Robert Seymour was a British illustrator known for his illustrations for The Pickwick Papers by Charles Dickens and for his caricatures. He committed suicide after arguing with Dickens over the illustrations for Pickwick.

Seymour was born in Somerset, England in 1798, the second son of Henry Seymour and Elizabeth Bishop. Soon after moving to London Henry Seymour died, leaving his wife, two sons and daughter impoverished. In 1827 his mother died, and Seymour married his cousin Jane Holmes, having two children, Robert and Jane.

After his father died, Robert Seymour was apprenticed as a pattern-drawer to a Mr. Vaughan of Duke Street, Smithfield, London. Influenced by painter Joseph Severn RA, during frequent visits to his uncle Thomas Holmes of Hoxton, Robert's ambition to be a professional painter was achieved at the age of 24 when, in 1822, his painting of a scene from Torquato Tasso's Jerusalem Delivered, with over 100 figures, was exhibited at the Royal Academy.

He was commissioned to illustrate the works of Shakespeare; Milton; Cervantes, and Wordsworth. He also produced innumerable portraits, miniatures, landscapes, etc., as can be seen in two Sketchbooks; Windsor; Eaton; Figure Studies; Portraits at the Victoria and Albert Museum. After the rejection of his second Royal Academy submission, he continued to paint in oils, mastered techniques of copper engraving, and began illustrating books for a living.

From 1822–27, Seymour produced designs for a wide range of subjects including: poetry; melodramas; children's stories; and topographical and scientific works. A steady supply of such work enabled him to live comfortably and enjoy his library and fishing and shooting expeditions with his friends: Lacey the publisher, and the illustrator George Cruikshank. In 1827, the year of his mother's death and his marriage, Robert Seymour's publishers, Knight and Lacey, were made bankrupt, owing Seymour a considerable amount of money.

