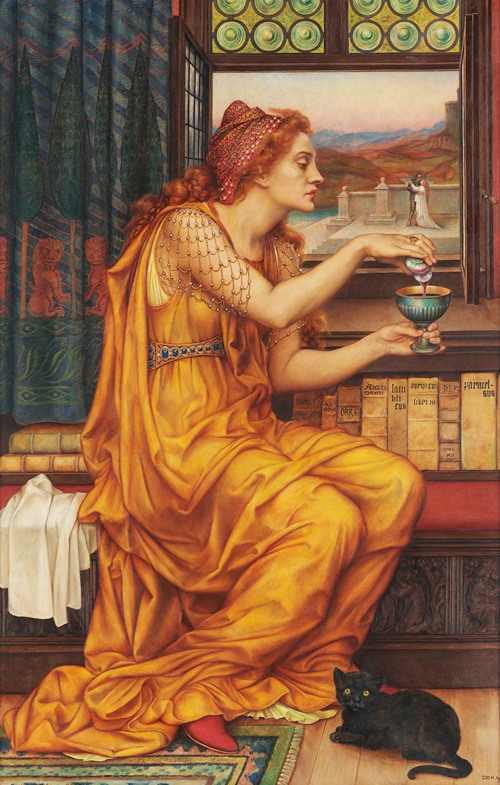

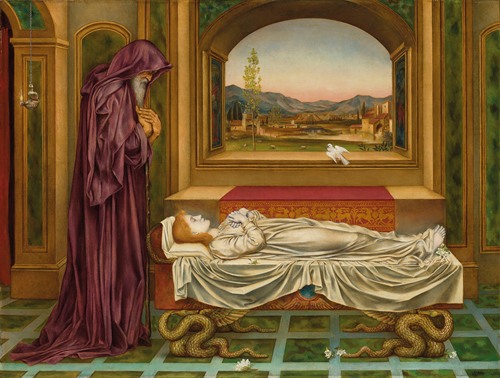

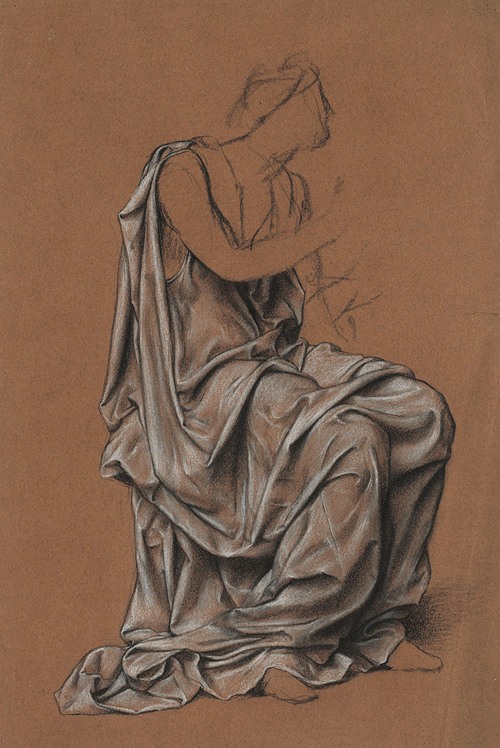

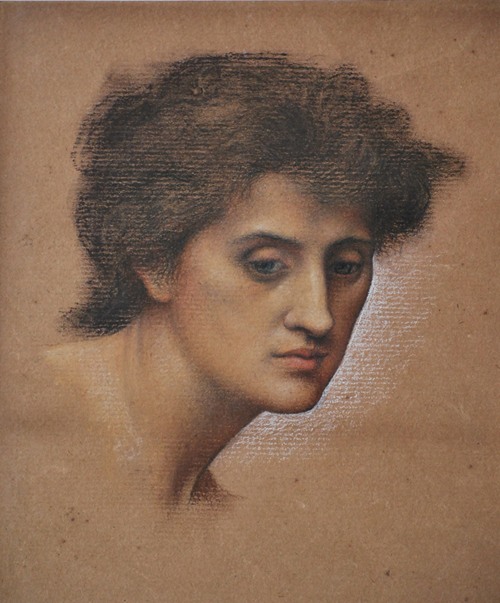

Evelyn De Morgan, née Pickering, was an English painter associated early in her career with the later phase of the Pre-Raphaelite Movement. Her paintings are figural, foregrounding the female body through the use of spiritual, mythological, and allegorical themes. They rely on a range of metaphors (such as light and darkness, transformation, and bondage) to express what several scholars have identified as spiritualist and feminist content. She boycotted the Royal Academy and signed the Declaration in Favour of Women's Suffrage in 1889. Her later works also deal with the themes of war from a pacifist perspective, engaging with conflicts like the Second Boer War and World War I.

