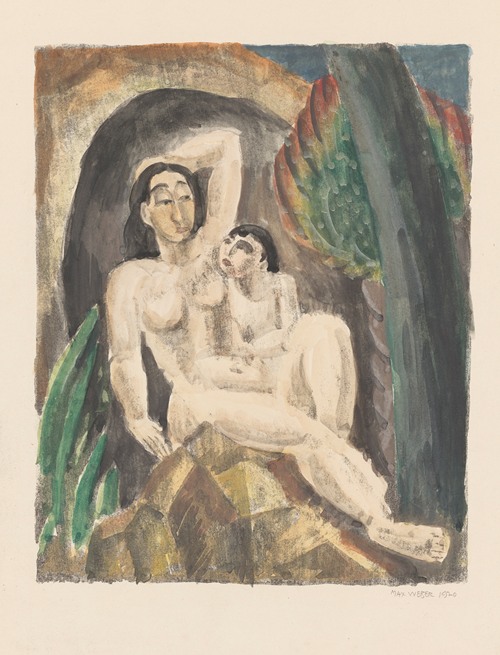

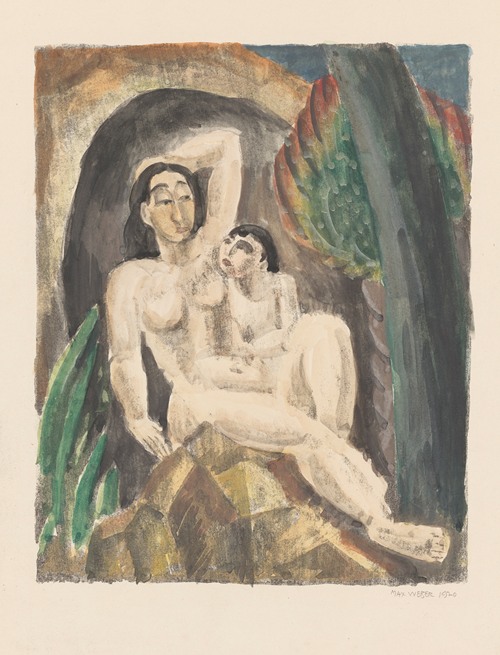

Max Weber was a Jewish-American painter and one of the first American Cubist painters who, in later life, turned to more figurative Jewish themes in his art. He is best known today for Chinese Restaurant (1915), in the collection of the Whitney Museum of American Art, "the finest canvas of his Cubist phase," in the words of art historian Avis Berman.

Born in the Polish city of Białystok, then part of the Russian Empire, Weber emigrated to the United States and settled in Brooklyn with his Orthodox Jewish parents at the age of ten. He studied art at the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn under Arthur Wesley Dow. Dow was a fortunate early influence on Weber as he was an "enlightened and vital teacher" in a time of conservative art instruction, a man who was interested in new approaches to creating art. Dow had met Paul Gauguin in Pont-Aven, was a devoted student of Japanese art, and defended the advanced modernist painting and sculpture he saw at the Armory Show in New York in 1913.

