Louis Raemaekers was a Dutch painter and editorial cartoonist for the Amsterdam newspaper De Telegraaf during World War I, noted for his anti-German stance.

He was born and grew up in Roermond, Netherlands during a period of political and social unrest in the city, which at that time formed the battleground between Catholic clericalism and liberalism. Louis’ father published a weekly journal called De Volksvriend (Friend of the People) and was an influential man in liberal circles. His battle against the establishment set the tone for his son’s standpoint several decades later, when he fought against the occupation of neutral Belgium at the start of the First World War. His mother was of German descent. He was trained – and later working – as a drawing teacher and made landscapes and children's books covers and illustrations in his free time. In 1906 his life took a decisive turn when he accepted the invitation to draw political cartoons for leading Dutch newspapers, first from 1906 to 1909 for the Algemeen Handelsblad and from 1909 onwards for De Telegraaf.

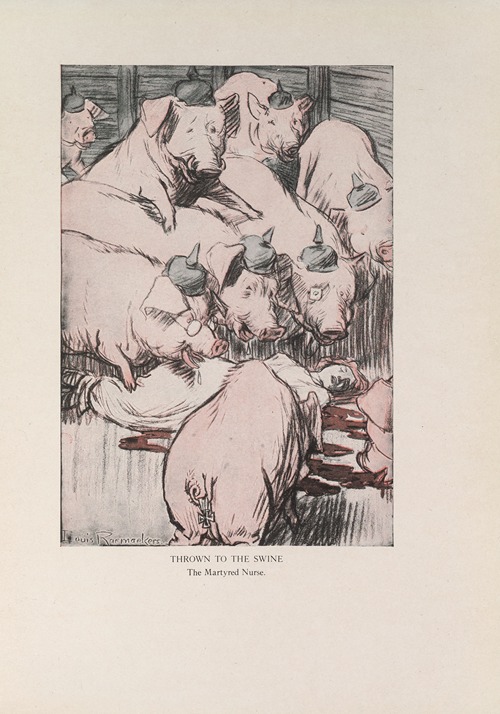

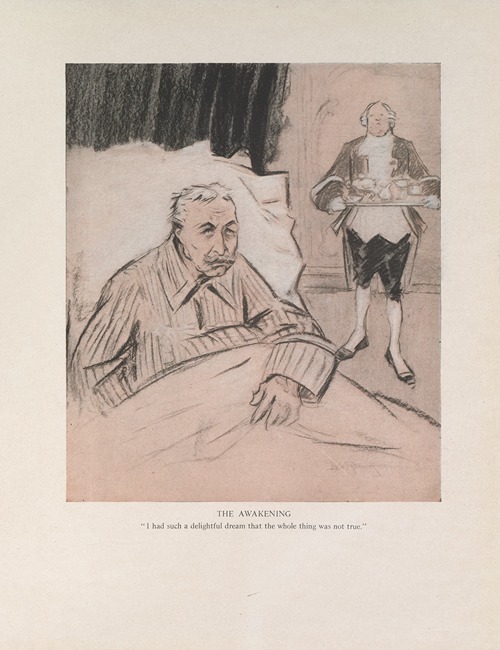

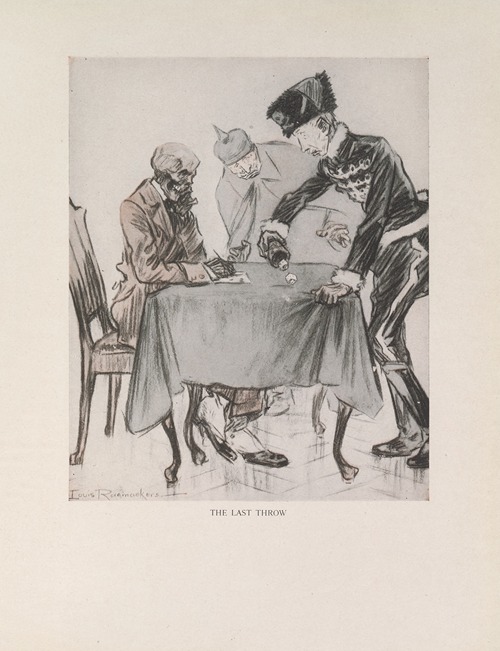

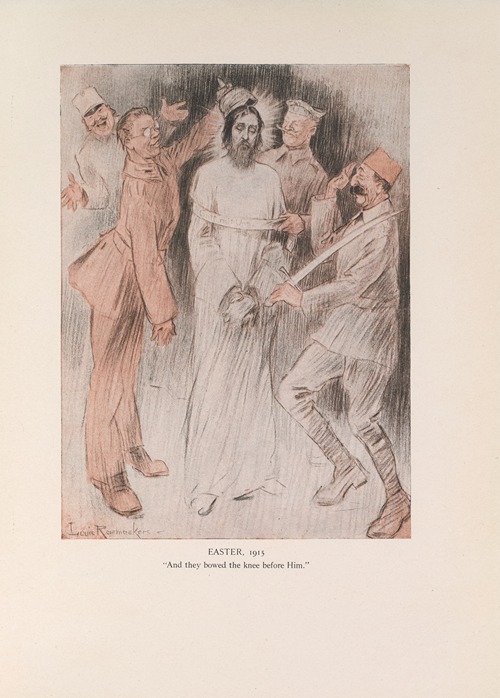

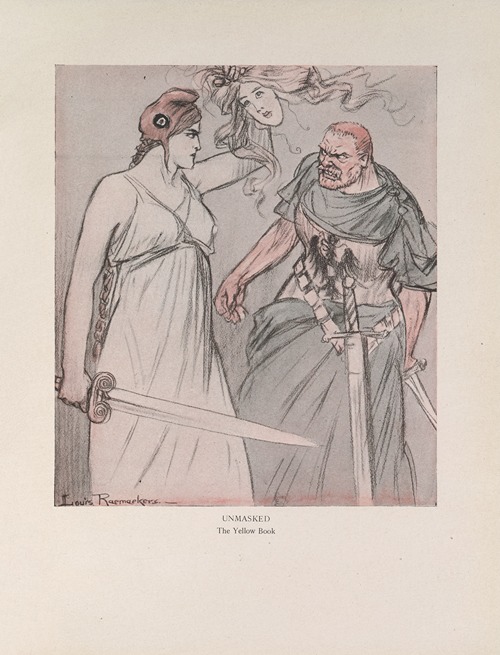

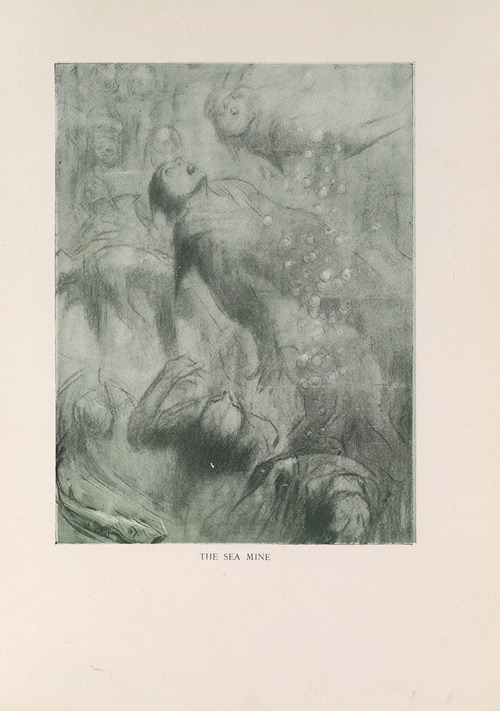

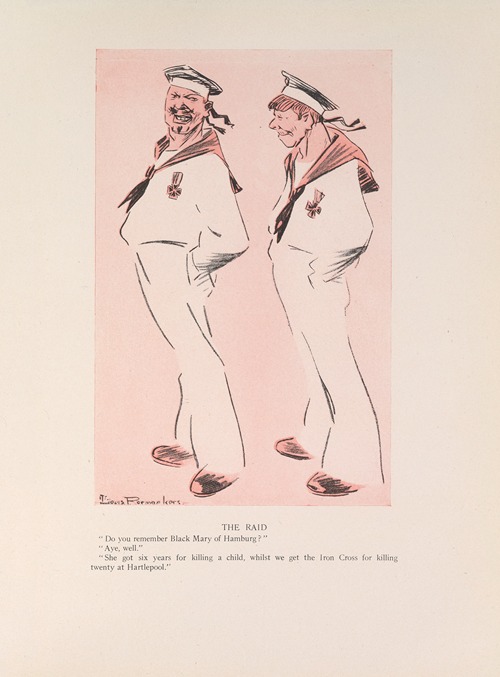

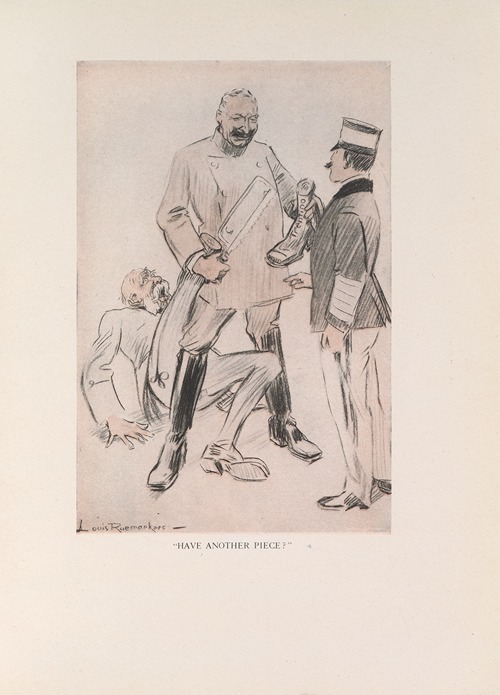

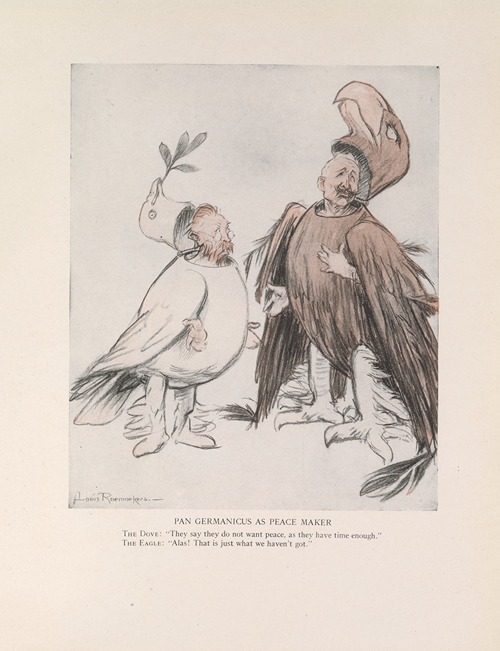

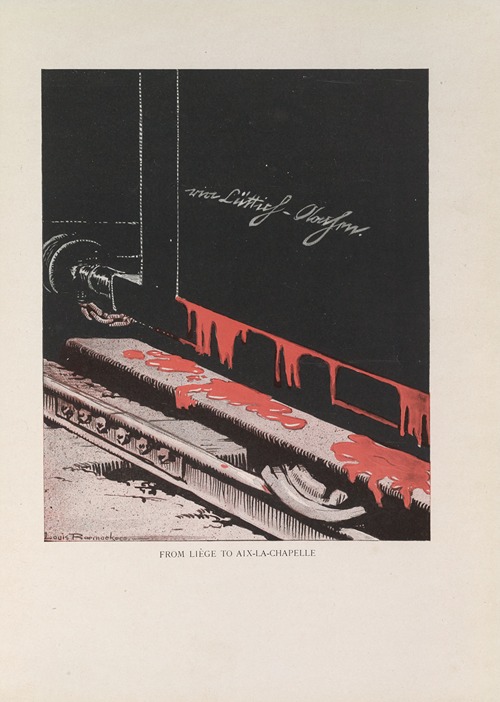

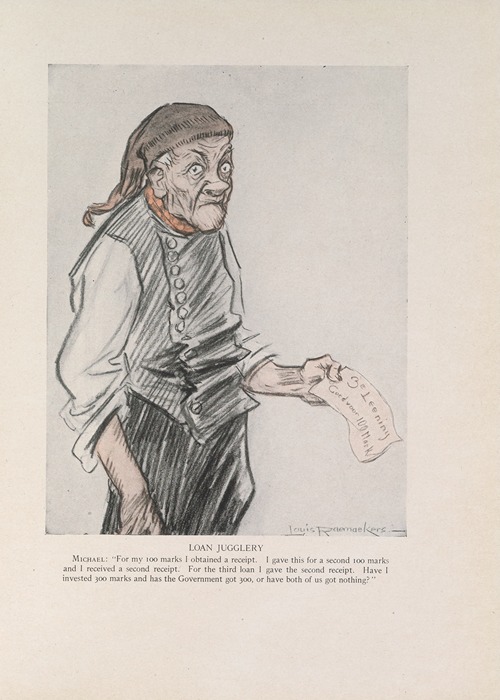

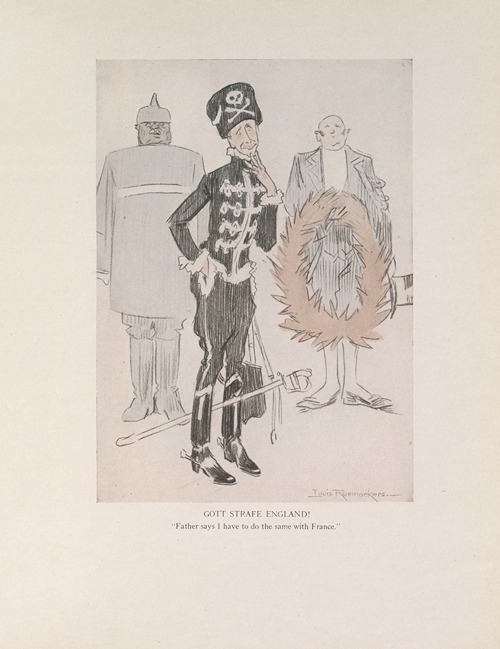

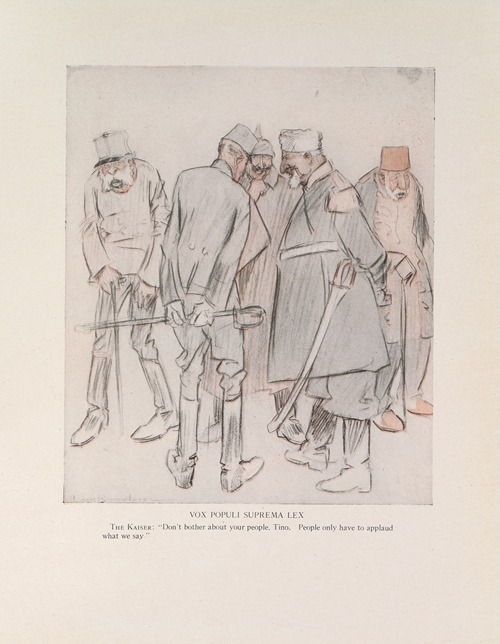

Immediately after the Germans invaded Belgium, Louis Raemaekers became one of their fiercest critics. His message was clear: the Netherlands had to take sides for the Allies and abandon its neutral stance. His graphic cartoons depicted the rule of the German military in Belgium, portrayed the Germans as barbarians and Kaiser Wilhelm II as an ally of Satan. His work was confiscated on several occasions by the Dutch government and