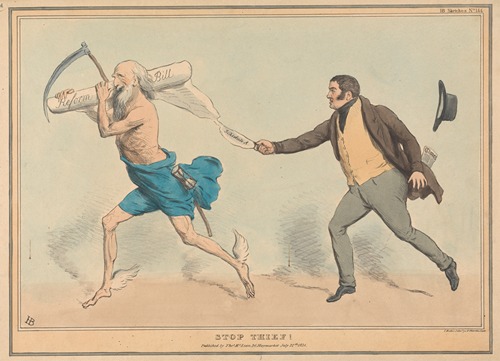

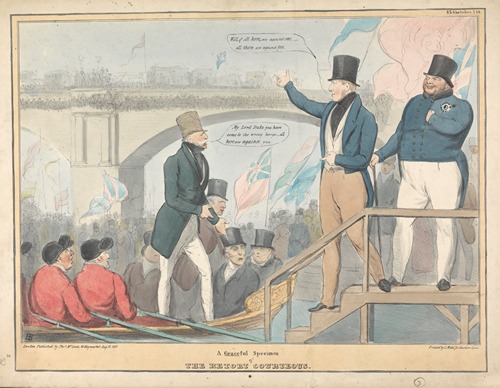

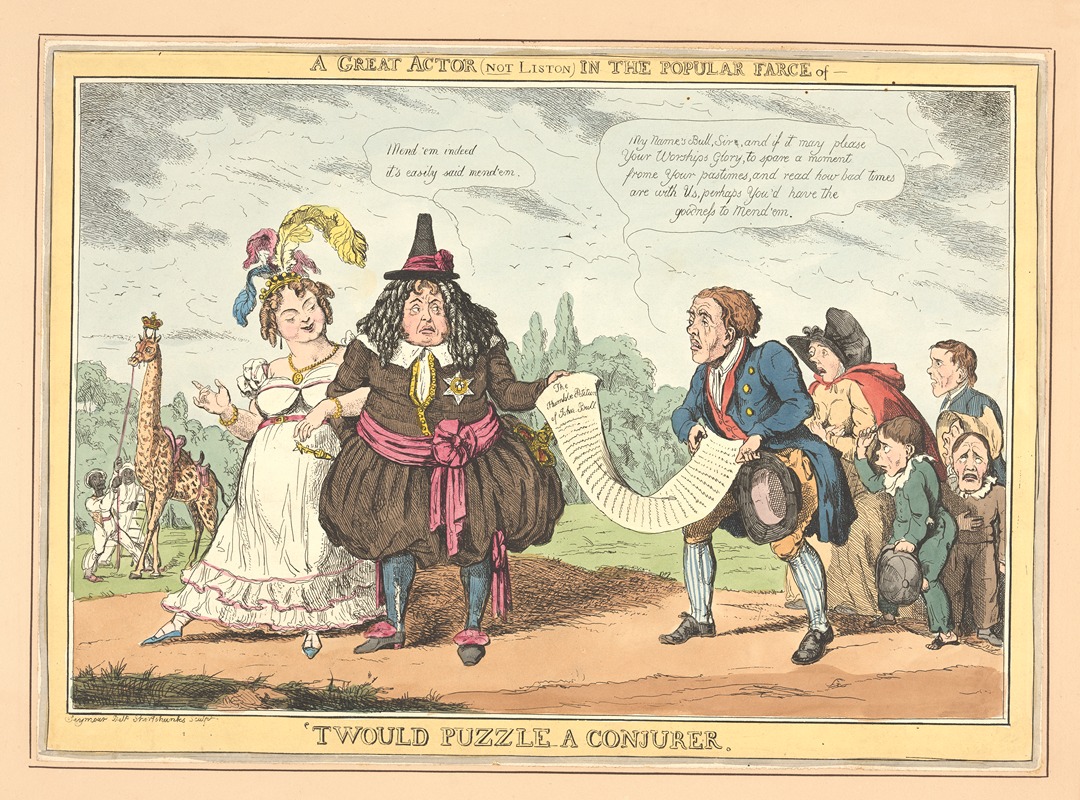

In 1827, Seymour then found steady employment when his etchings and engravings were accepted by the publisher Thomas McLean. Learning to etch on the newly fashionable steel-plates, Seymour then first began to specialize in caricatures and other humorous subjects. In 1830, having mastered the art of etching, Seymour then lithographed separate prints and book illustrations; he was then invited by McLean to produce the 1830 caricature magazine called Looking Glass, as etched throughout by William Heath, for which Seymour produced four large lithographed sheets of illustrations, usually drawn several to a page, every month for the following six years, until his death in 1836.

In 1831, Seymour began work for a new magazine called Figaro in London (pre-Punch), producing 300 humorous drawings and political caricatures to accompany the mundane, political topics of the day and the texts of owner and editor Gilbert à Beckett (1811–56). A cheap weekly, Figaro reflected the clever but abusive character of à Beckett, a friend of Charles Dickens and the publisher of George Cruikshank, who, in 1827, protested at Seymour's parody of his work and nom-de-plume of 'Shortshanks'. Graham Everitt, in English Caricaturists & Graphic Humourists of the Nineteenth Century, (London, 1885), wrote, "The mainstay and prop of the paper from its commencement was Seymour."

In 1834, Gilbert à Beckett failed to pay Seymour what he owed him, and Seymour resigned. A' Beckett replaced him with Cruikshank's brother Robert, and cruelly libelled Seymour in the paper, claiming he had gone insane. Seymour responded by satirising a' Beckett in a rival publication as the very small editor of a very poor paper. Without Seymour, sales of the paper slumped and a' Beckett was declared bankrupt that December. When Henry Mayhew replaced à Beckett as editor of Figaro he enticed Seymour back for the first issue of January, 1835, and Seymour would go on to work harmoniously with Mayhew illustrating Figaro until his death.

Author Joseph Grego, writing sixty-six years after Seymour's death, repeated a claim that arose in the 1880's that a' Beckett's humiliating public smear was attributed as a cause for the coroner's suicide verdict. According to George Somes Layard, writing the entry for Robert Seymour in the 1895-1900 edition of The Dictionary of National Biography this claim was 'contradicted by chronology,' because the dispute between a' Beckett and Seymour occurred several years prior to Seymour's death .

Seymour's eminence as an illustrator now equalled that of his friend George Cruikshank and, as one of the greatest artists since the days of Hogarth, Sir Richard Phillips, predicted that, if he lived, he would become President of the Royal Academy. In 1834, at the height of his prosperity, Seymour launched a new series of lithographs, Sketches by Seymour (1834–36), all depicting expeditions of over-equipped and under-trained Cockneys pursuing cats, birds and stray pigs on foot and on horseback, as experienced in his 1827 fishing and shooting expeditions with his friend Cruickshank.

Seymour died on 20 April 1836, aged 37 or 38, at home in Islington. He was found early that morning by his kitchen maid lying in the garden behind his summer house, killed by a gunshot wound to the chest. His fowling piece, a muzzle-loading shotgun, was found close by, as was a brief letter, unsigned and unaddressed, which was taken to be a suicide note. As reported by The Times of 22 April and The Reformer of 25 April, a coronial inquest the next day found that Seymour had taken his own life while temporarily deranged. Four decades later, illustrator Robert William Buss stated, incorrectly, that Seymour had shot himself in the head. Buss may have taken this from an erroneous report in the weekly sporting newspaper Bell's Life in London that appeared some days after Seymour's death.

Three days earlier, Seymour had called at Dickens's lodgings at Furnival's Inn, Holborn, and they had discussed the artwork for the chapter on the dying clown story. They had a few drinks (grog) then disagreed, after which Seymour left.

It was later claimed that, in a fit of madness, Seymour then burned all his correspondence relating to The Pickwick Papers. This was repudiated by Frederick Kitton in his 1901 reprint of Mrs Jane Seymour's Origins of the Pickwick Papers, in which he revealed that Dickens wrote two letters to Seymour and both survived within the Seymour family. Seymour's son Robert sold one of these letters, the often quoted Dickens missive criticising Seymour's drawing of 'The Dying Clown,' via auction at Sotheby's in 1889.