Sabbath, among other things), and believed in the Federalist support of an alliance with Britain and a strong central government. Morse strongly believed in education within a Federalist framework, alongside the instillation of Calvinist virtues, morals, and prayers for his first son. His first ancestor in America was Samuel Morse, who emigrated to Dedham, Massachusetts in 1635.

After attending Phillips Academy in Andover, Massachusetts, Samuel Morse went on to Yale College to receive instruction in the subjects of religious philosophy, mathematics, and science of horses. While at Yale, he attended lectures on electricity from Benjamin Silliman and Jeremiah Day and was a member of the Society of Brothers in Unity. He supported himself by painting. In 1810, he graduated from Yale with Phi Beta Kappa honors.

Morse married Lucretia Pickering Walker on September 29, 1818, in Concord, New Hampshire. She died on February 7, 1825, of a heart attack shortly after the birth of their third child. (Susan b. 1819, Charles b. 1823, James b. 1825). He married his second wife, Sarah Elizabeth Griswold on August 10, 1848, in Utica, New York and had four children (Samuel b. 1849, Cornelia b. 1851, William b. 1853, Edward b. 1857).

Morse expressed some of his Calvinist beliefs in his painting, Landing of the Pilgrims, through the depiction of simple clothing as well as the people's austere facial features. His image captured the psychology of the Federalists; Calvinists from England brought to North America ideas of religion and government, thus linking the two countries. This work attracted the attention of the notable artist, Washington Allston. Allston wanted Morse to accompany him to England to meet the artist Benjamin West. Allston arranged—with Morse's father—a three-year stay for painting study in England. The two men set sail aboard the Libya on July 15, 1811.

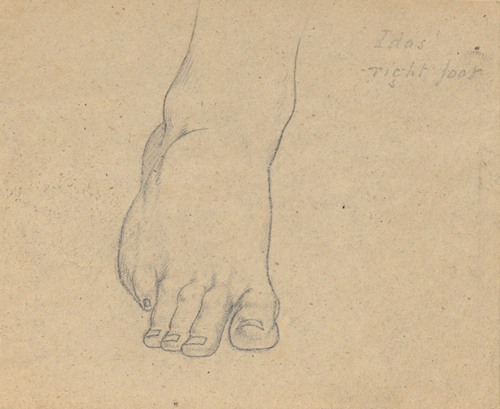

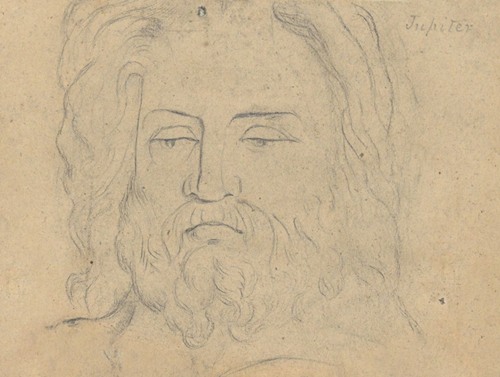

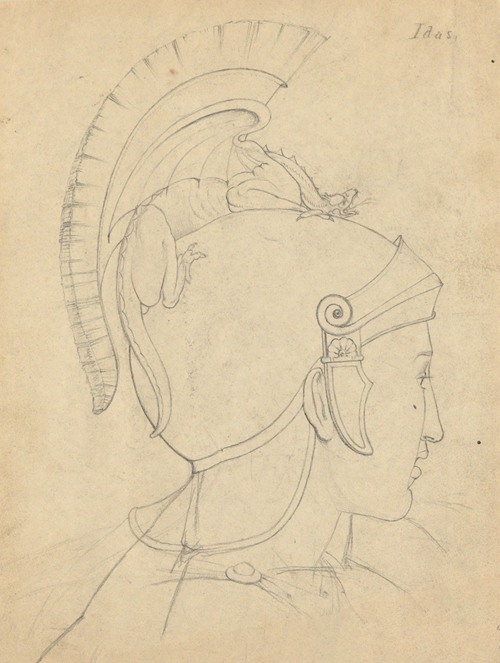

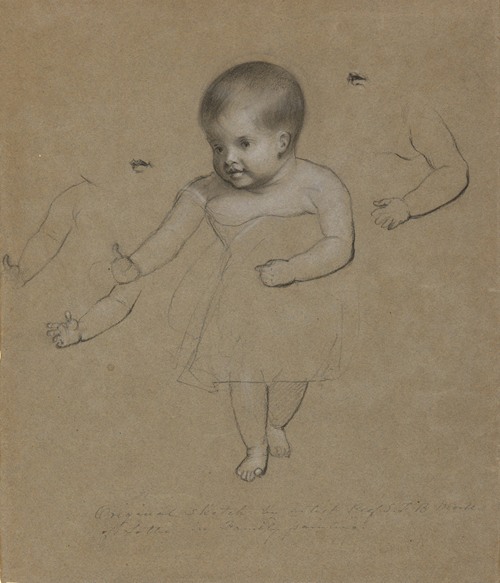

In England, Morse perfected his painting techniques under Allston's watchful eye; by the end of 1811, he gained admittance to the Royal Academy. At the Academy, he was moved by the art of the Renaissance and paid close attention to the works of Michelangelo and Raphael. After observing and practicing life drawing and absorbing its anatomical demands, the young artist produced his masterpiece, the Dying Hercules. (He first made a sculpture as a study for the painting.)

The decade 1815–1825 marked significant growth in Morse's work, as he sought to capture the essence of America's culture and life. He painted the Federalist former President John Adams (1816). The Federalists and Anti-Federalists clashed over Dartmouth College. Morse painted portraits of Francis Brown—the college's president—and Judge Woodward (1817), who was involved in bringing the Dartmouth case before the U.S. Supreme Court.

Morse maintained a studio at 94 Tradd St., Charleston, South Carolina, for a short period.

Morse also sought commissions among the elite of Charleston, South Carolina. Morse's 1818 painting of Mrs. Emma Quash symbolized the opulence of Charleston. The young artist was doing well for himself. Between 1819 and 1821, Morse went through great changes in his life, including a decline in commissions due to the Panic of 1819.

Morse was commissioned to paint President James Monroe in 1820. He embodied Jeffersonian democracy by favoring the common man over the aristocrat.

Morse had moved to New Haven. His commissions for The House of Representatives (1821) and a portrait of the Marquis de Lafayette (1825) engaged his sense of democratic nationalism. The House of Representatives was designed to capitalize on the success of François Marius Granet's The Capuchin Chapel in Rome, which toured the United States extensively throughout the 1820s, attracting audiences willing to pay the 25-cent admission fee.

In 1826, he helped found the National Academy of Design in New York City. He served as the Academy's president from 1826 to 1845 and again from 1861 to 1862.

From 1830 to 1832, Morse traveled and studied in Europe to improve his painting skills, visiting Italy, Switzerland, and France. During his time in Paris, he developed a friendship with the writer James Fennimore Cooper. As a project, he painted miniature copies of 38 of the Louvre's famous paintings on a single canvas (6 ft. x 9 ft), which he entitled The Gallery of the Louvre. He completed the work upon his return to the United States.

On a subsequent visit to Paris in 1839, Morse met Louis Daguerre. He became interested in the latter's daguerreotype—the first practical means of photography. Morse wrote a letter to the New York Observer describing the invention, which was published widely in the American press and provided broad awareness of the new technology. Mathew Brady, one of the earliest photographers in American history, famous for his depictions of the Civil War, initially studied under Morse and later took photographs of him.