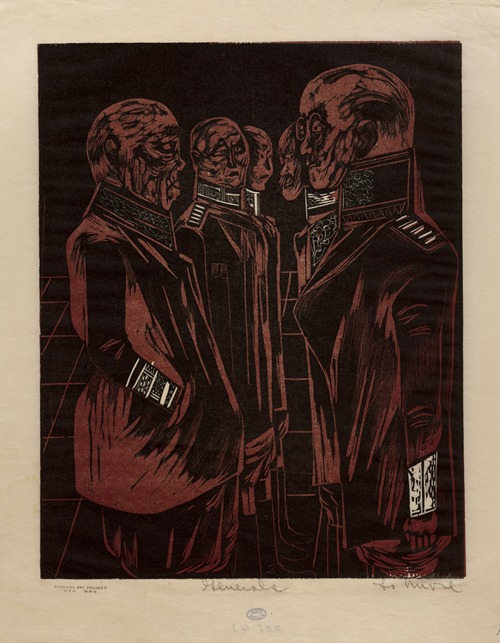

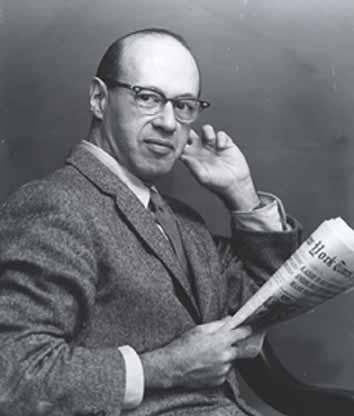

Joseph Hirsch was an American painter, illustrator, muralist and teacher. Social commentary was the backbone of Hirsch's art, especially works depicting civic corruption and racial injustice.

His works are in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Museum of Modern Art, the Whitney Museum of American Art, the Smithsonian American Art Museum, and many other museums.

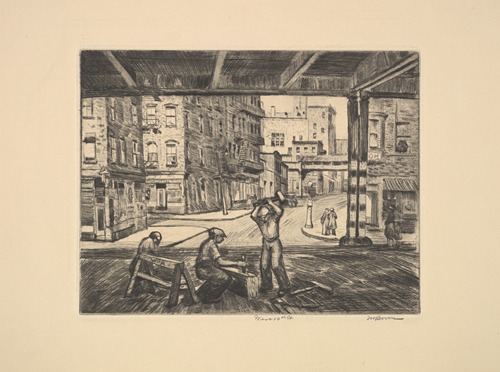

The son of physician Charles S. Hirsch and Fannie Wittenberg, he was of German-Jewish heritage and grew up in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Hirsch attended Philadelphia public schools and Central High School. At age 17, he entered the Pennsylvania Museum and School of Industrial Art (now the University of the Arts), where he was instructed in the Philadelphia realist tradition of Thomas Eakins. After graduation, he studied privately with George Luks in New York City (1932–33). Luks had been a founder of the Ashcan School and one of "The Eight," a group of painters who depicted everyday scenes of urban life. He introduced Hirsch to the Social Realism movement.

Following Luks's 1933 death, Hirsh studied further with Henry Hensche in Provincetown, Massachusetts (Summers 1934 & 1935). A 1935 Woolley Fellowship from the Institute of International Education enabled him to travel throughout Europe for more than a year, and he returned to the United States in November 1936, by way of Egypt, Asia and the Pacific Ocean.