he was criticized by many for endangering the Dutch neutrality. The minister of Foreign Affairs John Loudon invited Raemaekers, the owner of De Telegraaf H.M.C. Holdert and the editor-in-chief Kick Schröder under pressure from the German government to a meeting, at which he requested them to avoid ‘anything that tends towards insulting the German Kaiser and the German army’. It was not possible to prosecute Raemaekers for as long as the country was not under martial law. But the pressure on him continued, also from Germany: in September 1915 the rumor even started circulating that the German government had offered a reward of 12,000 guilders for Raemaekers, dead or alive, but proof of an official statement has never been found.

Louis Raemaekers achieved his greatest successes outside his native country. He left for London in November 1915, where his work was exhibited in the Fine Art Society on Bond Street. It was received with much acclaim. Raemaekers became an instant celebrity and his drawings were the talk of the town: ‘they formed the subject of pulpit addresses, and during two months, the galleries where they have been exhibited have been thronged to excess. Practically every cartoon has been purchased at considerable prices.’ He decided to settle in England and his family followed in early 1916. His leaving the Netherlands for London was a godsend for all concerned. Henceforth, the Dutch government could distance itself from the cartoonist and his work in its diplomatic relations, thus stabilising its position vis-à-vis Germany, while Raemaekers himself could cease his hopeless campaign to get the Netherlands to abandon its neutral stance. He may also have realised for himself that his aim of persuading his country to take up arms and thus avoid the fate of Belgium was not very realistic. From early 1915 Raemaekers' cartoons had already appeared in British newspapers and magazines. In early 1916 he signed a contract with the Daily Mail and they appeared in this newspaper on a regular basis for the next two years.