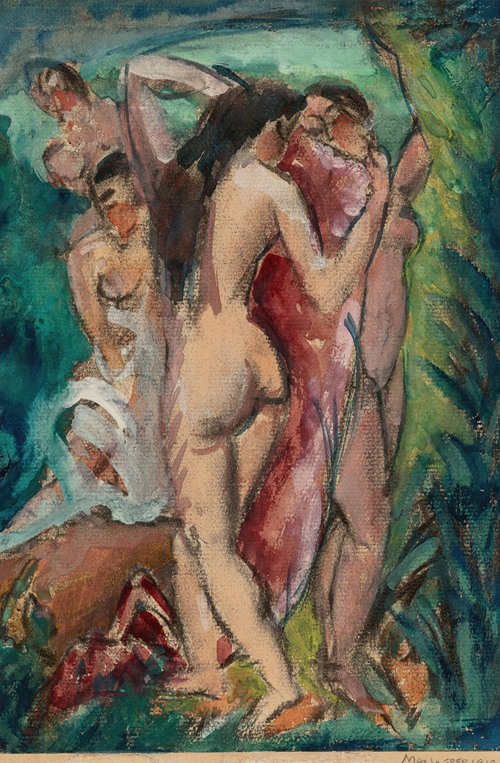

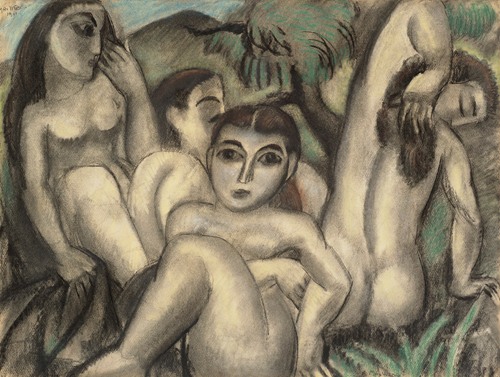

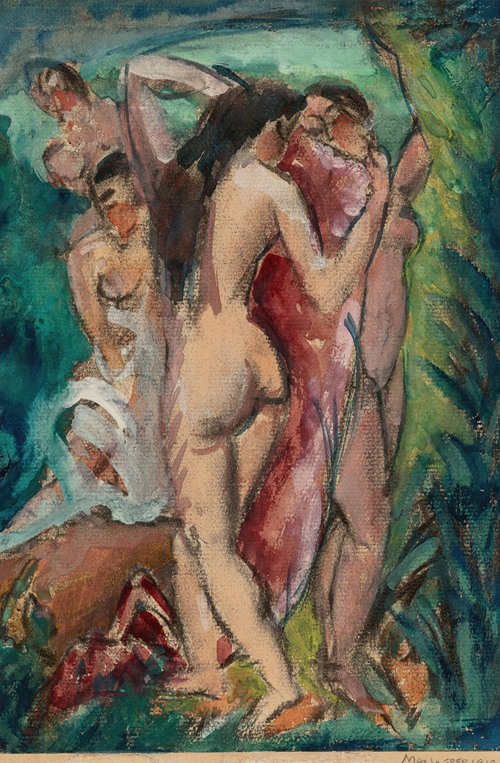

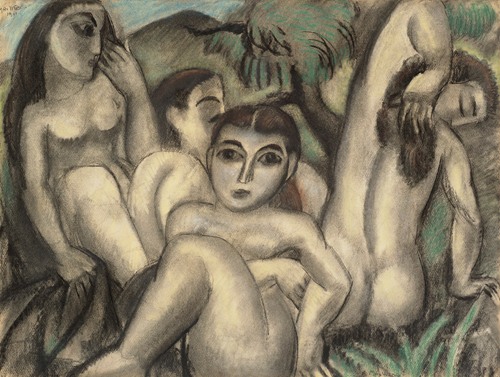

In 1905, after teaching in Virginia and Minnesota, Weber had saved enough money to travel to Europe, where he studied at the Académie Julian in Paris and acquainted himself with the work of such modernists as Henri Rousseau (who became a good friend), Henri Matisse, Pablo Picasso, and other members of the School of Paris. His friends among fellow Americans included some equally adventurous young painters, such as Abraham Walkowitz, H. Lyman Sayen, and Patrick Henry Bruce. Avant-garde France in the years immediately before World War I was fertile and welcoming territory for Weber, then in his early twenties. He arrived in Paris in time to see a major Cézanne exhibition, meet the poet Guillaume Apollinaire, frequent Gertrude Stein's salon, and enroll in classes in Matisse's private "Academie." Rousseau gave him some of his works; others, Weber purchased. He was responsible for Rousseau's first exhibition in the United States.

In 1909 he returned to New York and helped to introduce Cubism to America. He is now considered one of the most significant early American Cubists, but the reception his work received in New York at the time was profoundly discouraging. Critical response to his paintings in a 1911 show at the 291 gallery, run by Alfred Stieglitz, was an occasion for "one of the most merciless critical whippings that any artist has received in America." The reviews were "of an almost hysterical violence." He was attacked for his "brutal, vulgar, and unnecessary art license." Even a critic who usually tried to be sympathetic to new art, James Gibbons Huneker, protested that the artist's clever technique had left viewers with no real picture and made use of the adage, "The operation was successful, but the patient died." As art historian Sam Hunter wrote, "Weber's wistful, tentative Cubism provided the philistine press with their first solid target prior to the Armory Show."

Weber was sustained by the respect of some eminent peers, such as photographers Alvin Langdon Coburn and Clarence White, and museum director John Cotton Dana, who saw to it that Weber was the subject of a one-man exhibition at the Newark Museum in 1913, the first modernist exhibition in an American museum. For a few years, Weber enjoyed a productive if rocky relationship with Stieglitz, and he published two essays in Stieglitz's journal Camera Work. (He also wrote Cubist poems and published a book, Essays on Art, in 1916.) So poor was Weber in these years that he camped out for some weeks in Stieglitz's gallery. Weber was also closely acquainted with Wilhelmina Weber Furlong and Thomas Furlong, whom he met at the Art Students League, where he taught from 1919 to 1921 and 1926 to 1927. Weber died in Great Neck, New York in 1961. He was the subject of a major retrospective at the Jewish Museum in 1982.

Weber evidently was a prickly personality even with his allies. He and Stieglitz had a falling-out, and Weber was not represented in the famous Armory Show because his friend, Arthur B. Davies, one of the show's organizers, had only allotted him space for two paintings. In a fit of pique at Davies, he withdrew entirely from the exhibition. Other artists in the Stieglitz circle kept their distance, especially after Weber told people that there were only three indisputably great modern painters: Cézanne, Rousseau, and himself. "Almost without exception, they found him obnoxious: opinionated, rude, intolerant."

In time, Weber's work found more adherents, including Alfred H. Barr, Jr., the first director of the Museum of Modern Art. In 1930, the Museum of Modern Art held a retrospective of his work, the first solo exhibition at that museum of an American artist. He was praised as a "pioneer of modern art in America" in a 1945 Life magazine article. In 1948, Look magazine reported on a survey among art experts to determine the greatest living American artists; Weber was rated second, behind only John Marin. He was the subject of a major traveling retrospective in 1949. He became more popular in the 1940s and 1950s for his figurative work, often expressionist renderings of Jewish families, rabbis, and Talmudic scholars, than for the early modernist work he had abandoned circa 1920 and on which his current reputation is founded.

Not everyone believed that Weber fulfilled his early potential as he became a more representational and expressionist painter post-World War I. Critic Hilton Kramer wrote of him that, in light of the remarkable beginning of his career, "Weber proved instead to be one of the great disappointments of twentieth-century American art." Others however, because of his bold "Cubist decade," hold him in the same high regard as other native modernists like John Marin, Arthur Dove, Marsden Hartley, and Charles Demuth.