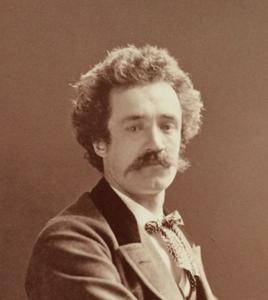

Marie-François Firmin-Girard was born on 29 May 1838 in the village of Poncin, a hamlet in the Ain region of France adjacent to the Swiss border. The landscape is comprised of a surprising variety of terrains from flat marshlands to rich agricultural plains to the Jura mountains. By age sixteen, the ambitious young artist had left his hometown to study at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris. Initially he sought out the guidance of Charles Gleyre, the Swiss painter, who offered a traditional visual arts curriculum in an independent studio setting. Later, Firmin-Girard would study with Jean-Léon Gérôme, the academic master of orientalism and anecdotal history paintings.

The late 1850s were exciting years to be an art student in Paris; the Second Empire had established a modicum of political stability, and the arts community was full of conversation about new ideas. The Barbizon painters had at last been recognized for their pioneering efforts in landscape, and a younger generation of Realists had begun to emerge as painters of daily life in France.

In 1859 as he neared the completion of his academic study, Firmin-Girard debuted at the Salon with an impressive religious image of St. Sebastian. Two years later, he won a second place award in the influential Prix de Rome competition, and enough financial support to set up his own studio on the boulevard de Clichy in Montmartre.

Both popular and critical success soon followed, although his third class medal for Après le bal at the 1863 Salon des Artistes Français was largely overshadowed by the controversy surrounding the Salon des refusés, where Edouard Manet’s Olympia was generating heated conversations. Manet’s challenge to the academic art world resonated deeply with many young artists like Firmin-Girard. Although not necessarily endorsing Manet’s formal innovations in painting, he was certainly intrigued by the depiction of contemporary life—a startling departure from the academic conventions of the time.

Western aesthetic traditions were even more profoundly transformed by contact with the utterly unfamiliar design techniques evident in Japanese woodblock prints. According to art historical tradition, Félix Bracquemond first saw Hokusai Manga in 1856 as part of the wrapping for a porcelain consignment. More reliably, a Japanese import shop called La Porte Chinoise is documented as having opened on the fashionable rue de Rivoli in 1862. In short, Japanese art was gradually finding its way to Paris; following the 1868 Meiji restoration, the trade in Japanese goods would expand exponentially. Firmin-Girard, like so many of his contemporaries, would enjoy Japanese art as an unending source of both motifs and inspiration.

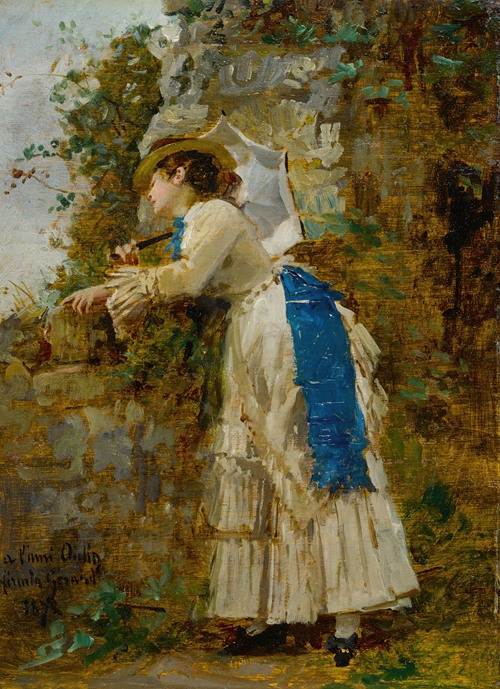

In the midst of this refreshing jolt of artistic thinking from Japan, France plunged into a destructive and ultimately devastating war with Prussia in 1870. When the hostilities officially ceased in 1871, Paris was a city divided by fierce political ideologies, and France was subjected to the humiliating occupation of enemy troops. It was in this environment that Firmin-Girard sought to re-establish his career. At the Salon of 1873, he exhibited one of his best-known paintings, La Toilette Japonaise, a slightly risqué scene of three geishas assisting each other in preparing for work. Several features are especially notable about this image: first is the oblique angle of perspective—a common technique in Japanese prints, but comparatively rare in western art in 1874. Second is the painstaking delineation of the interior furnishings and costumes, almost as if the artist hoped to offer his viewers a photographic image of a Japanese geisha’s life. This was characteristic of this early phase of Japonisme, a term coined by art critic Jules Claretie in 1872 to describe the craze for all things Japanese. As aesthetic understanding of Japanese design principles deepened, the stylistic elements would become increasingly integrated into western imagery.

In Firmin-Girard’s work, this integration of Japanese compositional principles can be seen in unexpected ways. For example, his cityscapes from the 1880s and 1890s appear to be fairly traditional renditions of attractive and saleable picturesque vistas—until the viewer looks carefully. Then the spatial complexities become apparent as the perspective lines are undermined by a plethora of oblique angles, and even discontinuity. At first glance, a painting such as Ile de la Cité and the Cathedral of Notre Dame seems pleasant, but unremarkable, until careful observation reveals the crossing perspective lines in middle distance. Suddenly, the scene takes on a mysterious quality, as the bridge across the Seine seems to dissipate in a haze of light. Like the Impressionists, Firmin-Girard’s appreciation of Japonisme led him to a serious investigation of composition principles, which would ultimately result in the creation of a modernist aesthetic suited to the industrialized world of the late nineteenth century.

Throughout his very long career, Firmin-Girard enjoyed considerable commercial and critical approbation. His paintings, routinely shown at the annual Salon for thirty years, received frequent and positive critical attention. In 1874, Les fiancés won a second-class medal; and at the Exposition Universelle of 1900, he was awarded a bronze medal for Le Quai aux Fleurs and Berger d'Onival.

The last decades of Firmin-Girard’s life are less well known. Although his paintings continued to sell very well in commercial galleries and auction houses, he seems to have retired to the countryside at some point in the early twentieth century. Perhaps he felt the need to escape from yet another war between France and Germany as World War I began its downward spiral into ever-increasing horror; or perhaps he simply felt it was time to return to a quieter life outside of Paris. Whatever his reasons, Firmin-Girard moved to the small town of Montluçon in the Auvergne region, and probably not coincidentally, far south of the fighting in the north. He died there at age 83 in 1921.

Janet Whitmore, Ph.D.

More Artworks by Marie-François Firmin-Girard (View all 24 Artworks)