Jules Bourgoin was a pioneer in the study of the finer details of Islamic art.

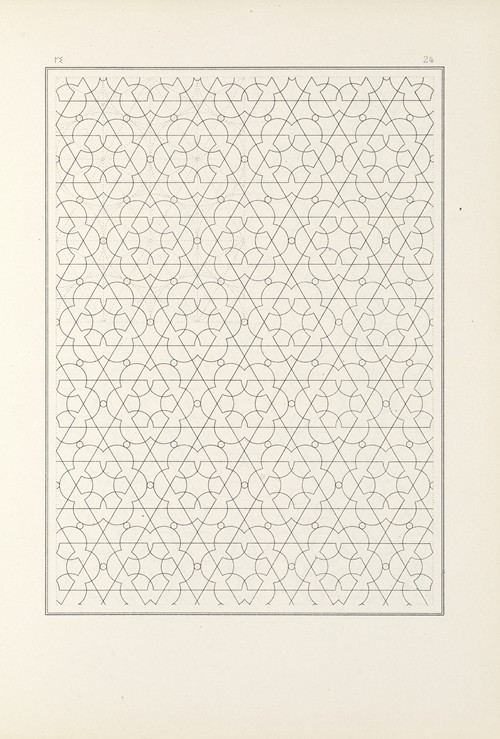

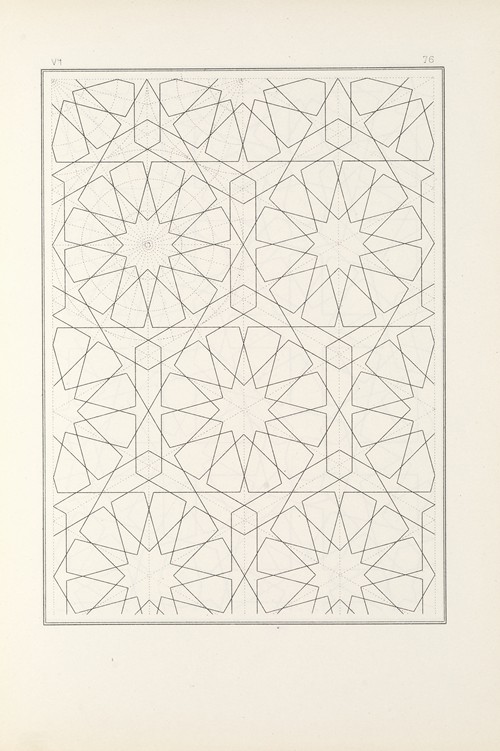

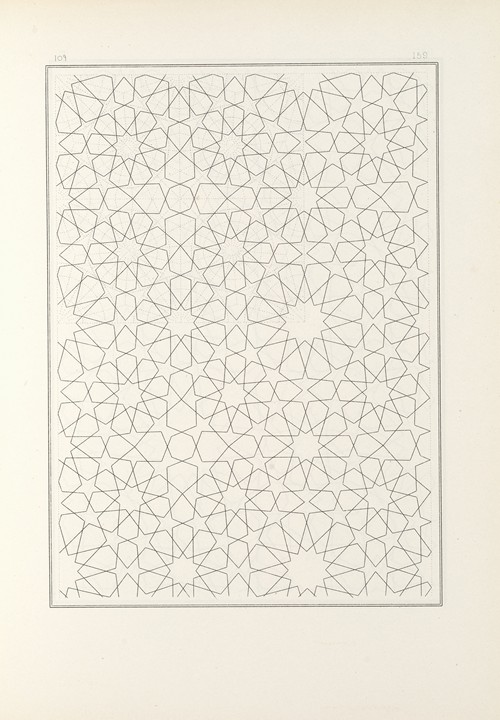

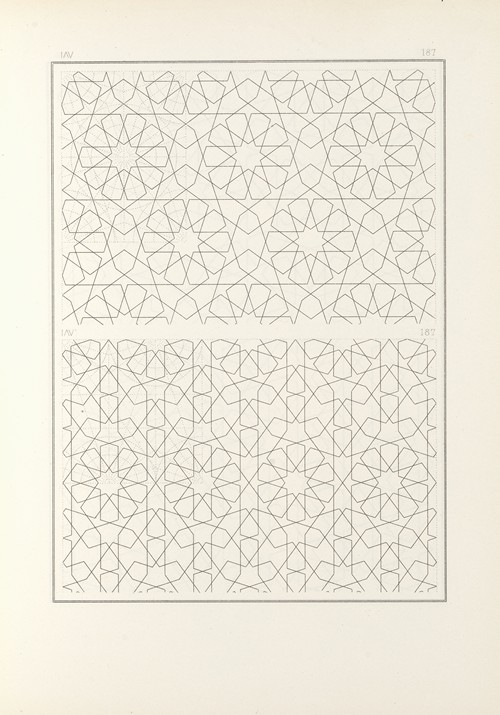

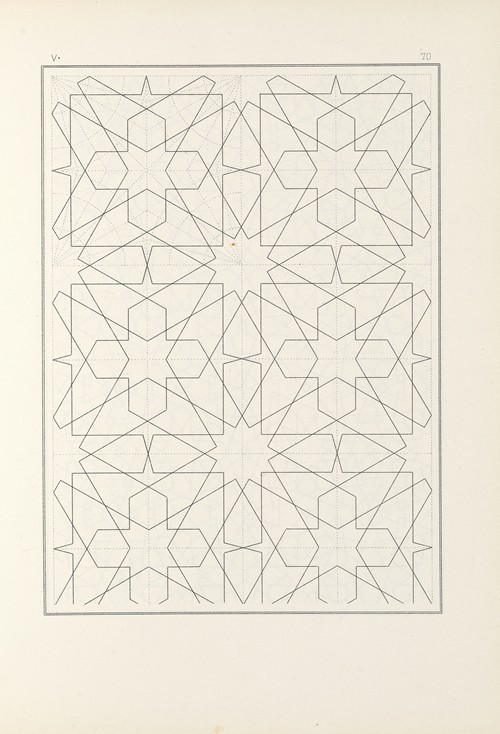

