Thomas Wright was an English astronomer, mathematician, instrument maker, architect and garden designer. He was the first to describe the shape of the Milky Way and to speculate that faint nebulæ were distant galaxies.

Wright was born at Byers Green in County Durham being the third son of John and Margaret Wright of Pegg's Poole House. His father was a carpenter. He was educated at home as he suffered from speech impediment and then at King James I Academy. In 1725 he entered into clock-making apprenticeship to Bryan Stobart of Bishop Auckland, continuing to study on his own. He also took courses on mathematics and navigation at a free school in the parish of Gateshead founded by Dr. Theophilus Pickering. Then, he went to London to study mathematical instrument-making with Heath and Sisson and made a trial sea voyage to Amsterdam.

In 1730, he set up a school in Sunderland, where he taught mathematics and navigation. He later moved back to London to work on a number of projects for his wealthy patrons. He traveled in 1746-7 to Ireland which resulted in a book, Louthiana, with plans and engravings of the ancient monuments of County Louth, published in London in 1748. That was before retiring to County Durham and building a small observatory at Westerton.

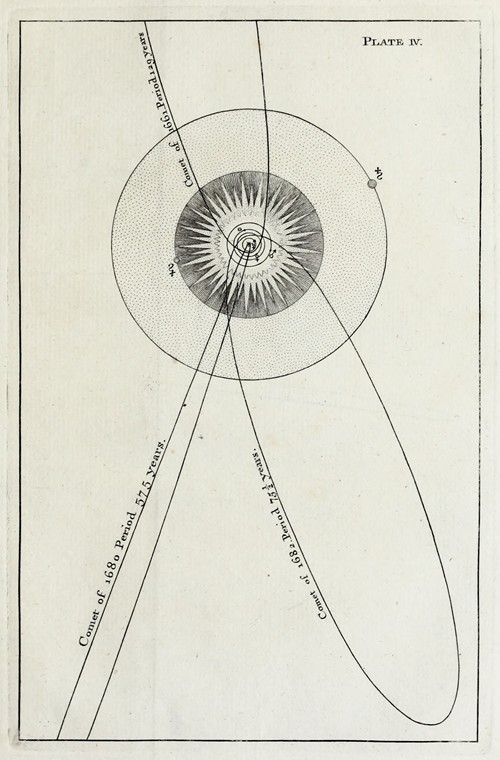

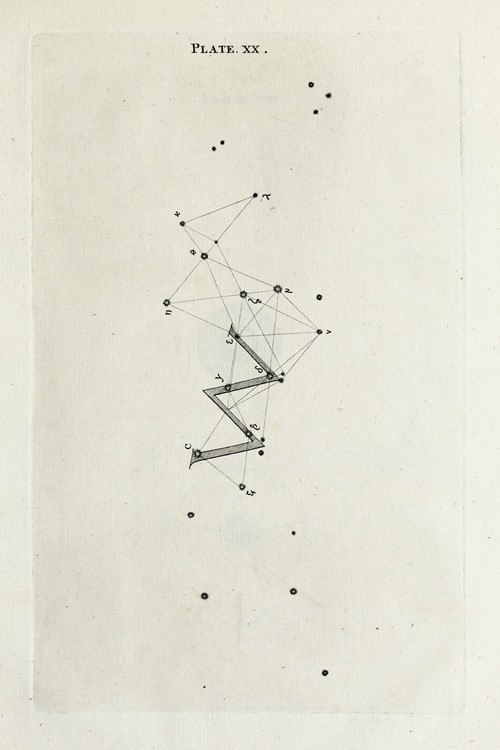

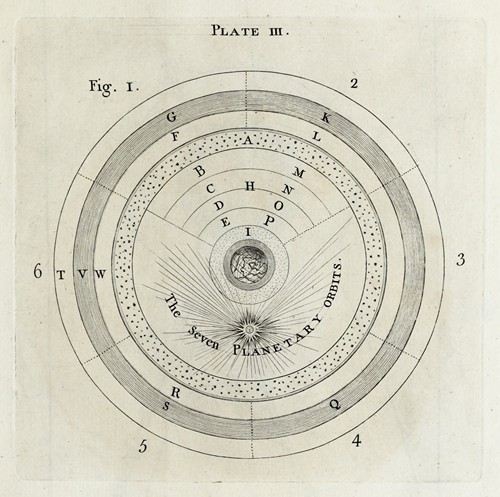

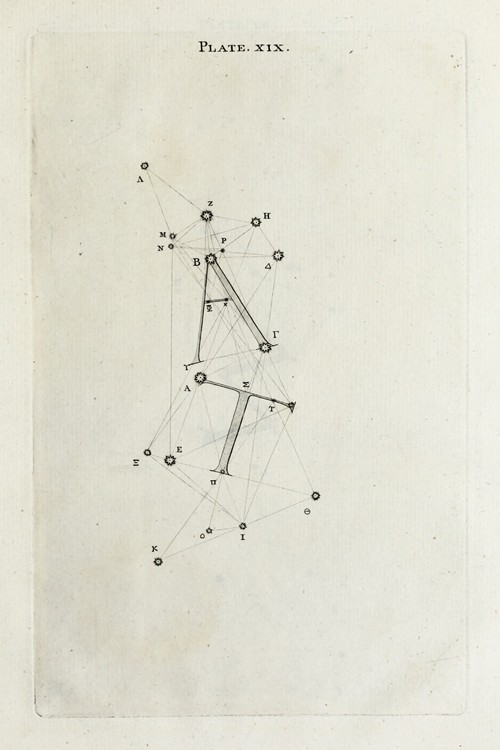

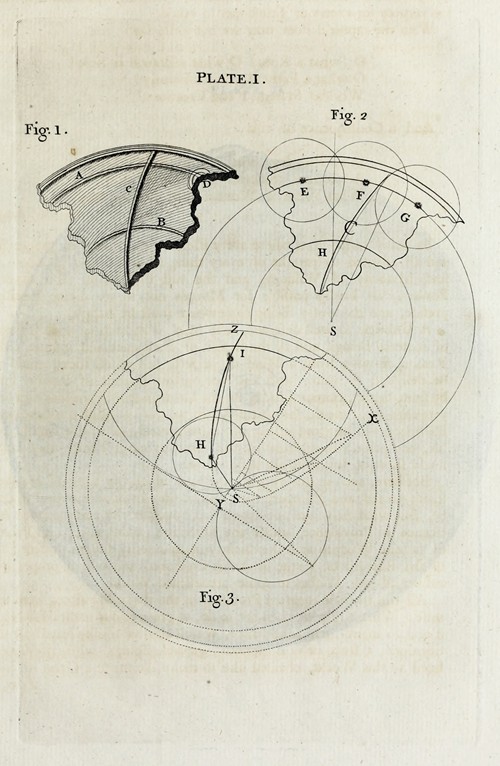

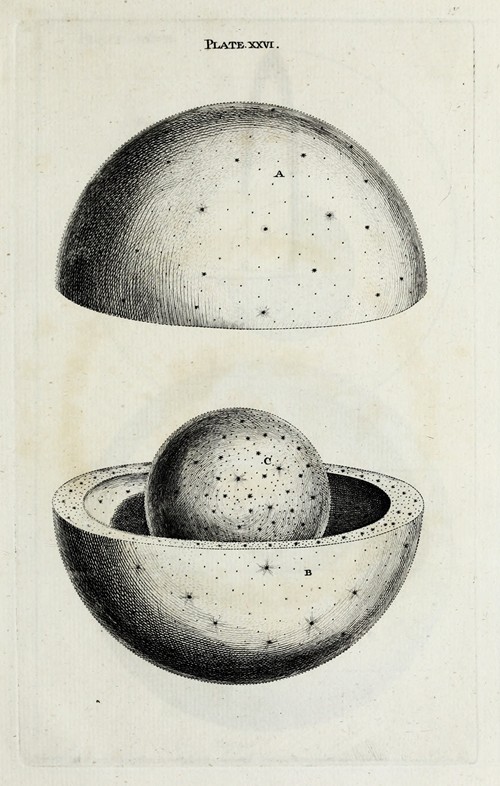

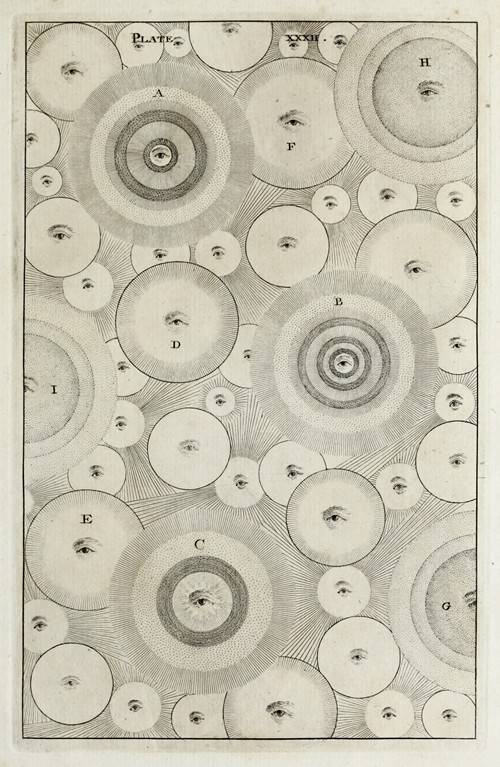

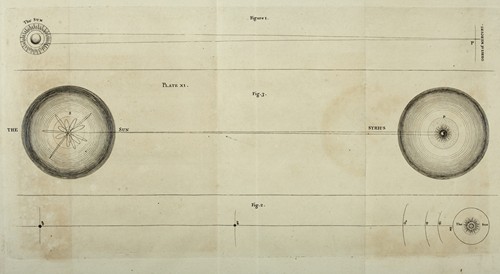

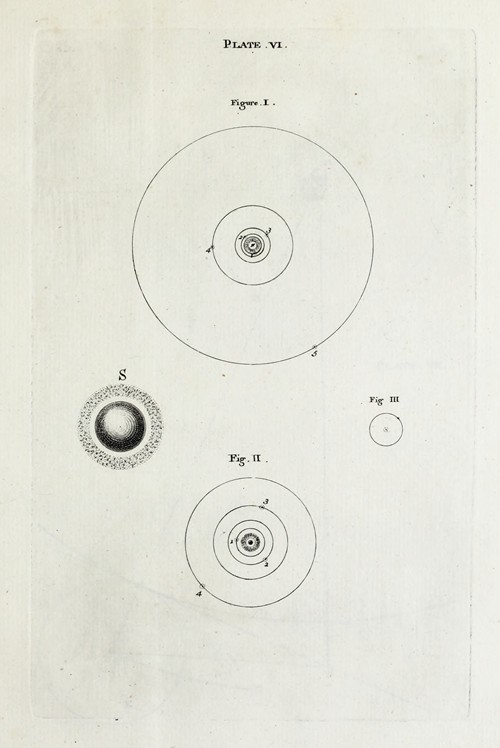

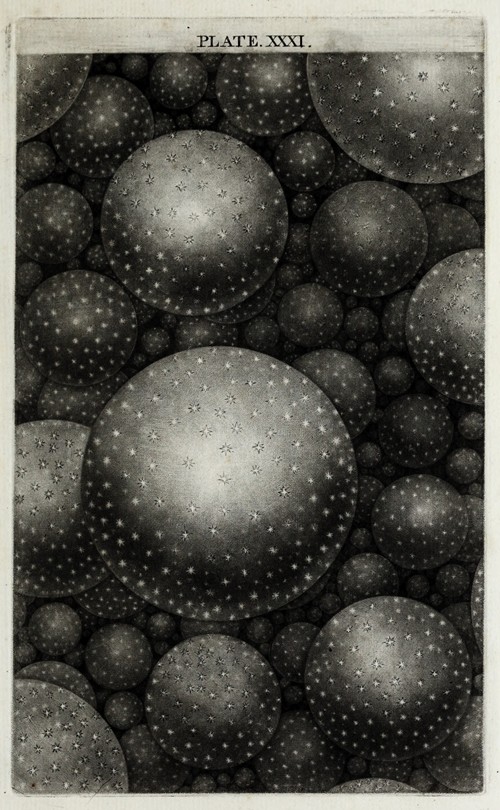

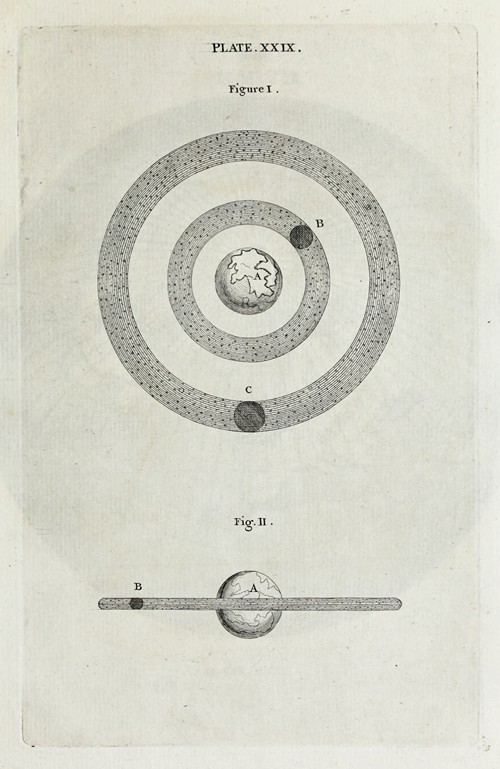

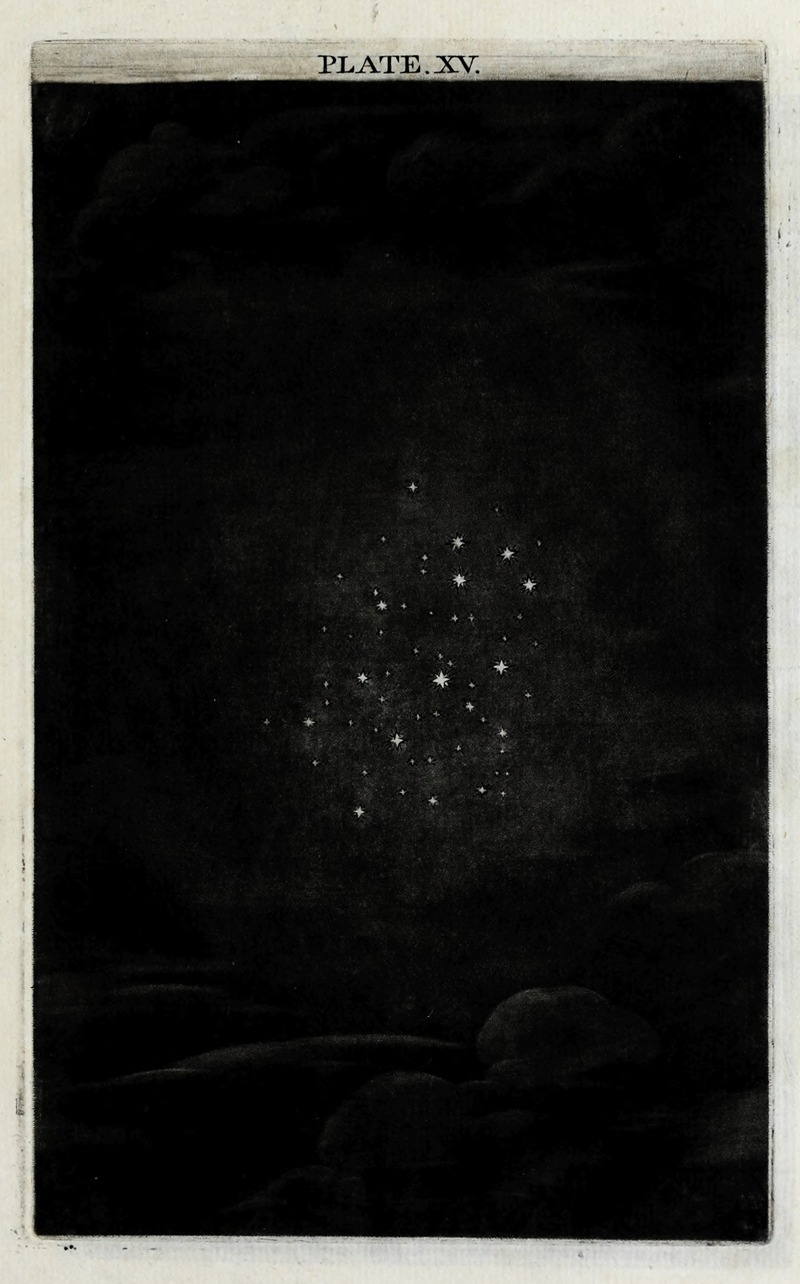

Wright's publication An original theory or new hypothesis of the Universe (1750) explained the appearance of the Milky Way as "an optical effect due to our immersion in what locally approximates to a flat layer of stars." This work influenced Immanuel Kant in writing his Universal Natural History and Theory of the Heavens (1755). The theory was later empirically advanced by William Herschel in 1785, leading to galactocentrism (a form of heliocentrism, with the Sun at the center of the Milky Way). Another of Wright's ideas, which is also often attributed to Kant, was that many faint nebulæ are actually incredibly distant galaxies. Wright wrote:

