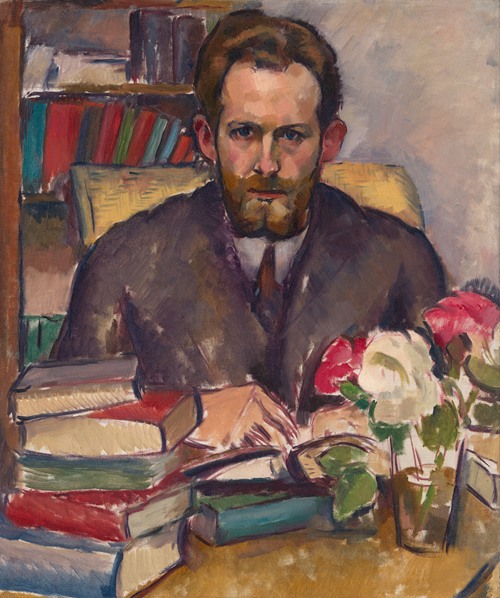

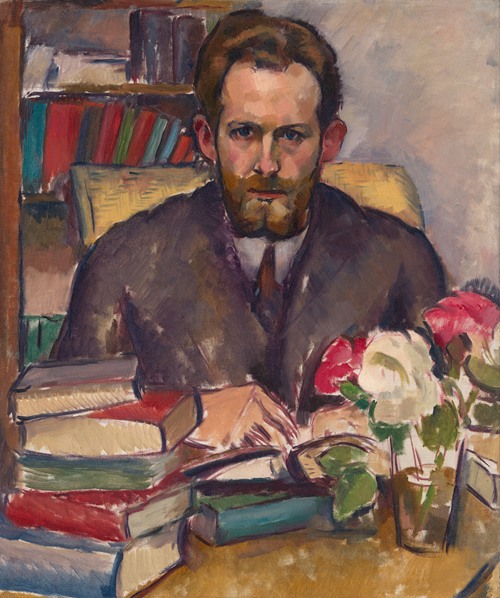

Stanton Macdonald-Wright, was a modern American artist. He was a co-founder of Synchromism, an early abstract, color-based mode of painting, which was the first American avant-garde art movement to receive international attention.

Stanton Macdonald-Wright was born in Charlottesville, Virginia in 1890. His first name, Stanton, was chosen to honor the women's rights activist Elizabeth Cady Stanton; he later hyphenated his last name after repeatedly being asked if he were related to the famed architect Frank Lloyd Wright. He spent his adolescence in Santa Monica, California, where his father ran a seaside hotel. An amateur artist as well as a businessman, Macdonald-Wright's father encouraged his artistic development from a young age and secured him private painting lessons. Stanton's older brother, Willard Huntington Wright, was a writer and critic who gained international fame in the 1920s by writing the Philo Vance detective novels under the pseudonym S.S. Van Dine.

Married at the age of seventeen, Macdonald-Wright moved to Paris with his wife to immerse himself in European art and to study at the Sorbonne, the Académie Julian, the École des Beaux-Arts and the Académie Colarossi. He and fellow student Morgan Russell studied with Canadian painter Percyval Tudor-Hart between 1911 and 1913. They were deeply influenced by their teacher's color theory, which connected the qualities of color to those of music, as well as by the works of Delacroix, the Impressionists, Cézanne, and Matisse that placed a great emphasis on juxtapositions and reverberations of color. During these years Macdonald-Wright and Russell developed Synchromism (meaning "with color"), seeking to free their art form from a literal description of the world and believing that painting was a practice akin to music that should be divorced from representational associations. Macdonald-Wright collaborated with Russell in painting abstract "synchromies" and staged Synchromist exhibitions in Munich in June 1913, in Paris in October 1913, and in New York in March 1914. These established Synchromism as an influence in modern art well into the 1920s, though followers of other abstract artists (principally, the Orphists Robert and Sonia Delaunay) were later to claim that the Synchromists had merely borrowed the principles of color abstraction from Orphism, a point vehemently disputed by Macdonald-Wright and Russell. While in Europe, Macdonald-Wright met Matisse, Rodin, and Gertrude and Leo Stein, and Thomas Hart Benton, who called Stanton "the most gifted all-around fellow I ever knew". He and Russell returned to the United States hopeful of acclaim and financial success and were eager to promote their cause.

