Maksimilian Voloshin was a Russian poet. He was one of the significant representatives of the symbolist movement in Russian culture and literature. He became famous as a poet and a critic of literature and the arts, being published in many contemporary magazines of the early 20th century, including Vesy, Zolotoye runo ('The Golden Fleece'), and Apollon. He was known for his translations of a number of French poetic and prose works into Russian.

Voloshin was born in Kiev in 1877. He spent his early childhood in Sevastopol and Taganrog. Reportedly, "his schooling included a few years at the Polivanov establishment and a school in the Crimea, where in 1893 his mother had bought a cheap plot of land at Koktebel." After secondary school, Voloshin entered Moscow University during "a time of the resurgence of the radical student movement in Russia." Voloshin reportedly actively participated in it, "which resulted in his expulsion from the University in 1899."

Not discouraged, Voloshin "resumed his travels the length and breadth of Russia, often on foot." In 1900, he worked with an expedition surveying the route of the Orenburg-Tashkent Railway.

Upon his return to Moscow, Voloshin did not seek reinstatement at the university, but continued his travels to such places as Western Europe, Greece, Turkey, and Egypt. Reportedly, "his stay in Paris and travels all over France had a particularly deep effect on" him and he came back to Russia "a veritable Parisian." While during this time in Russia there were "numerous literary groups and trends, known as the Silver Age," Voloshin remained aloof despite "being a close friend of many outstanding cultural figures of the day". In verses devoted to Valery Bryusov he wrote: "In your world, I am a passerby, close to all and yet a stranger to all."

When "a madman" ripped Repin's famous canvas Ivan the Terrible Killing His Son with a knife, shocking Intellectual Russia, Voloshin was the only person in the country to defend the man, "indicating that it was an esthetic statement appropriate to the painting, which displayed gore and bad taste". Voloshin had a brief affair with Miss Sabashnikova, but they soon broke up, and this had a profound effect on his work. Gradually, Voloshin was drawn back to Koktebel in the Crimea, where he had spent much of his childhood. His first collection of poetry appeared in 1910, soon followed by others. His collected essays were published in 1914.

During the years of the First World War, Voloshin, in Switzerland at the time, showed himself to be an author of profoundly insightful poems, engaging in a philosophically- and historically-based exploration of the tragic events of his contemporary Russia. He was known for his humanism, appealing "in the days of revolutions to be a human, not a citizen" and "in the disturbances of wars to realize the oneness. To be not a part, but all: not from one side, but from both."

Eventually Voloshin made it back to France, where he stayed until 1916. A year before the February Revolution in Russia, Voloshin returned to his home country and settled in Koktebel. He would live there until the end of his life. The ensuing Civil War prompted Voloshin to write long poems linking what was happening in Russia to its distant, mythologized past. Later, Voloshin would be accused of the worst sin in the Soviet ideologue's book: keeping aloof from the political struggle between Reds and Whites. In fact, he tried to protect the Whites from the Reds and the Reds from the Whites. His house, today a museum, still has a clandestine niche in which he hid people whose lives were in danger.

