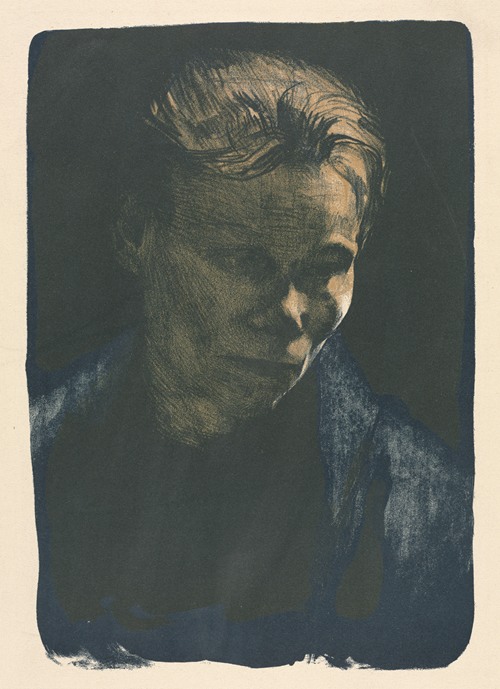

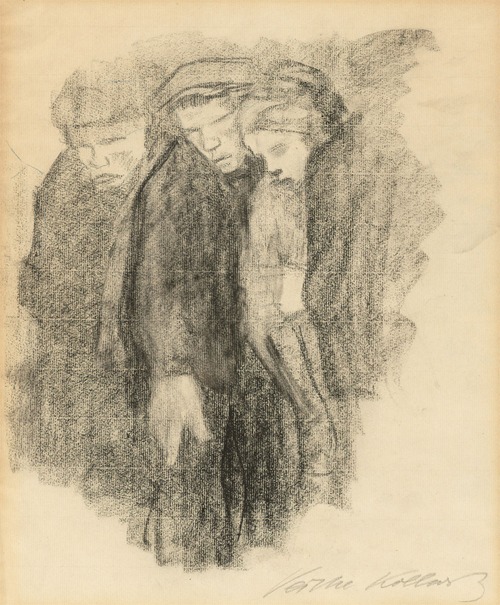

Käthe Kollwitz was a German artist who worked with painting, printmaking (including etching, lithography and woodcuts) and sculpture. Her most famous art cycles, including The Weavers and The Peasant War, depict the effects of poverty, hunger and war on the working class. Despite the realism of her early works, her art is now more closely associated with Expressionism. Kollwitz was the first woman to not only be elected to the Prussian Academy of Arts but to also receive honorary professor status.

Kollwitz was born in Königsberg, Prussia, the fifth child in her family. Her father, Karl Schmidt, was a radical Social democrat who became a mason and house builder. Her mother, Katherina Schmidt, was the daughter of Julius Rupp, a Lutheran pastor who was expelled from the official Evangelical State Church and founded an independent congregation. Her education and her art were greatly influenced by her grandfather's lessons in religion and socialism.

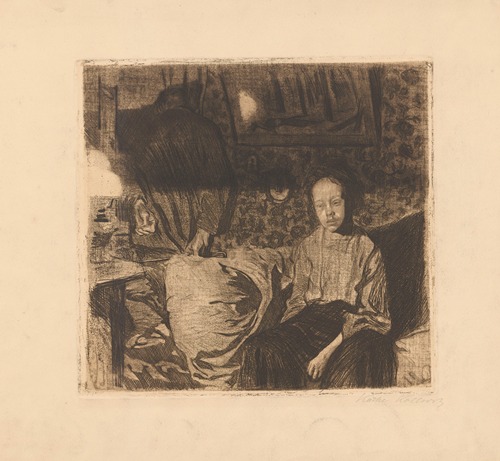

Recognizing her talent, Kollwitz's father arranged for her to begin lessons in drawing and copying plaster casts when she was twelve. At sixteen she began working with subjects associated with the Realism movement, making drawings of working people, sailors and peasants she saw in her father's offices. Wishing to continue her studies at a time when no colleges or academies were open to young women, Kollwitz enrolled in an art school for women in Berlin. There she studied with Karl Stauffer-Bern, a friend of the artist Max Klinger. The etchings of Klinger, their technique and social concerns, were an inspiration to Kollwitz.

In 1888, she went to Munich to study at the Women's Art School, where she realized her strength was not as a painter, but a draughtsman. At the age of seventeen, her brother Konrad introduced her to Karl Kollwitz, a medical student, then thereafter Kathe became engaged to Karl, while she was studying art in Munich. In 1890, she then returned to Königsberg, rented her first studio, and continued to depict the harsh labors of the working class. These subjects had become an inspiration in her work for years.

