Viscount Kuroda Seiki was a Japanese painter and teacher, noted for bringing Western art theory and practice to a wide Japanese audience. He was among the leaders of the yōga (or Western-style) movement in late 19th and early 20th-century Japanese painting, and has come to be remembered in Japan as "the father of Western-style painting."

Kuroda was born in Takamibaba, Satsuma Domain (present day Kagoshima Prefecture), as the son of a samurai of the Shimazu clan, Kuroda Kiyokane and his wife Yaeko. At birth, the boy was named Shintarō; this was changed to Seiki in 1877, when he was 11. In his personal life, he used the name Kuroda Kiyoteru, which uses an alternate pronunciation of the same Chinese characters.

Even before his birth, Kuroda had been chosen by his paternal uncle, Kuroda Kiyotsuna, as heir; formally, he was adopted in 1871, after traveling to Tokyo with both his birth mother and adoptive mother to live at his uncle's estate. Kiyotsuna was also a Shimazu retainer, whose services to Emperor Meiji in the Bakumatsu period and at the Battle of Toba–Fushimi led to his appointment to high posts in the new imperial government; in 1887 he was named a viscount. Because of his position, the elder Kuroda was exposed to many of the modernizing trends and ideas coming into Japan during the early Meiji period; as his heir, young Kiyoteru also learned from them and took his lessons to heart.

In his early teens, Kuroda began to learn the English language in preparation for his university studies; within two years, however, he had chosen to switch to French instead. At 17, he enrolled in pre-college courses in French, as preparation for his planned legal studies in college. Consequently, when in 1884 Kuroda's brother-in-law Hashiguchi Naouemon was appointed to the French Legation, it was decided that Kuroda would accompany him and his wife to Paris to begin his real studies of law. He arrived in Paris on March 18, 1884 and was to remain there for the next decade.

Kuroda had received painting lessons in his youth, and had been given a watercolor set by his adoptive mother as a present upon leaving for Paris, but he had never considered painting as anything more than a hobby. However, in February 1886 Kuroda was attending a party at the Japanese legation for Japanese nationals in Paris; here, he met the painters Yamamoto Hōsui and Fuji Masazō, as well as art dealer Tadamasa Hayashi, a specialist in ukiyo-e. All three urged the young student to turn to painting, saying that he could better help his country by learning to paint like a Westerner rather than learning law. Kuroda agreed, and began formally studying art at an art studio while simultaneously continuing his studies in law in an effort to please his adoptive father. This situation proved untenable, however, and Kuroda finally succeeded in convincing his father to allow him to abandon his legal studies and study painting full time. In May 1886, Kuroda entered the studio of Raphaël Collin, a noted Academic painter who had shown work in several Paris Salons. Kuroda also received guidance from Pierre Puvis de Chavannes, who influenced Kuroda's later use of the human body to represent abstract concepts.

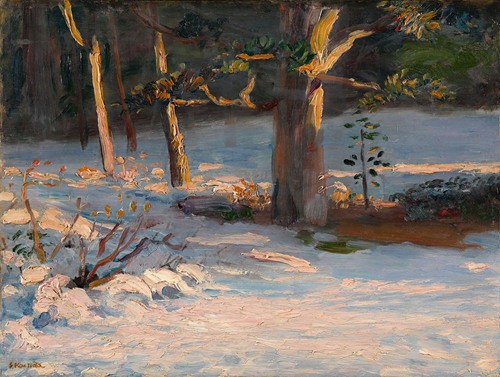

In 1886, Kuroda met another young Japanese painter, Kume Keiichiro, newly arrived in France, who also joined Collin's studio. The two became friends, and soon became roommates as well. It was during these years that he began to mature as a painter, first following the traditional course of study in Academic studio art before eventually also encountering plein-air painting. In 1890 Kuroda moved from Paris to the village of Grez-sur-Loing, an artists' colony about 70 kilometers south of Paris which had been formed by painters from the United States and from northern Europe. It was at Grez-sur-Loing that Kuroda first began to experiment with plein-air techniques, discovering inspiration in the rural landscape, as well as a young woman, Maria Billault, who became one of his favorite models.

In 1893, Kuroda returned to Paris and began work on his most important painting to date, Morning Toilette, which would later become the first nude painting to be publicly exhibited in Japan. This large-scale work, which was destroyed in World War II, was accepted with great praise by the Académie des Beaux-Arts; Kuroda intended to bring it with him to Japan to shatter the Japanese prejudice against the depiction of the nude figure. With the painting in hand, he set out for home via the United States, arriving in July 1893.

Having spent many long years of study in France to gain mastery of Western-style painting, Kuroda was eager to try out his newfound skills on the landscapes of his home country. Soon after arriving back in Japan, Kuroda traveled to Kyoto for the first time in his life, and used plein-air techniques to depict famous local sights, such as geisha and ancient temples. Paintings inspired by this trip include Maiko (1893, Tokyo National Museum) and Talk on Ancient Romance (1898, destroyed).

When Kuroda returned to Japan, the best-known society for Western-style painting was the Meiji Fine Art Society (Meiji Bijutsukai [ja]), which was strongly under the influence of European Academicism and the Barbizon School, which had been introduced to Japan by the Italian artist Antonio Fontanesi at the government-funded Technical Fine Arts School [it] (Kо̄bu Bijutsu Gakkо̄) beginning in 1876. Kuroda submitted several of his paintings to the Meiji Fine Arts Society's annual exhibition, which exhibited nine of his works in 1894. His innovative painting style, heavily influenced by the latest European plein air and Impressionist techniques, shocked Japanese audiences. For example, the art critic Takayama Chogyū wrote that anyone who found this type of painting beautiful must have "poor eyesight." However, many younger artists found Kuroda's innovative style inspiring and flocked to become his students. In particular, Kuroda's style of bright color tones emphasizing the changes of light and atmosphere was considered revolutionary. Kobayashi Mango, one of Kuroda's students from this time, recalled that when Kuroda returned to Japan, it was as if "those who had been groping along a wild dark path suddenly became aware of a single ray of brightness."

In 1894, Yamamoto Hōsui, one of the artists who had encouraged Kuroda to study art in France, handed over control of the art school he had founded, the Seikо̄kan (生巧館), to Kuroda, who inherited all of Yamamoto's students. Kuroda renamed the school Tenshin Dо̄jо̄ (天心道場) and remodeled its pedagogy to focus on Western precepts and plein-air painting.