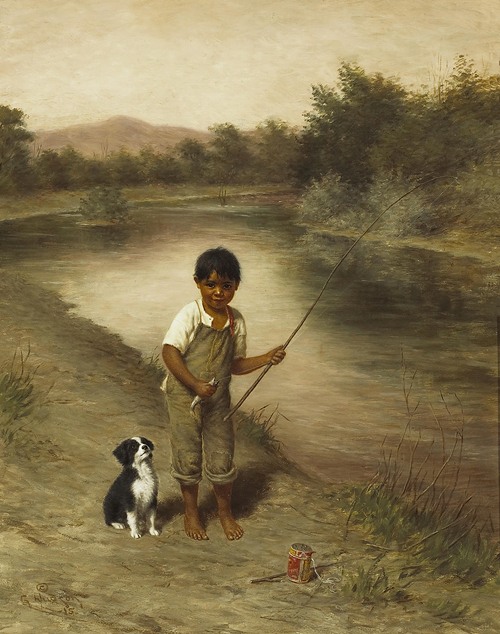

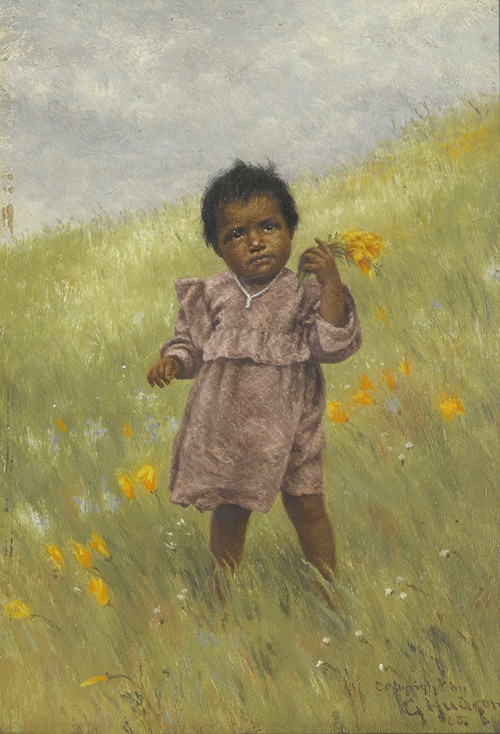

Grace Carpenter Hudson was an American painter. She was nationally known during her lifetime for a numbered series of more than 684 portraits of the local Pomo Indians. She painted the first, "National Thorn", after her marriage in 1891, and the last in 1935.

Grace Carpenter was born on February 21, 1865 in Potter Valley, California. Her mother Helen McCowen was one of the first white school teachers educating Pomo children and was a commercial portrait photographer in Ukiah, California; her father Aurelius Ormando Carpenter was a skilled panoramic and landscape photographer who chronicled early Mendocino County frontier enterprises such as logging, shipping and railroading. Her paternal grandmother was Clarina I. H. Nichols.

At fourteen years of age, Grace was sent to attend the recently established San Francisco School of Design, an art school which emphasized painting from nature rather than from memory or by copying existing works. At sixteen, she executed an award-winning, full length, life sized self-portrait in crayon. While in San Francisco, she met and eloped with a man fifteen years her senior named William Davis, upsetting her parents and ending her formal studies. The marriage lasted only a year.

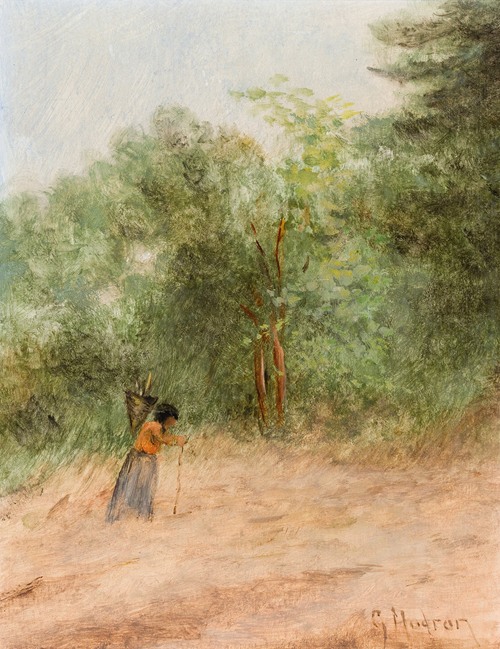

From 1885 to 1890, Grace Carpenter Davis lived with her parents in Ukiah painting, teaching and rendering illustrations for magazines such as Cosmopolitan and Overland Monthly. Her work at that time had no particular focus and included genre, landscapes, portraits and still lifes in all media. Later in her career she would continue to accept occasional magazine illustration assignments including ones for Sunset.