In 1891, Kollwitz married Karl, by this time a doctor tending to the poor in Berlin, where the couple moved into the large apartment that would be Kollwitz's home until it was destroyed in World War II.

It is believed Kollwitz suffered anxiety during her childhood due to the death of her siblings, including the early death of her younger brother, Benjamin. More recent research suggests that Kollwitz may have suffered from a childhood neurological disorder dysmetropsia (sometimes called Alice in Wonderland syndrome, due to its sensory hallucinations and migranes).

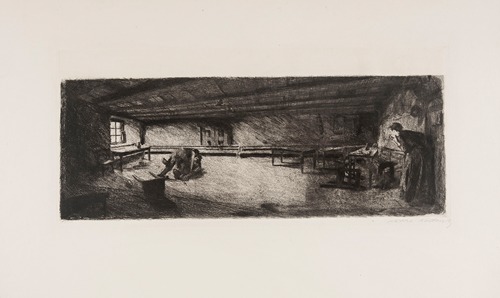

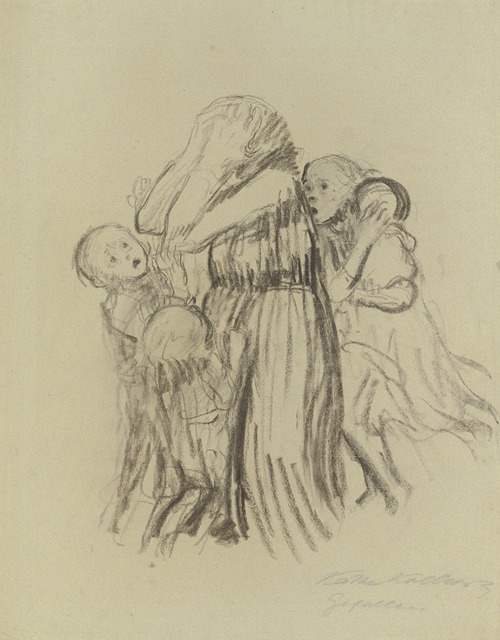

Between the births of her sons – Hans in 1892 and Peter in 1896 – Kollwitz saw a performance of Gerhart Hauptmann's The Weavers, which dramatized the oppression of the Silesian weavers in Langenbielau and their failed revolt in 1844. Kollwitz was inspired by the performance and ceased work on a series of etchings she had intended to illustrate Émile Zola's Germinal. She produced a cycle of six works on the weavers theme, three lithographs (Poverty, Death, and Conspiracy) and three etchings with aquatint and sandpaper (March of the Weavers, Riot, and The End). Not a literal illustration of the drama, nor an idealization of workers, the prints expressed the workers' misery, hope, courage, and eventually, doom.

The cycle was exhibited publicly in 1898 to wide acclaim. But when Adolph Menzel nominated her work for the gold medal of the Große Deutsche Kunstausstellung in Berlin, Kaiser Wilhelm II withheld his approval, saying "I beg you gentlemen, a medal for a woman, that would really be going too far . . . orders and medals of honour belong on the breasts of worthy men." Nevertheless, The Weavers became Kollwitz' most widely acclaimed work.

