Cyrus Leroy Baldridge was an artist, illustrator, author and adventurer. He was born to William Baldridge and Eliza Burgdorf Baldridge, in Alton, New York in 1889. When very young, his mother left his father and began a nomadic life as a traveling sales person, selling kitchen equipment from town to town. Devoted to this strong and independent woman, Baldridge's personality absorbed from her a spirit of quite exceptional individualism.

Baldridge's career in art began when the 10-year-old Cyrus was accepted as the youngest student at Frank Holme's Chicago School of Illustration. Holme became his second father. In his studio, Baldridge sat with students three times his age to do life drawings, and under Holme's direction went into the streets to make the detailed sketches meant to become newspaper illustrations. He learned to count and remember the number of buttons on a policeman's jacket, and the sad faces of tenement children, and then return to the studio to include them in finished illustrations. The tenet of art creation that he would ever remember from Holme was "Say it with a few bold strokes." He followed that rule and improved upon it through time spent with Japanese artists years later.

Baldridge was admitted to the University of Chicago in 1907 and graduated in 1911 and was evermore devoted to that institution. He was poor boy with no scholarship in an elite college. During his whole life lack of money never stopped him from anything, and at the University of Chicago he paid his way by drawing signs for campus events. He became a campus leader, most likely to succeed, Grand Marshal of the University and a model for students who remembered him long afterwards. According to Harry Hansen, "Men who knew him then will talk to you about him by the hour – but not necessarily about his drawings. They will tell you about his honesty, his candor, his sense of democracy, his unfailing good humor and his faith in his fellow man."

After college, life for Baldridge was both struggle and an exuberant adventure. While looking for commissions as an illustrator, he worked in a Chicago settlement house and in the stockyards. He became superb rider while training in the Illinois National Guard Cavalry and with that skill worked as a cow hand on the 6666 Ranch in Texas for a summer.

When World War I began, Baldridge traveled through occupied Belgium and France as a war correspondent and illustrator. Using a German letter of passage he interacted with the conquered and their conquerors. He traveled through war zones on bicycle, horse cart and horseback until his money ran out and he returned to Chicago.

Called to Mexico as a member of the National Guard he was on the Mexican/American border in 1916 to repulse Pancho Villa and in 1917 he joined the French Army as a stretcher bearer. The entrance of the United States into the war required his transfer to the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF). In the AEF he joined the talented team that brought the Stars and Stripes newspaper into being. Baldridge was the chief artist on staff that included Harold Ross, founder of The New Yorker, Alexander Woollcott, drama critic for the New York Times, and others who later achieved considerable fame. As a journalist, Baldridge traveled freely and saw as much as any general. His work appeared in virtually every issue of Stars and Stripes from March 1918 until the end of the War in November, 1918, and portrayed the full range of emotion of soldiers facing death at the Front. HaroldRoss called him the greatest illustrator of the War.

Cyrus Baldridge saw as much of the War as anyone could, having traveled with the German army as a journalist in the beginning, and later being part of both the French and American campaigns. He had walked among piles of dead soldiers and lines of innocent people filling the roads after their homes had been destroyed. He had begun as an idealistic follower of the Wilsonian dream but, by the end, was dreadfully disillusioned with war and the colonialism that lay behind it. In the Chicago Evening Post he described what he had seen as ". . . a nightmare of horror: a red vision of machine guns and dead men, inspiring only a feeling of disgust for the cold efficiency with which it was accomplished."

Baldridge's reputation as an illustrator was launched in the United States when his battlefield drawings appeared on many covers of Leslie's Weekly and Scribners. His illustrations in Stars and Stripes reached an audience of 530,000 soldiers weekly by the end of the War and many copies were sent home to family and friends. After the war he assembled his sketches as his first book, I was There with the Yanks in France. I Was There is a collection of sketches that record, better than cameras could, intimate moments of sadness, heroism and relaxation. The book's publication was more than an artistic triumph. Through it Baldridge meant to carry his perceptions of the War to the world. As he told Harry Hansen, "If only I can make the public see what war is – what a dirty, low thing it is, and how brutal it makes men, fine clean men – then they'd fight to the last ditch for the League of Nations."