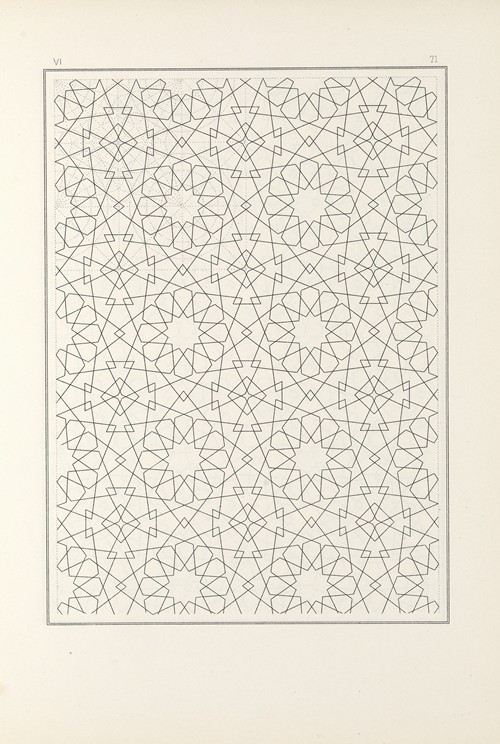

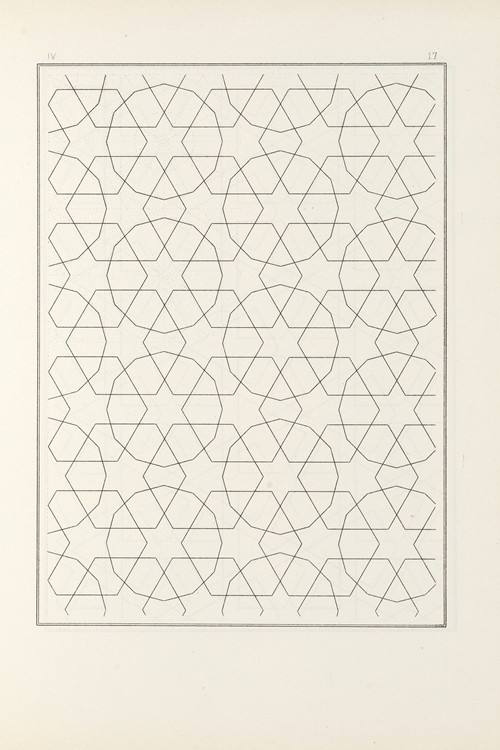

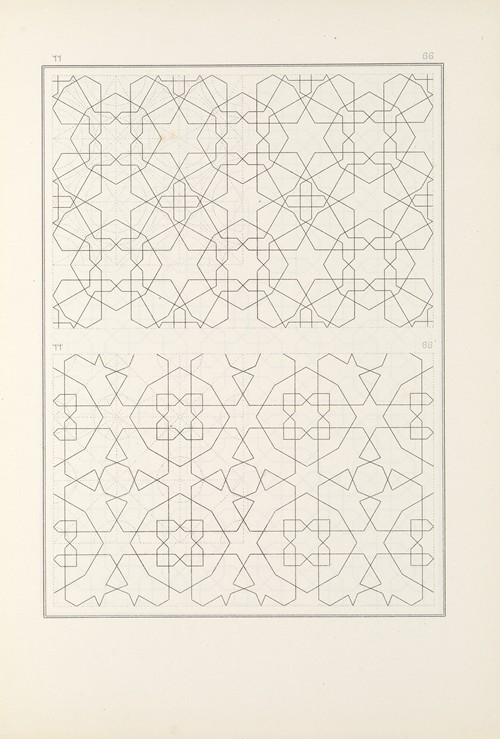

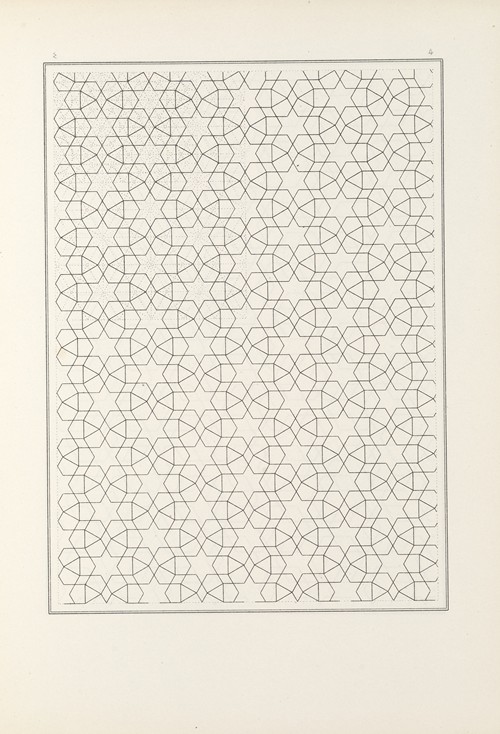

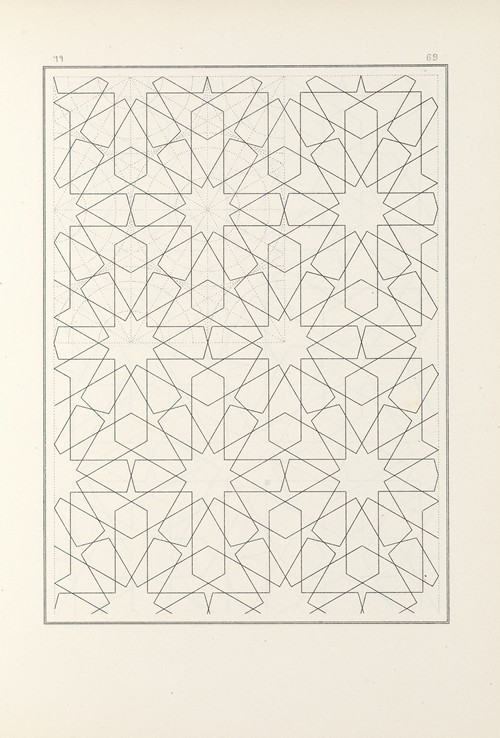

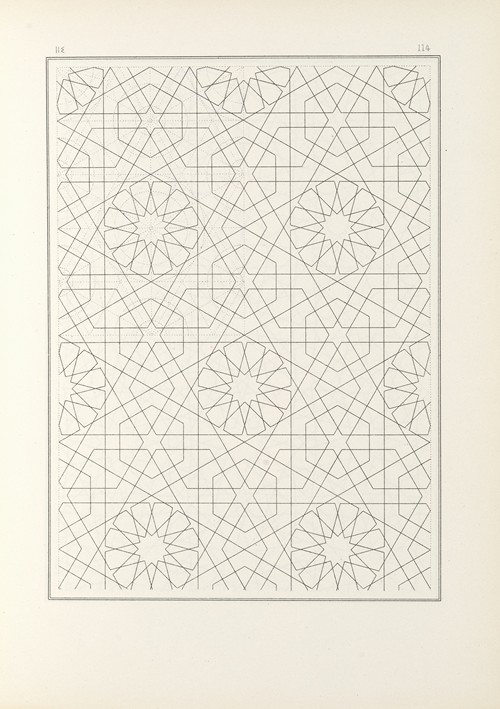

