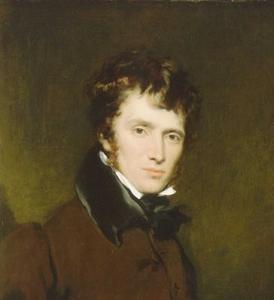

Clarkson Frederick Stanfield was a prominent English painter (often inaccurately credited as William Clarkson Stanfield) who was best known for his large-scale paintings of dramatic marine subjects and landscapes. He was the father of the painter George Clarkson Stanfield and the composer Francis Stanfield.

Stanfield was born in Sunderland, the son of James Field Stanfield (1749–1824) an Irish-born author, actor and former seaman, and Mary Hoad, an artist and actress. Stanfield was likely to have inherited artistic talent from his mother, who is said to have been an accomplished artist, but died in 1801. His father remarried, to Maria Kell, a year later. Stanfield was named after Thomas Clarkson, the slave trade abolitionist, whom his father knew, and this was the only forename he used, although there is reason to believe Frederick was a second one.

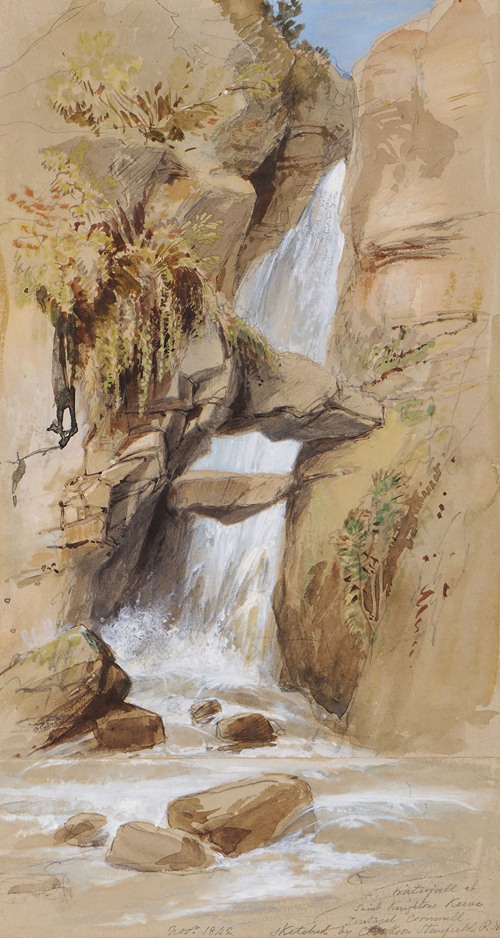

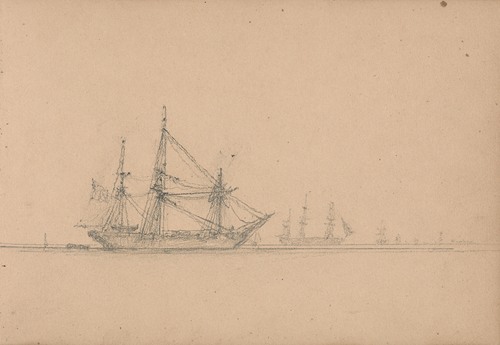

He was briefly apprenticed to a coach decorator in 1806, but left owing to the drunkenness of his master's wife and joined a South Shields collier to become a sailor. In 1808 he was pressed into the Royal Navy, serving in the guardship HMS Namur at Sheerness. Discharged on health grounds in 1814, he then made a voyage to China in 1815 on the East Indiaman Warley and returned with many sketches.

An accident forced Stanfield to leave active service, but during his voyages he had acquired considerable skill as a draughtsman. In August 1816 Stanfield was engaged as a decorator and scene-painter at the Royalty Theatre in Wellclose Square, London. Along with David Roberts he was afterwards employed at the Coburg theatre, Lambeth, and in 1823 he became a resident scene-painter at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, where he rose rapidly to fame through the huge quantity of spectacular scenery and (moving) dioramas which he produced for that house until 1834.

Stanfield abandoned scenery painting after Christmas 1834, though he made exceptions for two personal friends: he designed scenery for the stage productions of William Charles Macready, and for the amateur theatricals of Charles Dickens.

