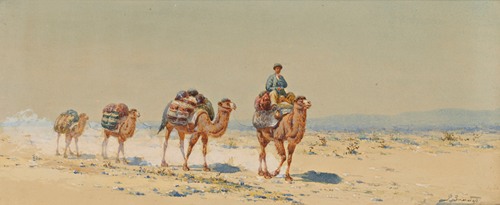

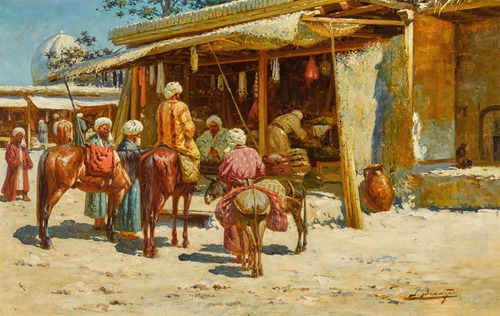

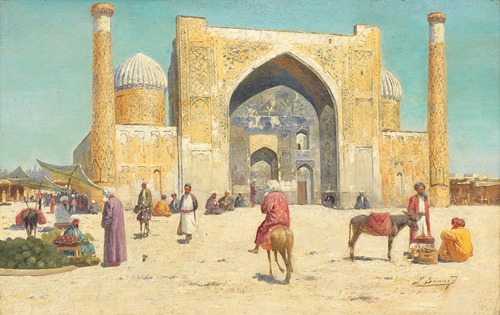

The artist and graphic designer Richard Karlovich Zommer was born in Munich in 1866. From 1884 he studied at the St. Petersburg Academy of Fine Arts and had considerable success, receiving several awards for his work. Zommer’s most prolific period relates to the last decade of the nineteenth century, which he spent in Asia, where he was sent in an archaeological expedition and worked as an ethnologist. During this period he produced a series of portraits, landscapes and works on paper, twenty of which can be found in the Museum of Uzbekistan.

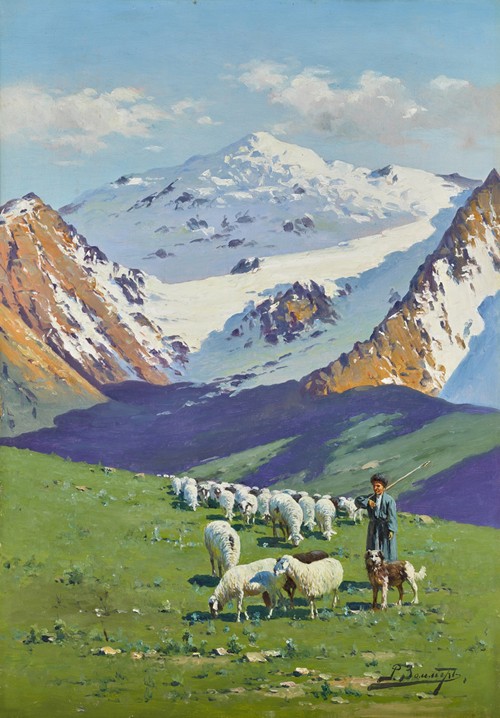

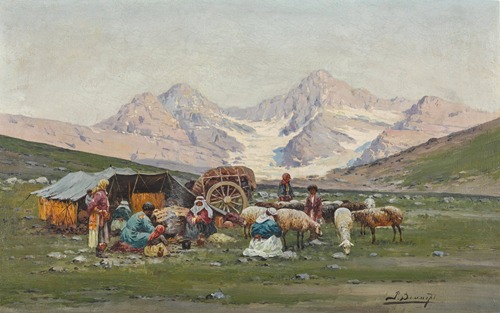

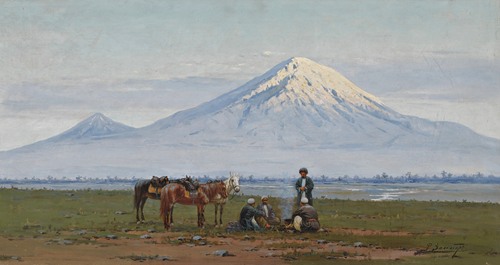

At the beginning of the twentieth century Zommer went to Georgia, where he led an active life, travelling extensively. He walked almost the entirety of the Caucasus Mountains and produced a number of works during this period that provide a fascinating insight into the Caucasus from an ethnographic point of view, as well as glimpses of everyday occurrences and situations. His charming works characteristically display his love for truth and simplicity, and are executed using deep strong colours. Each of his works is particular in its composition, and each tells a story.

Many Georgian artists in the course of the twentieth century were forced to take on governmental jobs, however Zommer succeeded as a preserver of Georgian arts. Describing the world as it truly was, he was a guardian of truth and key in the creative development of Georgian painter Lado Gudiashvili.

Zommer was Gudiashvili’s first teacher and it was Zommer who encouraged the young talented artist to enrol at the Academy of arts in Tbilisi. The academy had a series of distinguished teachers including the Italian painter Longo, the German painter Oskar Schmerling, and the Georgian painter Jakob Nikolades, student of the French sculpture August Rodin. Gudiashvili thought fondly of Zommer, recalling that he was a very articulate, jovial man with red hair, who was popular with everybody and always wore a red scarf around his neck: ’I saw him as someone who stepped out of a Rembrandt painting’.

Zommer had predicted a great career for Gudiashvili, and in December 1926, the two exhibited together at an exhibition in Tbilisi. Gudiashvili was by now well known and had his own distinct style. However, one wonders whether Gudiashvili’s passion for Georgia and its landscape was perhaps instilled by Zommer’s own particular and relentless obsession with the diversity of the surrounding landscape.

Zommer was a member of many art groups, and exhibited at various exhibitions in St. Petersburg between 1916 and 1920. He was one of the founders of the Society for Encouraging the Caucasian Decorative Arts in Tbilisi, and took part in various exhibitions organised by the Caucasian painters society, between 1916 and 1920 in Tbilissi, in Baku in 1907 and in Taschkent in 1915.

For one of Zommer’s exhibitions, the Georgian journalist Michael Dschawachisschwili wrote a review in the newspaper Znobis Purzeli. Dschawachischwili praised Zommer as a great artist, able to express a form of realism in an outstanding way. He commented: ‘There is liveliness and holiness reflected in his landscapes, portraits and in his representations of historical monuments.’

During the 1930s, Georgian intellectuals and artists suffered under the Stalinist regime, and in 1939 Zommer was forced to leave Georgia. After this period his exact whereabouts are unknown, this can in part be explained by the fact that all ethnic Germans were relocated to Siberia and Kazakhstan before World War II.

What is clear is that Zommer had a remarkable and dynamic life. Always on the move, he explored man and his character, creating pictures in his individual and unique way, and provided an important role in the history of twentieth century Georgian painting.