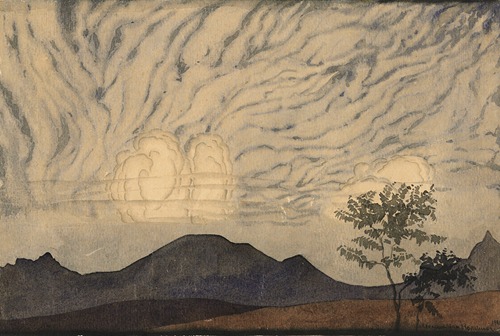

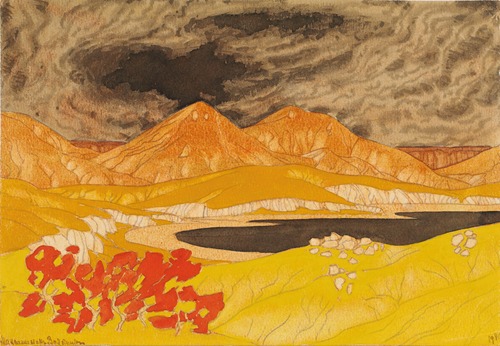

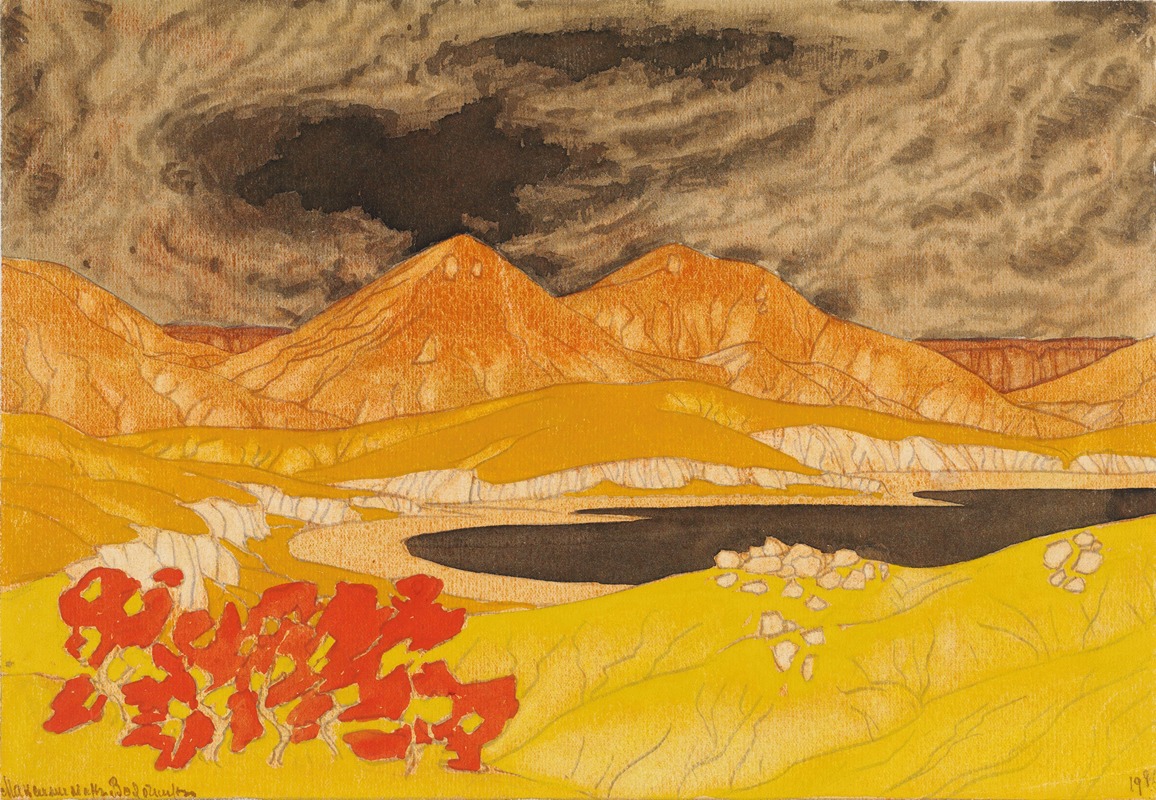

Reportedly, "never were a poet's works so closely bound up with the place where he lived. He recreated the semi-mythical world of the Cimmerii in pictures and verses. He painted landscapes of primeval eastern Crimea. Nature itself seemed to respond to Voloshin's art. If one looks west from the Voloshin Museum, there is a mountain whose shape is uncannily similar to Voloshin's profile."

Miraculously, Voloshin survived the Civil War, and in the 1920s set up a free rest home for writers in his house, in accordance with his rejection of private property. Yet he continued to draw most of his inspiration from solitude and contemplation of nature.

During the latter years of his life, he gained additional recognition as a subtle water-colour painter. Many of his art works now belong to museums around the world, while others are kept in private collections in Russia and abroad.