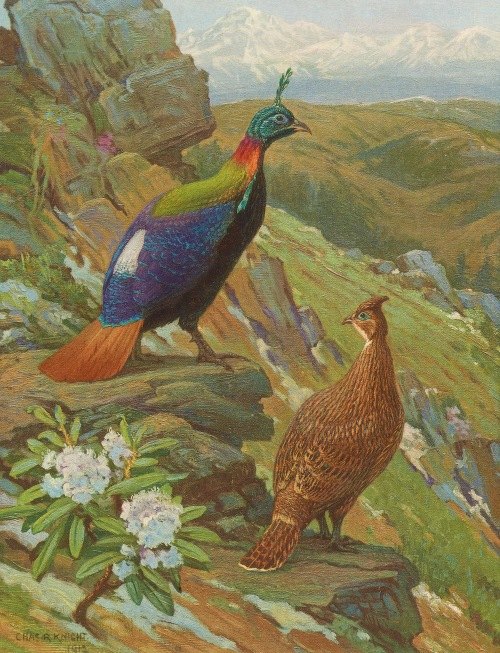

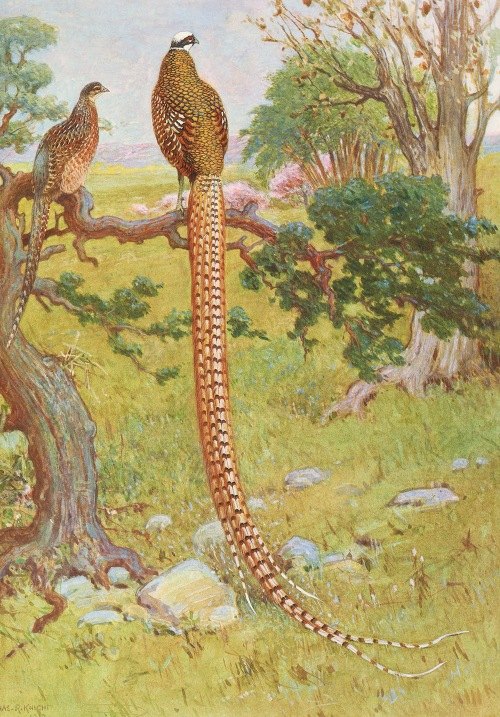

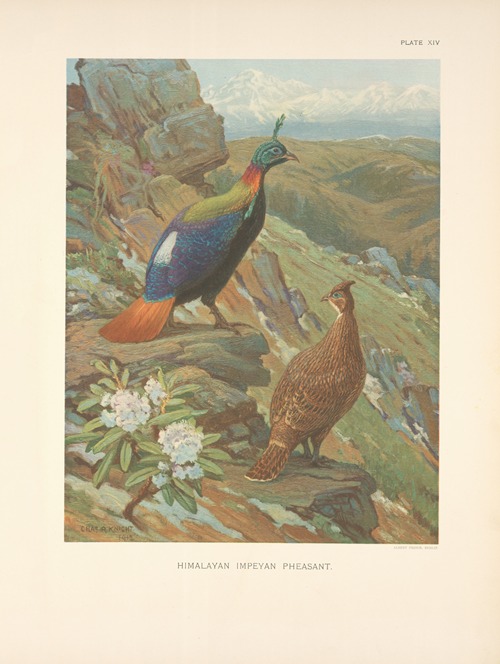

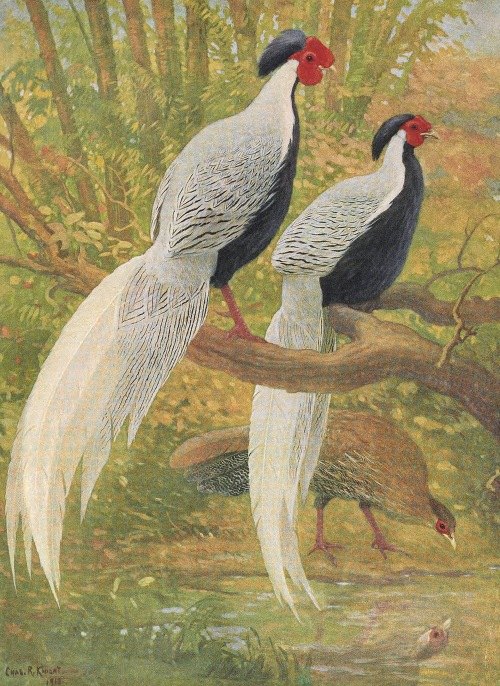

Charles Robert Knight was an American wildlife and paleoartist best known for his detailed paintings of dinosaurs and other prehistoric animals. His works have been reproduced in many books and are currently on display at several major museums in the United States.