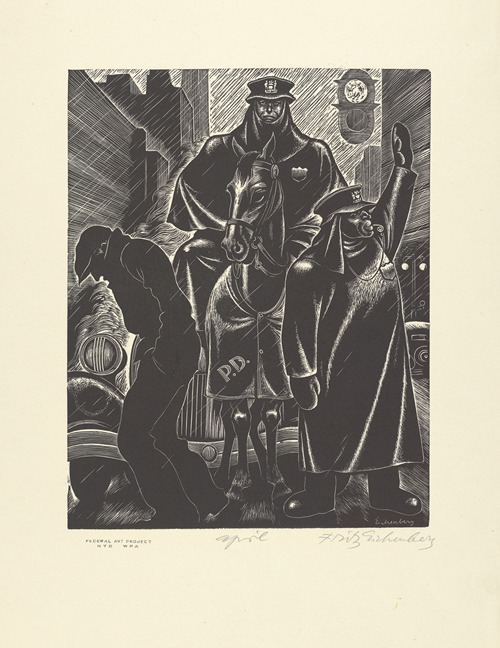

In the late 1930s, Hirsch worked in Philadelphia as an artist in the easel painting division of the Works Project Administration. He painted murals for the Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America Office Building at 2113-27 South Street; for the Family Court Building at 1801 Vine Street; and for the Benjamin Franklin High School at Broad & Green Streets (now demolished).

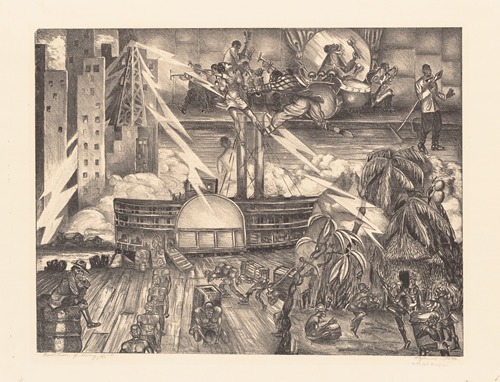

During World War II, his image of a smiling and waving soldier shipping out, Till We Meet Again (1942), was the most popular War Bond poster. In 1942–1943, he was embedded as an artist/war correspondent with naval airmen in Florida, then with the U.S. Navy Medical Corps in the South Pacific. In 1944, he was embedded with the U.S. Army Medical Corps in North Africa and Italy. Some of his most powerful war paintings depict wounded soldiers being removed from the battlefield.

The three trips I went on had to do with naval air training at Pensacola, Florida; then naval medicine in the Pacific; and army medicine in Italy and North Africa. It was hard and unforgettable and lonely and sometimes frustrating running into the real McCoy. I was of course moved most by the two medical assignments because I saw wounded kids. It was a very good experience. You know, talking with — I saw soldiers in more hospitals — I had been in many hospitals in Philadelphia as my father was a doctor. I also visited a hospital ship. To see the kind of organized spirit of cooperation was — I don't know what the Navy's Medical Corps is like now, but at that time during the war to see a lot of wonderful improvisation made for material for good sketching and painting and drawing. The majority of the work was done immediately upon my return. I'd go out for a couple of months and come back and spend another three or four months doing perhaps a dozen paintings and as many drawings both for the aviation series and the naval medicine, and the Army medical.