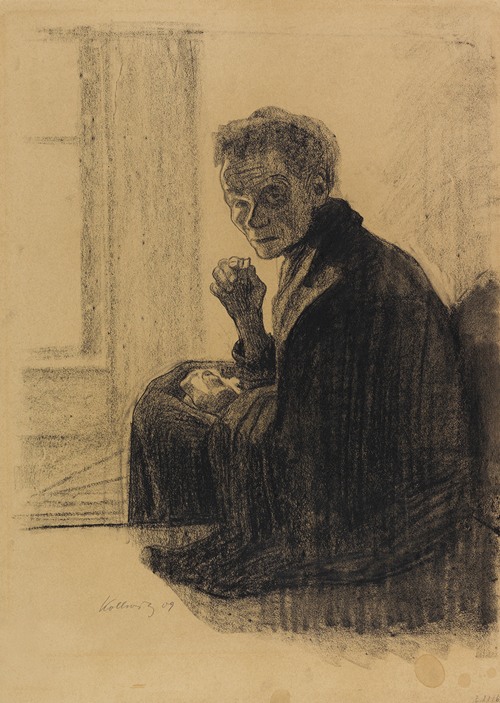

Kollwitz's second major cycle of works was the Peasant War. The culmination of this series spanned from 1902 to 1908 due to many preliminary drawings and discarded ideas in lithography. The German Peasants' War was a violent revolution in Southern Germany in the early years of the Reformation. Beginning in 1525, peasants who had been treated as slaves took arms against feudal lords and the church. Similar to The Weavers, this body of work might have been influenced by a Hauptmann drama, Florian Geyer. However, the initial source of Kollwitz's interest dated to her youth when she and her brother Konrad playfully imagined themselves as barricade fighters in a revolution. Not only did Kollwitz have a childhood connection, but an artistic connection as well. She was an advocate for those without a voice and liked to portray the working class in a way no one else saw. The artist identified with the character of Black Anna, a woman cited as a protagonist in the uprising. When completed, the Peasant War consisted of etchings, aquatints, and soft grounds: Plowing, Raped, Sharpening the Scythe, Arming in the Vault, Outbreak, The Prisoners and After the Battle. After the Battle is described as eerily premonitory as it features a mother searching through corpses in the night, looking for her son. In all, the works were technically more impressive than those of The Weavers, owing to their greater size and dramatic command of light and shadow. They are Kollwitz's highest achievements as an etcher.

Kollwitz visited Paris twice while working on Peasant War and enrolled in classes at the Académie Julian in order to learn how to sculpt. The etching Outbreak was awarded the Villa Romana prize. This prize provided a year's stay in 1907 in a studio in Florence. Although Kollwitz completed no work during her stay, she later recalled the impact of early Renaissance art she experienced during her time residing in Florence.

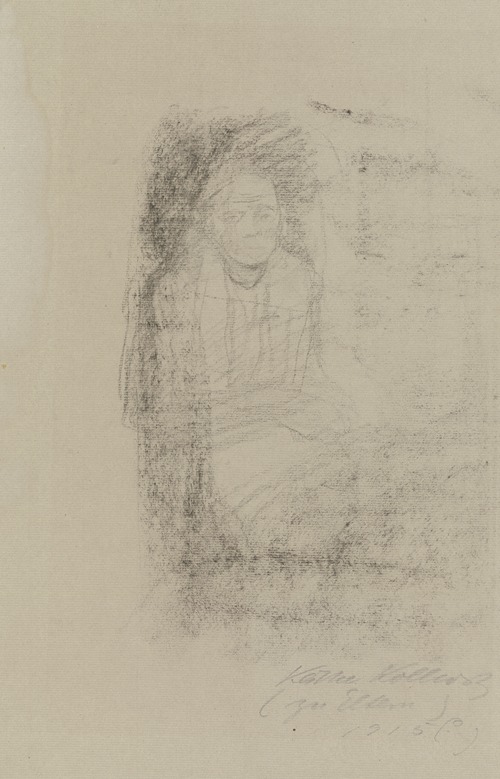

After her return to Germany, Kollwitz continued to exhibit her work but was impressed by younger compatriots. Expressionists and Bauhaus artists inspired Kollwitz to simplify her means of expression. Subsequent works such as Runover, 1910, and Self-Portrait, 1912, show this new direction. She also continued to work on sculpture.

Kollwitz lost her younger son, Peter, on the battlefield in World War I in October 1914. The loss of her child began a stage of prolonged depression in her life. By the end of 1914 she had made drawings for a monument to Peter and his fallen comrades. She destroyed the monument in 1919 and began again in 1925. The memorial, titled The Grieving Parents, was finally completed and placed in the Belgian cemetery of Roggevelde in 1932. Later, when Peter's grave was moved to the nearby Vladslo German war cemetery, the statues were also moved.

Kollwitz was a committed socialist and pacifist, who was eventually attracted to communism. She expressed her political and social sympathies in her woodcut print, "memorial sheet for Karl Liebknecht" and in her involvement with the Arbeitsrat für Kunst, a part of the Social Democratic Party government in the first few weeks after the war. As the war wound down and a nationalistic appeal was made for old men and children to join the fighting, Kollwitz implored in a published statement:

There has been enough of dying! Let not another man fall!