Like most liberals in the 1920s Baldridge believed that war could be outlawed and espoused a one-world internationalism. He was a follower of Norman Thomas and at least once spoke on behalf of Jane Addams' pacifist Women's International League for Peace and Freedom. In 1922 he joined the Willard Straight Postof the American Legion in New York. Formed by John Dos Passos, Walter Lippman by other liberal intellectuals, it was the only Post to stand against the conservative leadership of the American Legion. In 1936, as president of the Willard Straight Post and chairman of the Legion's New York Committee on Americanism, Baldridge wrote and illustrated a 16-page booklet, Americanism -- What Is It, which was designed to be distributed in schools for use in the civics curriculum. Mild in tone and taking its ideas from the words of Lincoln, Washington, Jefferson and the Constitution, the booklet became the target of an attack by the American Legion leadership. Liberal thinkers like John Dewey and University of Chicago president Robert Maynard Hutchins gave Baldridge their support, but conservatives and, particularly, the Hearst newspapers loudly denounced it. The fight became national and even reached the floor of Congress where each side had its defenders. In the end, the booklet lost the support of the American Legion, but, selling in the thousands, it generated enormous discussion of important issues—starting with freedom of speech. Later Baldridge took more pride in writing and defending the little publication than anything else he had ever done and printed it in its entirety in his autobiography.

In 1920, Baldridge joined his life with that of the writer Caroline Singer. They built a house in Harmon, New York, but frequently turned the key in the front door and left on long journeys around the world. Caroline Singer shared Baldridge's politics, becoming a leader in the Women's International League for Peace and Freedom. She shared his work life, her writing was often enhanced with his illustrations. But most of all she shared a need, at times an almost compulsive, to know the world through other eyes. They became wanderers who left New York time after time on adventures of discovery with hardly enough money to reach the tramp steamer that would begin their journey.