Stanfield partnered with David Roberts in several large-scale diorama and panorama projects in the 1820s and 1830s. The newest development in these popular entertainments was the "moving diorama" or "moving panorama." These consisted of huge paintings that unfolded upon rollers like giant scrolls; they were supplemented with sound and lighting effects to create a nineteenth-century anticipation of cinema. Stanfield and Roberts produced eight of these entertainments; in light of their later accomplishments as marine painters, their panoramas of two important naval engagements, the Bombardment of Algiers and The Battle of Navarino, are worth noting.

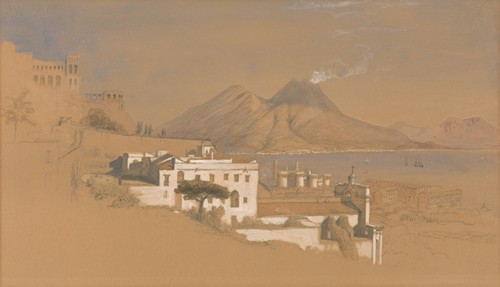

An 1830 tour through Germany and Italy furnished Stanfield with material for two more moving panoramas, The Military Pass of the Simplon (1830) and Venice and Its Adjacent Islands (1831). Stanfield executed the first in only eleven days; it earned him a fee of £300. The Venetian panorama of the next year was 300 feet long and 20 high; gas lit, it unrolled through 15 or 20 minutes. The show included stage props and even singing gondoliers. After the show closed, portions of the work were re-used in productions of Shakespeare's The Merchant of Venice and Otway's Venice Preserved.

The moving panoramas of Stanfield and other artists became highlights of the traditional Christmas pantomimes.

Meanwhile, Stanfield developed his skills as an easel painter, especially of marine subjects; he first exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1820 and continued, with only a few early interruptions, to his death. He was also a founder member of the Society of British Artists (from 1824) and its president for 1829, and exhibited there and at the British Institution, where in 1828 his picture Wreckers off Fort Rouge gained a premium of 50 guineas.

He was elected Associate Member of the Royal Academy in 1832, and became a full Academician in February 1835. His elevation was in part a result of the interest of William IV who, having admired his St. Michael's Mount at the Academy in 1831 (now in the National Gallery of Victoria, Australia), commissioned two works from him of the Opening of New London Bridge (1832) and The Entrance to Portsmouth Harbour. Both remain in the Royal Collection.

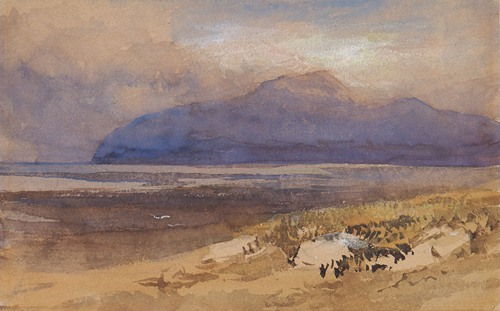

Until his death he contributed a long series of powerful and highly popular works to the Academy, both of marine subjects and landscapes from his travels at home and in France, the Netherlands, Germany, Italy, Spain, and Ireland.

Stanfield's art was powerfully influenced by his early practice as a scene-painter. But, though there is always a touch of the spectacular and the scenic in his works, and though their colour is apt to be rather dry and hard, they are large and effective in handling, powerful in their treatment of broad atmospheric effects and telling in composition, and they evince the most complete knowledge of the artistic materials with which their painter deals.

In his last 10 years, Stanfield's health deteriorated. He died in Hampstead, London, on 18 May 1867; there was an unfinished painting on his easel and a previous work, A Skirmish off Heligoland, hanging in a Royal Academy exhibition. He was buried in Kensal Green Catholic Cemetery.

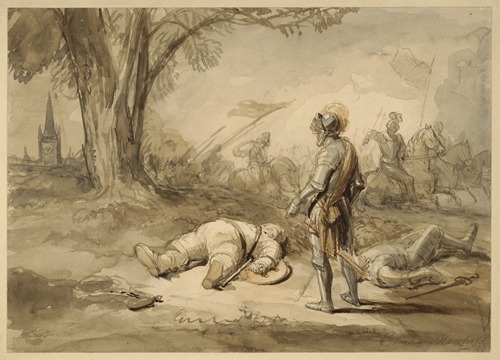

![A midsummer night’s dream, Snout; ‘Oh Bottom thou art changed …’ [III, 1]](https://mdl.artvee.com/ft/86751dr.jpg)