As a child, Knight was deeply interested in nature and animals, and spent many hours copying the illustrations from his father's natural history books. Though legally blind because of astigmatism and a subsequent injury to his right eye, Knight pursued his artistic talents with the help of specially designed glasses, and at the age of twelve, he enrolled at the Metropolitan Art School to become a commercial artist. In 1890, he was hired by a church-decorating firm to design stained-glass windows, and after two years with them, became a freelance illustrator for books and magazines, specializing in nature scenes.

In his free time, Knight visited the American Museum of Natural History, attracting the attention of Dr. Jacob Wortman, who asked Knight to paint a restoration of a prehistoric pig, Elotherium, whose fossilized bones were on display. Knight applied his knowledge of modern pig anatomy, and used his imagination to fill in any gaps. Wortman was thrilled with the final result, and the museum soon commissioned Knight to produce an entire series of watercolors to grace their fossil halls. His paintings were hugely popular among visitors, and Knight continued to work with the museum until the late 1930s, painting what would become some of the world's most iconic images of dinosaurs, prehistoric mammals, and prehistoric humans.

One of Knight's best-known pieces for the American Museum of Natural History is 1897's Leaping Laelaps, which was one of the few pre-1960s images to present dinosaurs as active, fast-moving creatures (thus anticipating the "Dinosaur Renaissance" theories of modern paleontologists like Robert Bakker). Other familiar American Museum paintings include Knight's portrayals of Agathaumas, Allosaurus, Brontosaurus, Smilodon, and the Woolly Mammoth. All of these have been reproduced in numerous places and have inspired many imitations.

Knight's work for the museum was not without critics, however: many curators argued that his work was more artistic than scientific, and protested that he did not have sufficient scientific expertise to render prehistoric animals as precisely as he did. While Knight himself agreed that his murals for the Hall of the Age of Man were "primarily a work of art," he insisted that he had as much paleontological knowledge as the museum's own curators.

After Knight established a reputation at the American Museum of Natural History, other natural history museums began requesting paintings for their own fossil exhibits. In 1925, for example, Knight produced an elaborate mural for the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County which portrayed some of the birds and mammals whose remains had been found in the nearby La Brea Tar Pits. The following year, Knight began a 28-mural series for Chicago's Field Museum of Natural History, a project which chronicled the history of life on earth and took four years to complete. At the Field Museum, he produced one of his best-known pieces, a mural featuring Tyrannosaurus and Triceratops. This confrontation scene between a predator and its prey became iconic and inspired a huge number of imitations, establishing these two dinosaurs as "mortal enemies" in the public consciousness. The Field Museum's Alexander Sherman says, "It is so well-loved that it has become the standard encounter for portraying the age of dinosaurs".

Knight's work also found its way to the Carnegie Museums in Pittsburgh, the Smithsonian Institution, and Yale's Peabody Museum of Natural History, among others. Several zoos, such as the Bronx Zoo, the Lincoln Park Zoo, and the Brookfield Zoo, also approached Knight to paint murals of their living animals, and Knight enthusiastically complied. Knight was actually the only person in America allowed to paint Su Lin, a giant panda that lived at Brookfield Zoo during the 1930s.

While making murals for museums and zoos, Knight continued illustrating books and magazines, and became a frequent contributor to National Geographic. He also wrote and illustrated several books of his own, such as Before the Dawn of History (Knight, 1935), Life Through the Ages (1946), Animal Drawing: Anatomy and Action for Artists (1947), and Prehistoric Man: The Great Adventure (1949). Additionally, Knight became a popular lecturer, describing prehistoric life to audiences across the country.

Eventually, Knight began to retire from the public sphere to spend more time with his grandchildren, who shared his passion for animals and prehistoric life. In 1951, he painted his last work, a mural for the Everhart Museum in Scranton, Pennsylvania. He died in New York City, two years later.