She was born Mary Evelyn Pickering at 6 Grosvenor Street, to upper middle-class parents Percival Pickering QC, the Recorder of Pontefract, and Anna Maria Wilhelmina Spencer Stanhope, the sister of the artist John Roddam Spencer Stanhope and a descendant of Coke of Norfolk who was an Earl of Leicester.

De Morgan was educated at home; according to her sister and biographer, Anna Wilhelmina Stirling, their mother insisted that "from the first Evelyn [was to] profi[t] from the same instruction as her brother." She studied Greek, Latin, French, German, and Italian, as well as classical literature and mythology, and was also exposed at a young age to history books and scientific texts.

In August 1883, Evelyn met the ceramicist William De Morgan (the son of the mathematician Augustus De Morgan), and on 5 March 1887, they married. They spent their lives together in London, visiting Florence for half the year every year from 1895 until the outbreak of WWI in 1914. Evelyn De Morgan supported the suffrage movement, and she appears as a signatory on the Declaration in Favour of Women's Suffrage of 1889. She was also a pacifist, and expressed her horror at the First World War and Boer War in over fifteen war paintings including The Red Cross and S.O.S. In 1916 she held a benefit exhibition of these works at her studio in Edith Grove in support of the Red Cross and Italian Croce Rossa.

For the first half of their marriage, De Morgan used the profits from sales of her work to help financially support her husband's pottery business; she also actively contributed ideas to his ceramics designs. The De Morgans finally achieved financial security in 1906 after the publication of William's first novel, Joseph Vance.

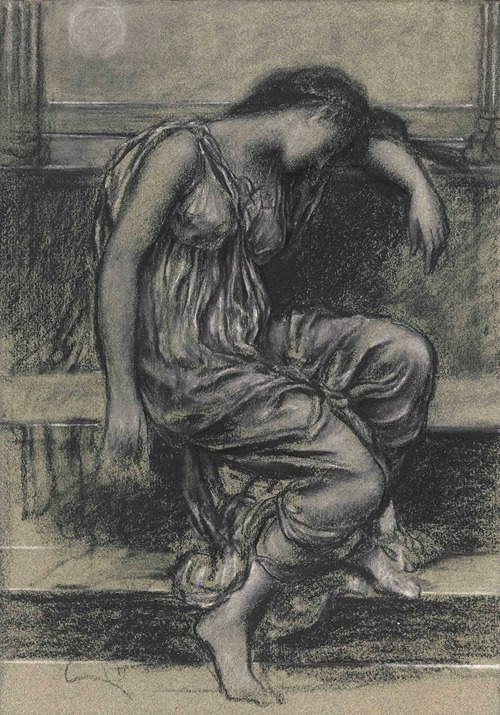

De Morgan and her husband were both spiritualists, and De Morgan’s sister and biographer A. M. W. Stirling credits them as the anonymous authors of a 1909 publication of automatic writings — communications with spirit beings — titled The Result of an Experiment. The introduction to this book describes the couple as practicing automatic writing together every night for many years of their marriage. Since precious little primary material in Evelyn De Morgan’s own hand has survived, this text provides important information on her faith and her approach to a range of issues, from her understanding of ultimate reality to her belief about the role of art in capturing spirit. From the moment that de Morgan encountered spiritualism, her perspective seemed to change, and her works started to reflect more ideas about darkness and death. De Morgan uses a range of motifs to represent spiritual ideas. A few examples are Renaissance angels, heavenly auras, a distinctive contrast between light and dark, and the symbolic use of colours. De Morgan uses complex allegories to depict her social commentary and spiritual beliefs. And the iconography in these works reflect several spiritual themes such as the progress of the spirit, the materialism of life on earth, and the imprisonment of the soul in the earthly body.

Evelyn De Morgan died on 2 May 1919 in London, two years after the death of her husband, and was buried in Brookwood Cemetery, near Woking, Surrey. Their tombstone bears an inscription from The Result of an Experiment: “Sorrow is only of the flesh / The life of the spirit is joy”.