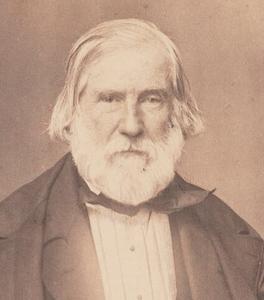

Francis Danby was an Irish painter of the Romantic era. His imaginative, dramatic landscapes were comparable to those of John Martin. Danby initially developed his imaginative style while he was the central figure in a group of artists who have come to be known as the Bristol School. His period of greatest success was in London in the 1820s.

Born in the south-east of Ireland, he was one of a set of twins; his father, James Danby, farmed a small property he owned near Wexford, but his death, in 1807, caused the family to move to Dublin, while Francis was still a schoolboy. He began to practice drawing at the Royal Dublin Society's schools; and under an erratic young artist named James Arthur O'Connor he began painting landscapes. Danby also made acquaintance with George Petrie.

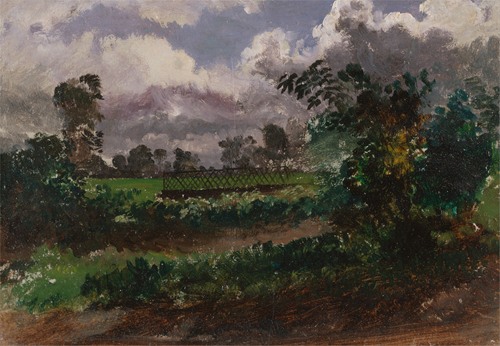

In 1813 Danby left for London together with O'Connor and Petrie. This expedition, undertaken with very inadequate funds, quickly came to an end, and they had to get home again by walking. At Bristol they made a pause, and Danby, finding he could get trifling sums for watercolours, remained there working diligently and sending to the London exhibitions pictures of importance. There his large oil paintings quickly attracted attention.

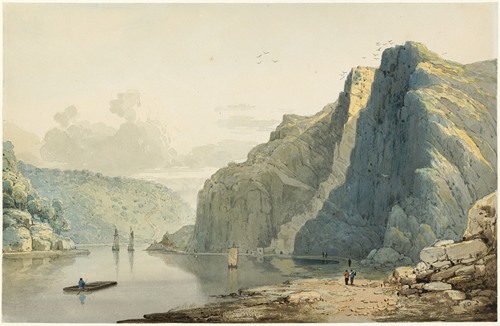

From around 1818/19, Danby was a member of the informal group of artists which has become known as the Bristol School, taking part in their evening sketching meetings and sketching excursions visiting local scenery. His View of the Avon Gorge (1822) depicts figures sketching in a location favoured by the group. He remained connected with members of the Bristol School for around a decade, even after leaving Bristol in 1824.

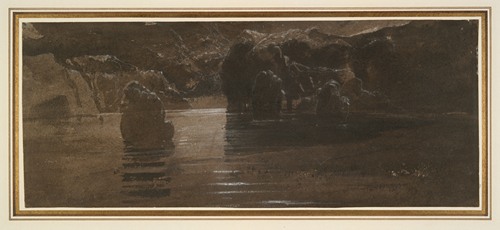

The Upas Tree (1820) and The Delivery of Israel (1825) brought him his election as an Associate Member of the Royal Academy. He left Bristol for London, and in 1828 exhibited his Opening of the Sixth Seal at the British Institution, receiving from that body a prize of 200 guineas; and this picture was followed by two others on the theme of the Apocalypse.

Danby painted "vast illusionist canvases" comparable to those of John Martin – of "grand, gloomy and fantastic subjects which chimed exactly with the Byronic taste of the 1820s."