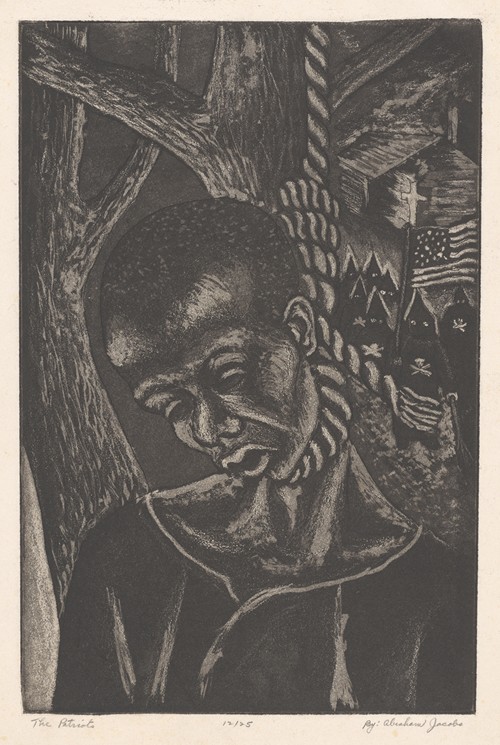

Hirsh often used an intimate scene to suggest the enormous emotion of a subject: The Lynch Family (1946) depicts a young black mother holding a baby, distraught at the murder of her husband. The painting was published as an illustration in the Communist journal The New Masses, following the July 1946 lynching of two black men and their wives in Monroe, Georgia. The Burden (1947) depicts an overwhelmed American GI installing white cross gravemarkers in a military cemetery, while in the background a second GI unloads yet another jeep-full. Hirsch's poster for the original 1949 Broadway production of Arthur Miller's Death of a Salesman depicts a beaten-down Willy Loman trudging onward with his heavy suitcases.

Hirsch occasionally explored Christian themes. His version of The Crucifixion (1945) is a closeup view from behind, and focuses on the busy workman preparing to nail Jesus's hand to the cross. The Journey (ca.1948), painted as a Christmas card for Hallmark Cards, depicts the Flight into Egypt, and presents Mary and Joseph in modern dress on the back of a donkey—with Joseph holding a trombone! Supper (1963–1964) depicts 12 vagrant men seated around a table in what appears to be a soup kitchen. The painting's name and the number of men recall The Last Supper.