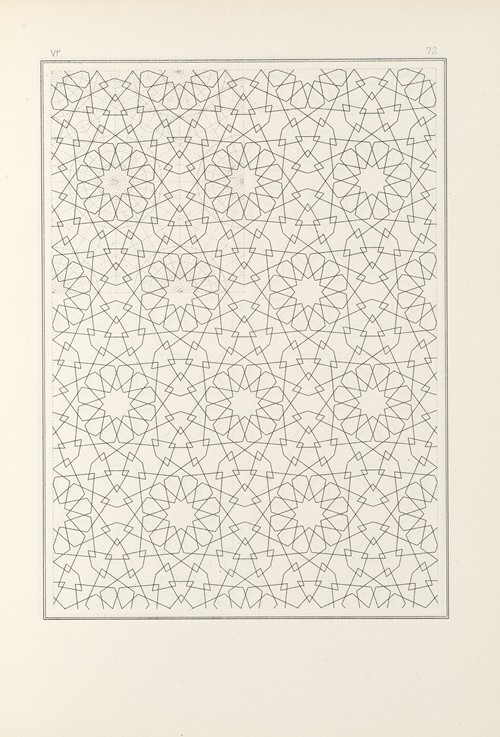

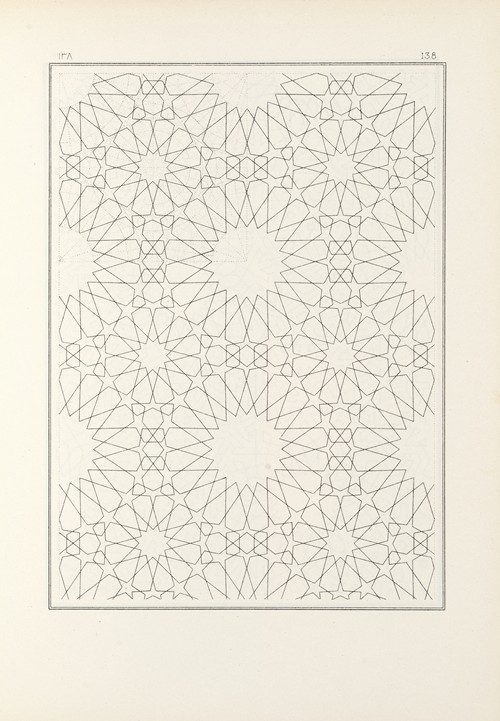

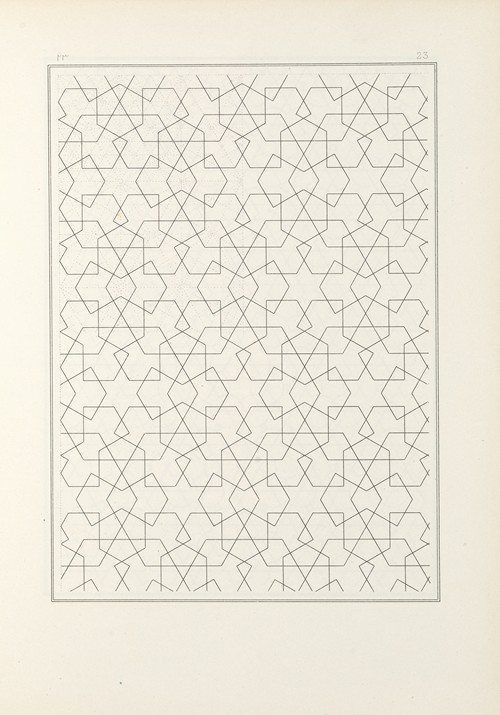

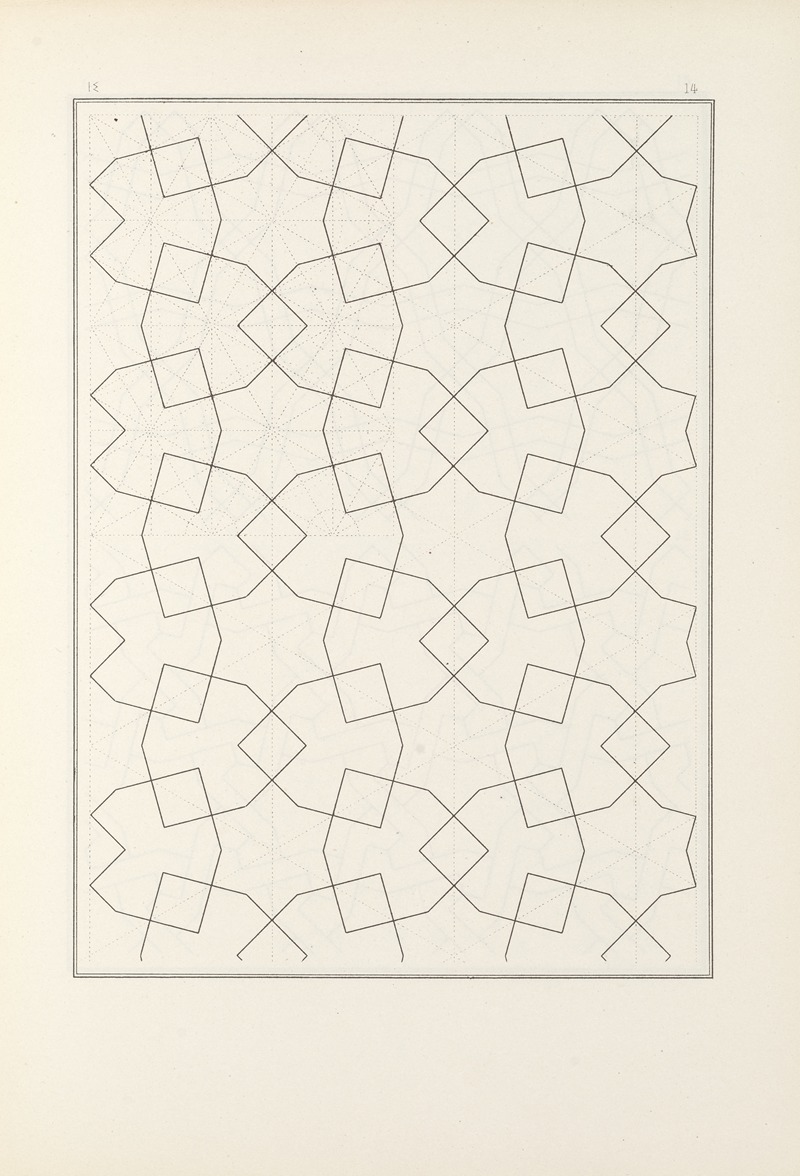

Born in Joigny (Yonne, Burgundy region) in 1838, and trained as an architect at the École des beaux-arts in Paris (though non-practicing), he spent several years, between 1863 and 1884, in the Near East, mainly in Egypt. Confronted by a world of forms and compositions unknown to him, he became fascinated by the way artists and craftsmen arranged geometrical forms, from the simplest to the most complex, interweaving their lines endlessly. Bourgoin, who had wanted to be a mathematician, understood that there was an underlying system to these compositions, and his driving ambition became to explain, through many concepts and drawings, the rules of the patterns.