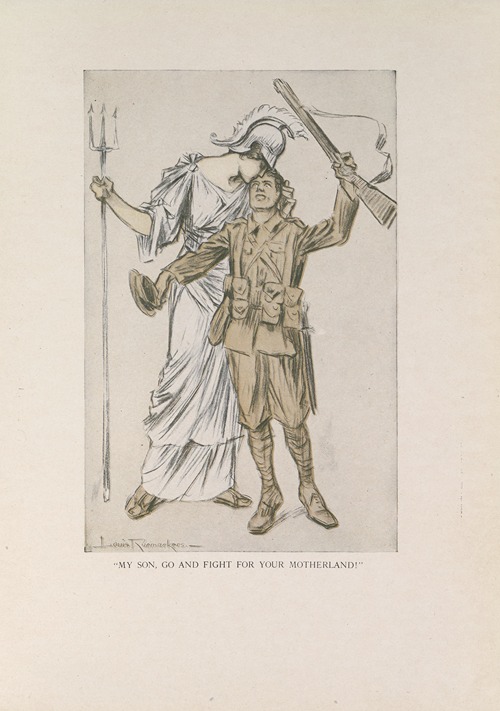

The most important aspect of Raemaekers’ career is undoubtedly his role in Allied war propaganda. Soon after his arrival in London he was contacted by Britain's War Propaganda Bureau Wellington House namely to ensure the mass distribution of his work both in England and elsewhere in support of Allied propaganda. Forty of his most captive cartoons were published in Raemaekers Cartoons, which was immediately translated in eighteen languages and distributed worldwide in neutral countries. This was the beginning of a new phase in his life, one which brought him world renown. Among the Allies and in neutral countries, it was specifically Raemaekers' alleged neutral status that gave him credibility. This was most effusively expressed by his good friend Harry Perry Robinson, a not totally unbiased journalist from The Times in Raemaekers' album The Great War: a Neutral’s Indictment (1916): ‘Raemaekers’ testimony is a testimony of an eye-witness. He saw the pitiable stream of refugees which poured from desolated Belgium across the Dutch frontier; and he heard the tale of the abominations which they had suffered from their own lips. ... His message to the world, therefore, when he began to speak, had all the authority not only of a Neutral who was unbiased, but of a Neutral who knew.’