...the many cloudy spots, just perceivable by us, as far without our Starry regions, in which tho' visibly luminous spaces, no one star or particular constituent body can possibly be distinguished; those in all likelihood may be external creation, bordering upon the known one, too remote for even our telescopes to reach.

Kant termed these "island universes." However "scientific arguments were marshalled against such a possibility," and this view was rejected by almost all scientists until 1924, when Edwin Hubble showed "spiral nebulæ" were distant galaxies by measuring Cepheids.

In his letters, Wright emphasised the possible enormity of the universe, and the tranquility of eternity:

In this great Celestial Creation, the Catastrophy of a World, such as ours, or even the total Dissolution of a System of Worlds, may possibly be no more to the great Author of Nature, than the most common Accident in Life with us, and in all Probability such final and general DoomsDays may be as frequent there, as even Birth-Days or Mortality with us upon this Earth.

Such a Prothesis can scarce be called less than an ocular Revelation, not only shewing us how reasonable it is to expect a future Life, but as it were, pointing out to us the Business of an Eternity, and what we may with the greatest Confidence expect from the eternal Providence, dignifying our Natures with something analogous to the Knowledge we attribute to Angels; from whence we ought to despise all the Vicissitudes of adverse Fortune, which make so many narrow-minded Mortals miserable.

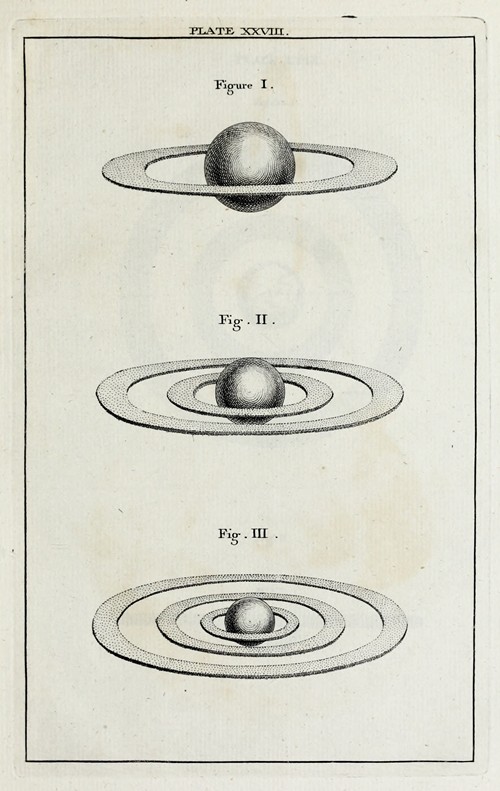

He was also credited with expanding the Grand Orrery to include Saturn. The orrery is now at the Science Museum, London.

Wright has been credited with work for William Capel, 3rd Earl of Essex at Cassiobury Park in Watford, illustrating his designs in A Walk in Cassiobury Gardens and Views of Cassiobury. In Grotesque Architecture of 1767 there is a design for a rockwork bridge to decorate "the fine piece of water" he had "with great pleasure seen... at Cassiobury", believed[by whom?] to be by Wright. A man of talents, he also gave the Earl's daughters mathematical instruction. Another patron was the Earl of Halifax, at Horton House.

In the 1750s, he laid out the grounds of Netheravon House, Wiltshire and after 1753, completed the design and construction of Horton Hall in Northamptonshire and gardens. He designed in 1769 the folly or eye-catcher known as Codger Fort at Rothley, Northumberland, on the Wallington Hall estate.

One of the largest existing examples of Wright's work is the Stoke Park Estate. The estate was remodelled by Wright between 1748 and 1766.

Wright died in 1786 in Byers Green and was buried in the churchyard of St Andrew's, South Church, Bishop Auckland. He was survived by his illegitimate daughter.