In 1890, Grace married John Wilz Napier Hudson, M.D. (1857–1936) who had come to California from Nashville, Tennessee in 1889 to serve as physician for the San Francisco and North Pacific Railroad. The newlyweds shared a keen interest in preserving and recording Native American culture.

Grace Carpenter Hudson painted "National Thorn" in 1891; it was selected to be shown at the Minneapolis Art Association exhibit where it proved very popular. Her painting "Little Mendocino" (another Pomo infant portrait) was exhibited in the California State Building at the 1893 Chicago World's Fair. The painting received much attention and it earned an honorable mention. In 1894, "Little Mendocino" was hung at the Midwinter Fair in San Francisco, yielding further commissions for works in a similar vein.

By 1895, Grace's growing success as a popular artist was bringing in more than enough money for the couple to live in modest comfort. John Hudson gave up his medical practice in order to study the Pomo people and follow his deep interests in archeology and ethnography. His collection of California Indian baskets and other Native American artifacts can be found in the Smithsonian Institution, the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago, the Brooklyn Museum and the Grace Hudson Museum in Ukiah, whose research collection is based on his manuscripts and correspondence.

An 1895 San Francisco Call piece on Grace was reprinted in the November 5th, 1895 issue of The New York Times, entitled "Very Hard to Get Papooses to Pose." In it, she details her method of photographing or painting Pomo infants without their mother's knowledge, and likely against their will, by means of deceit. Grace reports that due to the indigenous belief that being sketched or photographed would result in a negative outcome, she must use elaborate ruses to access the infants in private.

Grace meticulously photographed and documented each of her works from this time forward; she was concerned with the proliferation of counterfeit copies being produced. Her notes were intended to establish her copyright. Each of her works are numbered in sequence. She often used the camera as the initial basis for her oil portraits, as it allowed the human subject to be captured quickly. She took pains to conceal this practical convenience from the art world as it was considered an inferior method at the time.

In 1900-1901, Grace Hudson had become exhausted from supplying the demand for her popular paintings; she took a solo vacation in the Territory of Hawaii, relaxing and refreshing herself. While there, she completed 26 paintings of Island scenes and Japanese, Chinese and Hawaiian people. While Grace was away, John Hudson became the Pacific Coast ethnologist for the Field Columbian Museum, documenting Northern California native activities including an extensive study of aboriginal fish trapping methods.

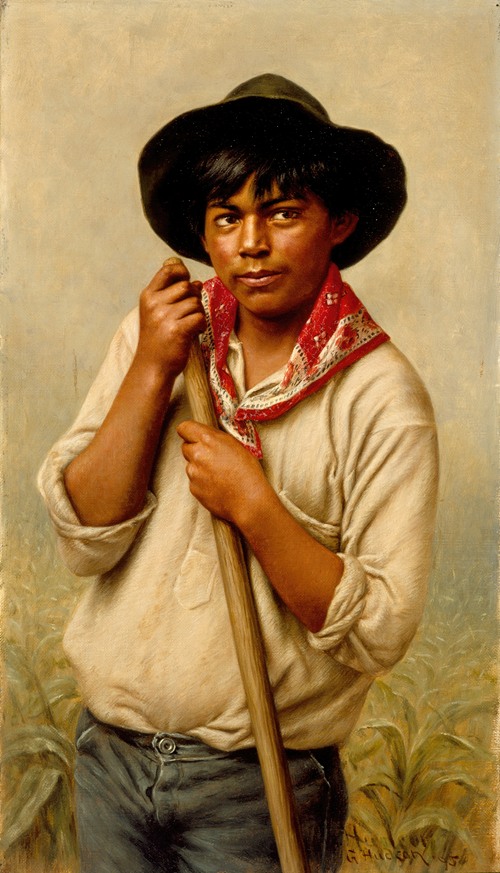

Returning to the mainland, Grace rejoined her husband and resumed work supplying sentimental Pomo portraits to eager buyers as well as accompanying John on much of his field work. In 1902, she painted a portrait of a Pawnee boy; John Hudson had been working to document the Pawnee on assignment for the Field Columbian Museum. In 1904, Grace Hudson accepted a commission from the Field Columbian Museum to take up residence in the Oklahoma Territory and paint further images of the remaining Pawnee, a people who had been nearly wiped out by contact with European diseases. There she preserved primarily chiefs and elders on canvas and photographic negative. Some of the Hudson's collected artifacts and Grace's paintings were destroyed in San Francisco's calamitous fire following the 1906 earthquake while they were in Oklahoma.