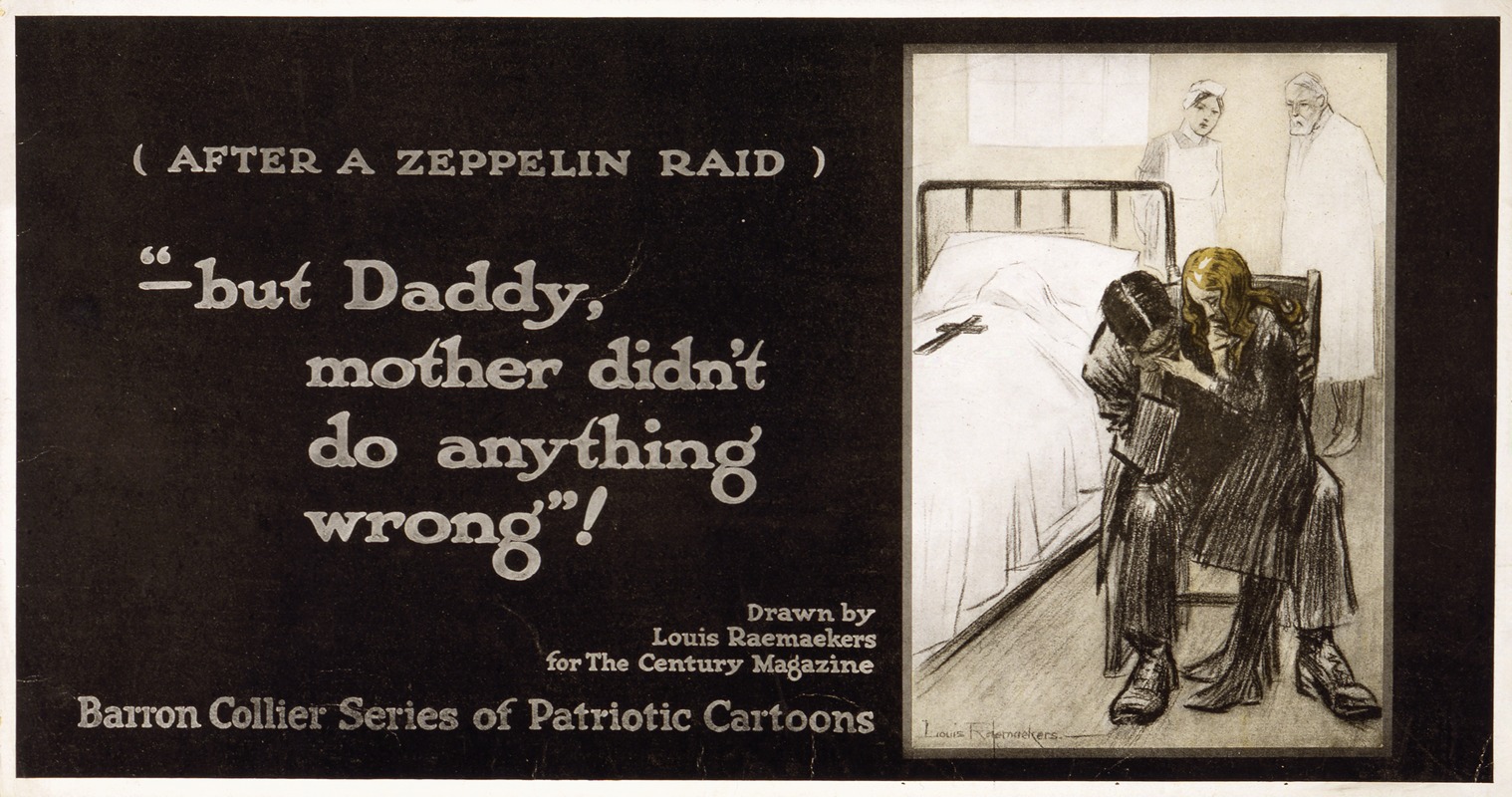

After the first exhibition in London, many others followed suit, first in the United Kingdom and France, soon afterwards in many countries over the world. Albums, pamphlets, posters, postcards and cigarette cards bearing reproductions of his work soon became also available. His drawings were even recreated as tableaux vivants. The total number of Raemaekers' cartoons distributed in this major propaganda effort increased quickly into the millions.

From the summer of 1916 onwards efforts were made to distribute Raemaekers' work in the most powerful of the neutral countries, the United States. At the request of Wellington House Raemaekers visited the USA in 1917 to draw attention to his work. The United States had declared war on Germany shortly before, and the Allies hoped that his presence would sway public opinion to their cause. His tour was a triumph. Raemaekers gave lectures and interviews, drew caricatures for the movie cameras, was a popular guest at society functions, and met President Woodrow Wilson and former President Theodore Roosevelt. Soon after his arrival he signed – to everyone's surprise – a contract with the International News Service, the syndicate of William Randolph Hearst. The Hearst newspapers were viewed as pro-German and had been cut off from all Allied news sources. But Raemaekers' own theory: "this is the most important target group because the readers are poisoned daily by tendentious articles" proved successful. Statistics show that by October 1917, more than two thousand American newspapers had published Raemaekers’ cartoons in hundreds of millions of copies. The popularisation of his work is regarded as the largest propaganda effort of the First World War.

Following the end of the First World War, Louis Raemaekers settled in Brussels. He was an advocate of the League of Nations and devoted many sketches and articles to the cause of unity in Europe. Meanwhile, he kept a close and suspicious eye on events in Germany. Interest in his work waned in Britain and France, where his war cartoons were still fresh in the public’s memory. People had had enough of his depictions of atrocities. A Dutch publisher rejected a collection of his illustrations because ‘the public is rather weary of war topics’. In 1927 he created a comic book about TBC named Gezondheid Is De Grootste Schat. In the thirties, however, people began to think that Raemaekers might be right about Germany. He grew more productive, but the artistic and content-related quality of his work suffered proportionately. He remained loyal to De Telegraaf until well into the thirties, even after the paper’s management became pro-German. He took the same stance as during the First World War towards the Hearst Press: these readers were his most important target group.

Raemaekers fled to the United States shortly before the start of the Second World War and remained there until 1946, when he returned to Brussels. He had not been forgotten in the Netherlands, but it was only on his eightieth birthday, in 1949, that his native country gave him the recognition that he had long desired: he was made an honorary citizen of the City of Roermond. After an absence of almost forty years, Raemaekers returned to the Netherlands in 1953.

He died in Scheveningen near The Hague in 1956.