Besides being fascinated by the geometry of forms, or aesthetic geometry, Bourgoin was an exceptional draftsman and his skills were widely recognized. During his stays in Egypt, Palestine, and Syria, he made thousands of pencil drawings, sketching the Islamic monuments of Alexandria, Cairo, Jerusalem and Damascus. His approach to the monuments was very specific; even if he had been authorized to enter the mosques, qubbats, madrasas, etc., he was not really attracted by picturesque views. His ambition was not to draw the monument or the building in its entirety, but to take note of the structure or decorative elements specific to Islamic art and architecture. This is why, when he draws a minaret in Cairo – an architectural feature that had always attracted the interest of Western travelers or artists – he pays close attention to the richly carved muqarnas used as corbelling for the minaret’s balcony. This is similarly true for the Sultan Qaytbay wikala complex and the sabil-kuttab at al-Azhar: Bourgoin is not interested in the small shops at the street level, but in the profusion of carved stones scattered across the façade, or the fine woodwork of the mashrabiyas. His drawing sheets are covered with small, delicate decorative elements.

In Cairo, a city he loved, he was impressed by the architectural majesty of the monuments, the use of geometrical design, the specific colors of the mosaic pavements and wall decoration, by the fantasy and invention of the mashrabiya-screens’ woodwork, and by the variety of decoration evident in mosque domes (qubbats). Once in Damascus in 1874–1875, where he had been sent to draw the main historical monuments of the city, especially the Umayyad mosque, he discovered the Ottoman patrician houses, with their overwhelming decoration composed from a great variety of materials – from marble, mother of pearl, mirrors, and color-pastes, to gold and silver – displaying bright colors and a profusion of vegetal and floral motifs. Back in France, he planned to publish a book on the Damascene houses, which sadly never materialised. The drawings he brought back, however, document his fascination.

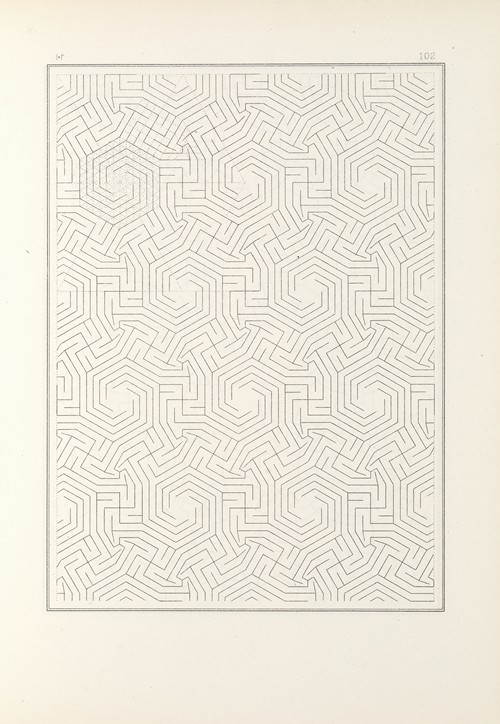

The other major aspect of Bourgoin’s work was the theoretical thinking he developed around the notion of ornament after returning from his first stay in Egypt. At the beginning, this was rooted in the parallel between the Western and Eastern historical and cultural approaches, but as time went by, Bourgoin’s thinking became more and more abstract, even abstruse, modified by the use of neologisms and the turn to philosophy and even psychology. Even more, his drawings too became completely abstract. Writing his theoretical volumes, a huge task, consumed Bourgoin’s vital energy.