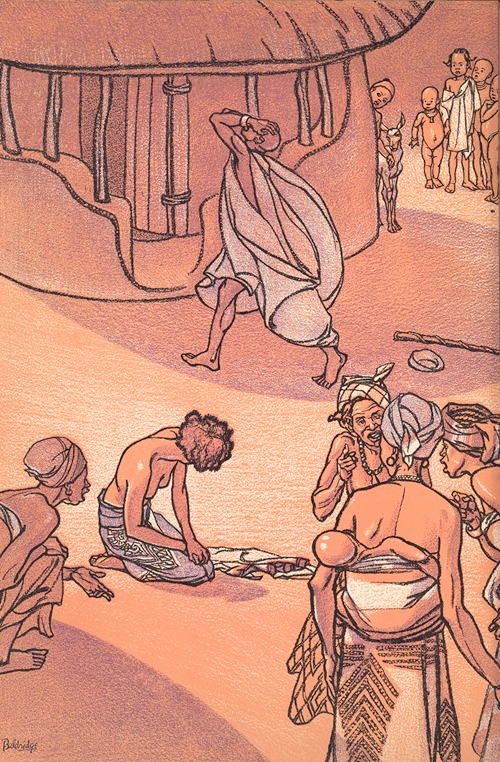

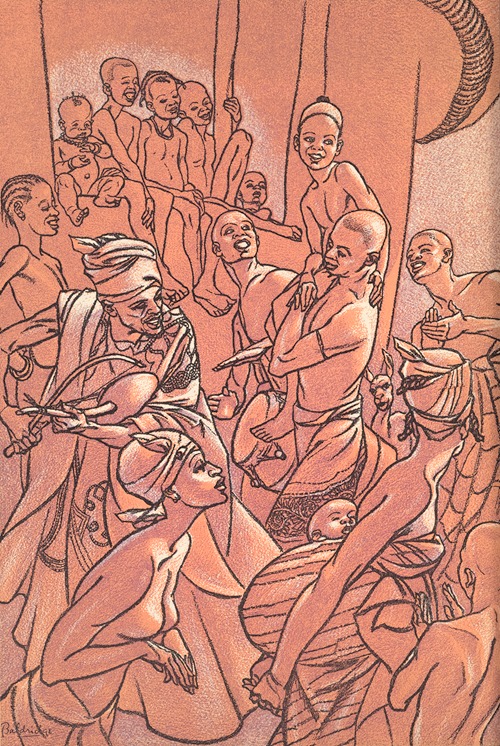

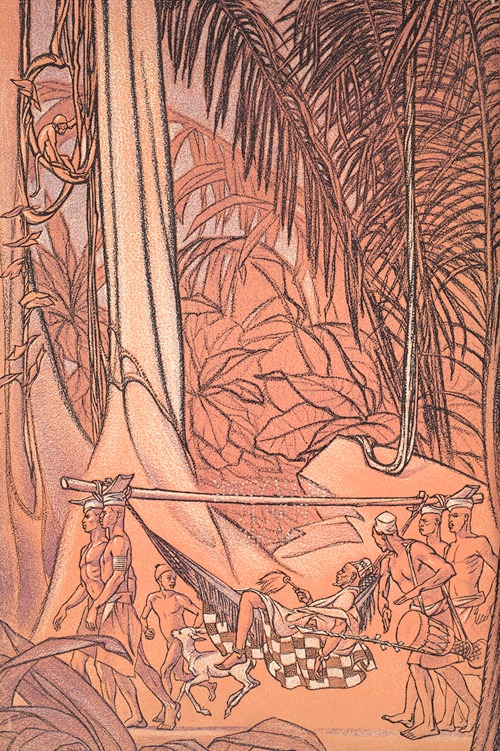

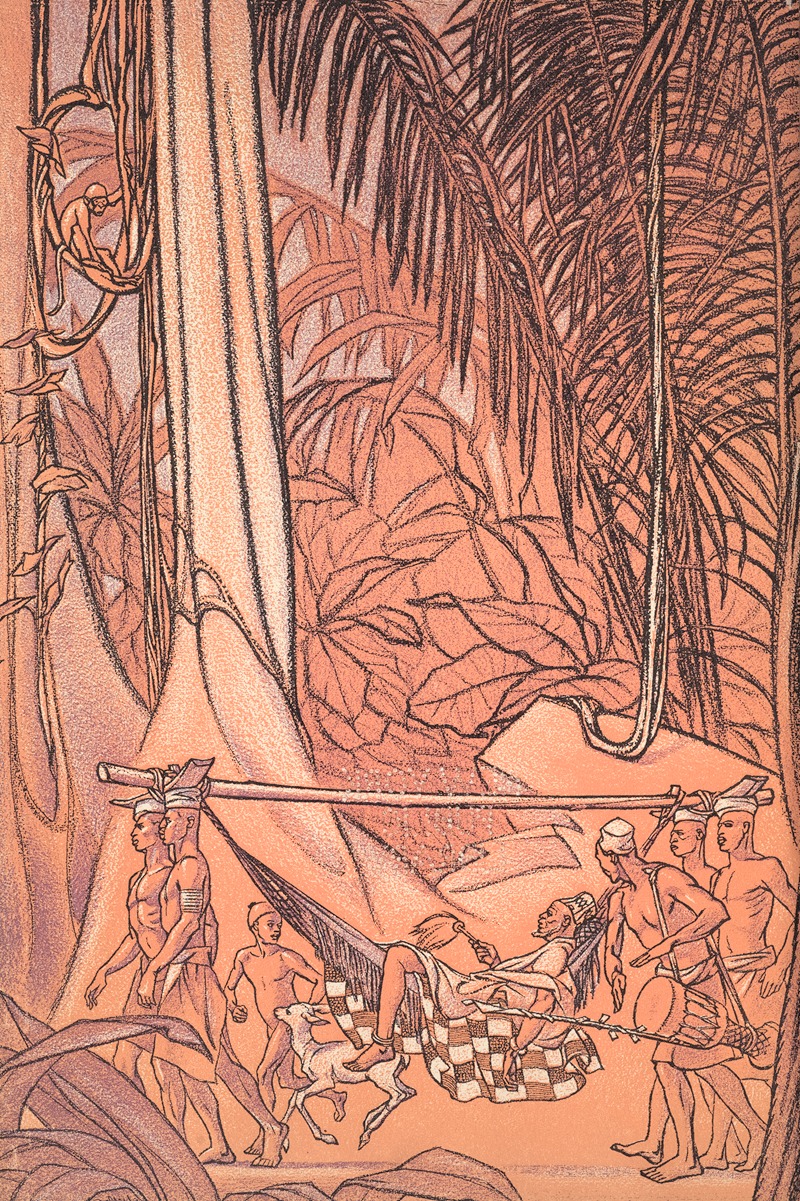

Their travel was not tourism but was designed to help comprehend the great questions of the world. To understand better the background of the Negro in America, they moved, mostly on foot, across Africa from Sierra Leone to Ethiopia. Along the way they lived in native villages where Baldridge sketched and communicated with the Africans through pictures. They traveled light, he in a golf cap and she in anything comfortable. No pith helmets, no guns, never asking or accepting the special treatment demanded by other members of their race. In India, they never saw the Taj Mahal, but they met Rabindranath Tagore and participated in dark-of-night meetings with Gandhian nationalists.