In 1915, Stanton's brother, by that time a respected editor and critic in the New York literary world, published one of the first and most comprehensive surveys of advanced art to appear in the United States. Secretly co-authored by Stanton, Modern Painting: Its Tendency and Meaning reviews the major art movements of the previous century from Manet to Cubism, praises the work of Cézanne (still largely unknown in the United States), and predicts a time, soon to come, when an abstract art of pure color will supplant realism. Synchromism itself, the subject of a lengthy, adulatory chapter, is presented as that desired end-point, the culmination of the modernist struggle, surpassing the work of "lesser Moderns" like Kandinsky and the Futurists; at no time does the author acknowledge his own brother as one of the two originators of that school of art.

About his work in this period, Macdonald-Wright commented, "I strive to divest my art of all anecdote and illustration and to purify it to the point where the emotions of the spectator will be wholly aesthetic, as when listening to good music....I cast aside as nugatory all natural representation in my art. However, I still adhered to the fundamental laws of compsiition (placements and displacements of mass, as in the human body in movement) and created my pictures by means of color-form, which, by its organization in three dimensions, resulted in rhythm."

Not long after returning to New York, Macdonald-Wright separated from Russell but both continued to work in the Synchromist style, or with Synchromist color effects, though Macdonald-Wright's painting came to include more vestiges of representational imagery. They held another Synchromist exhibition in New York in 1916 and received significant promotion and critical support from Willard. In 1916, Willard and Stanton were key organizers of the prestigious "Forum Exhibition of Modern American Painters" in New York. Macdonald-Wright exhibited his work at Alfred Stieglitz's famed 291 gallery in New York in 1917. Yet the sales and the renown that he had hoped for did not materialize, and his financial situation grew desperate.

Acknowledging that he would never be able to secure a living in New York, Macdonald-Wright moved to Los Angeles in 1918. In 1920, with Stieglitz's support, he organized the first exhibition of modern art in Los Angeles, "The Exhibition of American Modernists" at the Los Angeles County Museum of History, Science, and Art, showing his own large-scale abstract synchromies as well as works by John Marin, Arthur Dove, and Marsden Hartley. In 1922, he became the head of the Los Angeles Art Students League. He also became involved in local theater, serving as the director of the Santa Monica Theater Guild as well as writing and directing plays, designing sets, and acting himself.

Macdonald-Wright was a significant presence and a charismatic personality in the Los Angeles art scene for the next several decades. He was the director of the Southern California division of the Works Project Administration Federal Art Project from 1935 to 1943, and personally completed several major civic art projects, including the murals in Santa Monica City Hall. After World War II, Macdonald-Wright became interested in Japanese art and culture, which led to the renewal of synchromist elements in his work. He taught art for many years at UCLA and also kept studios in Kyoto and Florence.

By the early 1950s, Macdonald-Wright's work had fallen into relative obscurity. A renewed interest in American modernism led to his gradual rediscovery and new scholarly attention, and he was given retrospectives at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art in 1956, at the Smithsonian National Collection of Fine Arts in Washington, D.C. in 1967, and at the Art Galleries of UCLA in 1970. "Synchromism and American Color Abstraction: 1910–1925," a 1978–1979 six-museum traveling exhibition originating at the Whitney Museum of American Art, was a watershed event in a revival of interest in Synchromism. In 2001–2002, a major Stanton Macdonald-Wright retrospective was shown at the North Carolina Museum of Art, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, and the Houston Museum of Fine Arts, curated by the Synchromist scholar and Macdonald-Wright biographer Will South.

Married three times, Macdonald-Wright died in Pacific Palisades, California in 1973, at the age of eighty-three. His paintings are in the permanent collection of the Museum of Modern Art, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Whitney Museum of American Art, the Brooklyn Museum, the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, and the National Portrait Gallery, among other museums.