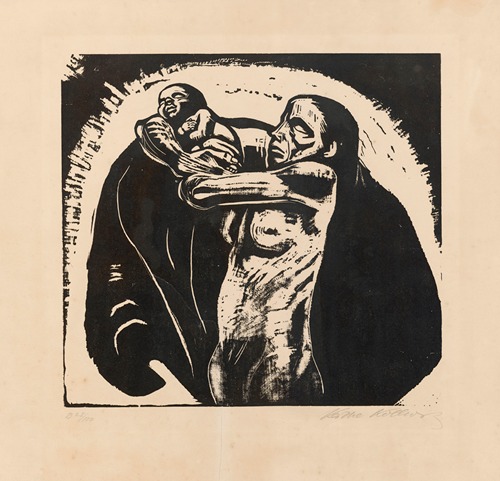

While working on the sheet for Karl Liebknecht, she found etching insufficient for expressing monumental ideas. After viewing woodcuts by Ernst Barlach at the Secession exhibitions, she completed the Liebknecht sheet in the new medium and made about 30 woodcuts by 1926.

In 1920 Kollwitz was elected a member of the Prussian Academy of Arts, the first woman to be so honored. Membership entailed a regular income, a large studio, and a full professorship.

In 1928 she was also named director of the Master Class for Graphic Arts at the Berlin Academy. However, this title would soon be stripped after the Nazi regime rose to power.

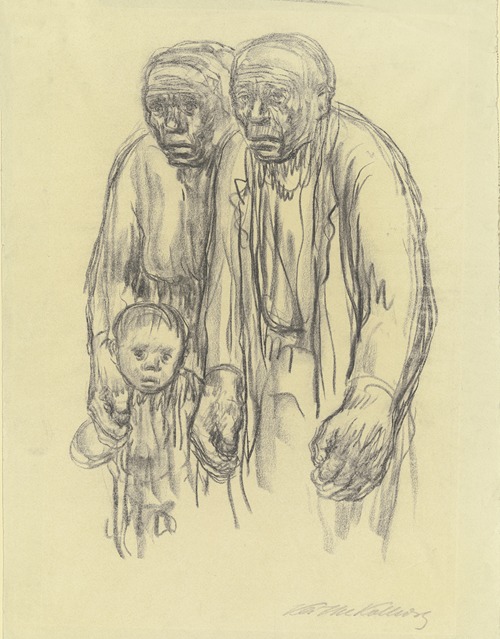

In the years after World War I, her reaction to the war found a continuous outlet. In 1922–23 she produced the cycle War in woodcut form, including the works The Sacrifice, The Volunteers, The Parents, The Widow I, The Widow II, The Mothers, and The People. Much of this art was inspired by pro-war propaganda which she and Otto Dix riffed on to create anti-war propaganda. Kollwitz wanted to show the horrors of living through a war to combat the pro-war sentiment that had begun to grow in Germany again. In 1924 she finished her three most famous posters: Germany's Children Starving, Bread, and Never Again War.

Working now in a smaller studio, in the mid-1930s she completed her last major cycle of lithographs, Death, which consisted of eight stones: Woman Welcoming Death, Death with Girl in Lap, Death Reaches for a Group of Children, Death Struggles with a Woman, Death on the Highway, Death as a Friend, Death in the Water, and The Call of Death.

When Richard Dehmel called for more soldiers to fight in World War I in 1918, Kollwitz wrote an impassioned letter to the newspaper he published his call in stating that there should be no more war, and that "seed corn must not be ground" in reference to young soldiers who were dying in the war. In 1942, she made a piece by the same name, this time in reaction to World War II. The work shows a mother, arms cast over three young children to protect them.

In 1933, after the establishment of the National-Socialist regime, the Nazi Party authorities forced her to resign her place on the faculty of the Akademie der Künste following her support of the Dringender Appell. Her work was removed from museums. Although she was banned from exhibiting, one of her "mother and child" pieces was used by the Nazis for propaganda.

“They give themselves with jubilation; they give themselves like a bright, pure flame ascending straight to heaven.”

In July 1936, she and her husband were visited by the Gestapo, who threatened her with arrest and deportation to a Nazi concentration camp; they resolved to commit suicide if such a prospect became inevitable. However, Kollwitz was by now a figure of international note, and no further action was taken.

On her 70th birthday, she "received over 150 telegrams from leading personalities of the art world," as well as offers to house her in the United States, which she declined for fear of provoking reprisals against her family.

She outlived her husband (who died from an illness in 1940) and her grandson Peter, who died in action in World War II two years later.

She was evacuated from Berlin in 1943. Later that year, her house was bombed and many drawings, prints, and documents were lost. She moved first to Nordhausen, then to Moritzburg, a town near Dresden, where she lived her final months as a guest of Prince Ernst Heinrich of Saxony. Kollwitz died just 16 days before the end of the war.