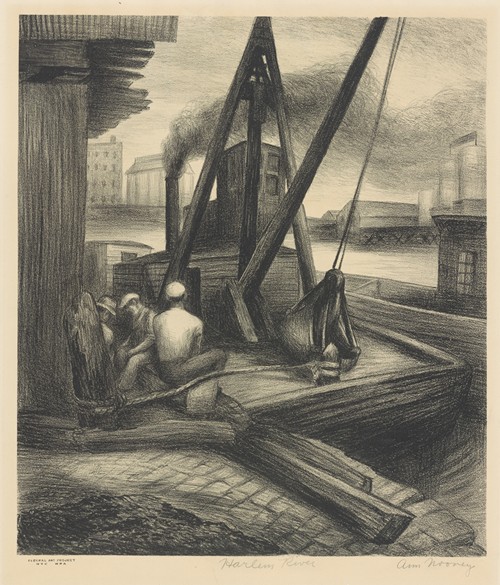

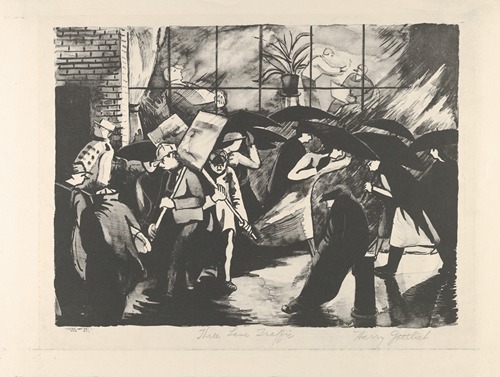

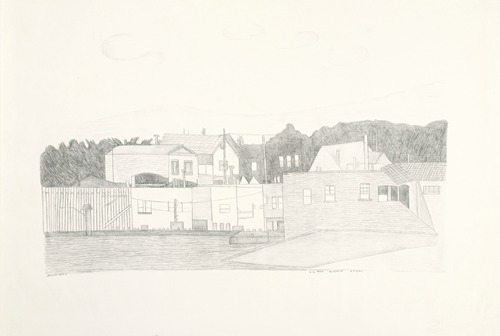

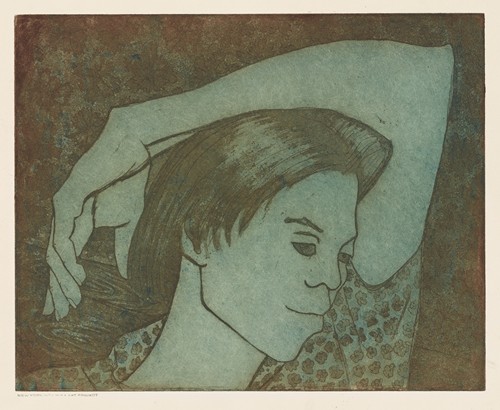

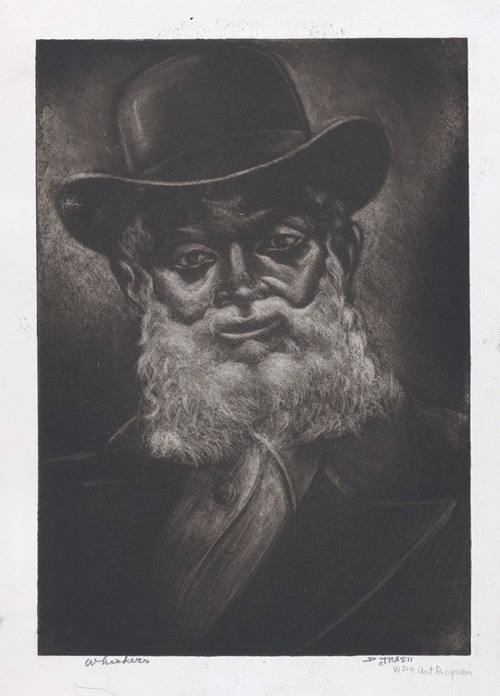

Hirsch also worked as a commercial artist and portrait painter. He produced dozens of lithographs, most based on his paintings, and described himself as a "full-time painter and a Sunday lithographer." Among his popular lithographs were Lunch Hour (1942), depicting a black youth asleep at his school desk; Banquet (1945), a closeup of a black man and an old white man sitting side by side at a lunch counter; and a color lithograph of the Boston Tea Party, published at the time of the 1976 Bicentennial. The U.S. Bureau of Reclamation commissioned him in the late-1960s to create illustrations documenting construction of the Soldier Creek Dam (completed 1974), in Wasatch County, Utah.

In his mature period, the 1960s and 1970s, Hirsch used a series of layered planes to compose a painting. Typically, these planes were parallel to the picture plane, with depth suggested by receding figures, rather than through lines of perspective. These paintings appear to be snapshots, capturing people in mid-action, not posing.

Hirsch taught at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago (1947–1948), the American Art School of New York University (1948–1949), the National Academy of Design (1959–1967), and the Art Students League of New York (1967–1981). He was an artist-in-residence at the University of Utah (Summer 1959, 1975), Utah State University (year), Dartmouth College (Spring 1966), and Brigham Young University (1971).

Hirsch was a founding member of Artists Equity, an organization modeled on Actors Equity, created to protect the rights of visual artists. It began in New York City in 1949, and grew to have chapters in dozens of U.S. cities. Hirsch was awarded a Fulbright Fellowship to study and work in Paris for a year, and he and his family arrived in France in September 1949. Even prior to Senator Joseph McCarthy's notorious February 1950 declaration that hundreds of known Communists were working in the U.S. State Department, the political climate in the United States was becoming hostile to those holding leftist views. Hirsch's Fulbright was renewed, but, as the end of its second year approached, he sold his house on Cape Cod to extend his family's stay in Paris. Congressman George Anthony Dondero denounced Artists Equity as a front organization for Communists in a March 17, 1952 speech delivered on the floor of the U.S. House of Representatives—"Communist Conspiracy in Art Threatens American Museums." A number of Artists Equity member artists were blacklisted. Expatriate Hirsch was later denounced as a Communist sympathizer, and public pressure was put on the Dallas Museum of Art to remove his award-winning Nine Men (1949) from an exhibition. Instead, the museum moved Nine Men, a painting by Diego Rivera, and one by George Grosz into a separate room, and asked museumgoers to judge the Communist influence for themselves. The Hirschs did not return to the United States until 1955.