From this African journey came a marvelous book, written by Caroline Singer and lavishly illustrated by Baldridge, White Africans and Black. It is an elegant and respectful portrayal of black African culture written at a time when whites hardly even acknowledged its existence. The experience left them deeply committed to the rights of black Americans. Baldridge frequently worked for Opportunity, a journal of the Urban League, and he beautifully illustrated several books by African American authors. After his African adventure he convinced Samuel Insull to donate hundreds of his splendid sketches to Fisk University. Upon their acquisition, Charles S. Johnson, a prominent sociologist who was later to become president of Fisk, said, "The Baldridge Collection represents the best representation available of African Life." Having seen the world and its people at close hand, Baldridge was intense in his refusal to work with any author who portrayed another race as inferior or foolish.

More journeys followed to Asia and the Middle East, with other fine books growing out of them. Long periods spent in China and Japan brought him in contact with leading Asian artists. In 1921 he published A Chinese album, monotypes by Cyrus Leroy Baldridge in the journal Asia and later Baldridge and Singer together wrote A Turn to the East.

The Baldridge style was considerably changed by his exposure to the spare lines of Asian, especially Japanese, art. For a short time in the 1920s he worked with Watanabe Shozaburo in Tokyo and the 1930s he used what he had learned to producing a number of fine woodblock prints, etchings and drypoints. This work in pure art, as contrasted with his work as an illustrator, was widely admired and in 1935 he given the annual award of the Prairie Printmakers of Chicago and at about the same time his etchings were exhibited in the Smithsonian.

Baldridge's long and deep experience with the cultures of Asia, Africa and the Middle East put him in line for important commissions. He illustrated many books and articles with oriental themes the foremost of which were the stunning 1937 reissue of Hajji Baba of Isfahan by James Morier and the 1941 Translations from the Chinese by Arthur Waley. Both books were early Book-of-the-Month Club special editions and their illustrations, distributed separately by the Book of the Month Club, were framed and hung on walls in thousands of homes. In the early 1930s, Baldridge and a group of New York friends organized the Williard Straight American Legion Post to combat the dominant right-wing ideology of the Legion at that time. Baldridge was elected president of the Williard Straight Post five times and he was especially proud of a small booklet he wrote and illustrated for the Legion called Americanism: What is It. Released in 1936, the booklet was a simple restatement of American values, mostly quoted from the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution. It was distributed free by the Legion to thousands of schools, until the right wing leadership got wind that Thomas Jefferson was on the rise forced its withdrawal.

In the 1940s, Cyrus Baldridge illustrated more than one hundred books and magazine articles and, in 1947, he wrote an autobiography: Time and Chance. The book is both splendidly written and lavishly illustrated. It was quite successful, being listed on the New York Times best seller list for months. Profits from Time and Chance, combined with several years of earnings from well-paid work with the Information Please Almanac, made it possible for him and Caroline to retire to Santa Fe, New Mexico in 1951. There they lived simply in a small adobe house among like-minded free-spirits.

In Santa Fe, Baldridge began to seriously work in oils. His painting ranged over every possible theme, but chiefly portrayed New Mexican landscapes. In the thirty years between his retirement and his death, he hiked virtually the whole of northern New Mexico, sketching with charcoal or water colors, and returning home to complete his work in oils. A large number of these later works are in the collection of the University of Wyoming.

The plan of the couple had been for Caroline to write while Cyrus painted during their years of "retirement", but from the time they arrived in New Mexico she suffered from a block to the great abilities that made her so successful in New York. She wrote hardly anything and completed nothing. Later it was speculated that she had begun a series of small strokes that eventually led to dementia and death.

Caroline Singer died in 1963. Cyrus Baldridge remained incredibly active and vigorous, full of stories and opinions, until decline began in the mid-1970s. In 1977, he felt himself losing the battle against age. On the afternoon of June 6, 1977, he ended his own life with a pistol he had been issued in World War I. The bulk of his estate was left to the University of Chicago where a fine collection of his pre-1952 work can be found in its Smart Museum of Art.