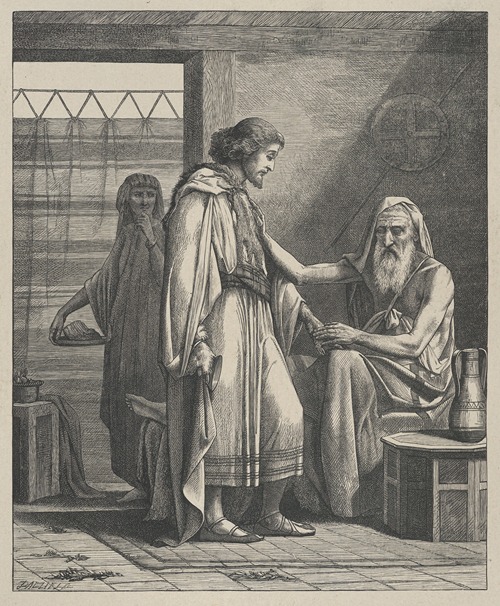

![Moses Destroys the Tables [Tablets]](https://mdl.artvee.com/ft/936264il.jpg)

Edward Armitage was an English Victorian-era painter whose work focused on historical, classical and biblical subjects.

Armitage was born in London to a family of wealthy Yorkshire industrialists, the eldest of seven sons of James Armitage (1793–1872) and Anne Elizabeth Armitage née Rhodes (1788–1833), of Farnley Hall, just south of Leeds, Yorkshire. His great-grandfather James (1730–1803) bought Farnley Hall from Sir Thomas Danby in 1799 and in 1844 four Armitage brothers, including his father James, founded the Farnley Ironworks, utilising the coal, iron and fireclay on their estate. His brother Thomas Rhodes Armitage (1824–1890) founded the Royal National Institute of the Blind.

Armitage was the uncle of Robert Armitage (MP), the great-uncle of Robert Selby Armitage, and first cousin twice removed of Edward Leathley Armitage.

Armitage's art training was undertaken in Paris, where he enrolled at the École des Beaux-Arts in October 1837. He studied under the history painter, Paul Delaroche, who at that time was at the height of his fame. Armitage was one of four students selected to assist Delaroche with the fresco Hémicycle in the amphitheatre of the Palais des Beaux-Arts, when he reputedly modelled for the head of Masaccio. Whilst still in Paris, he exhibited Prometheus Bound in 1842, which a contemporary critic described as 'well drawn but brutally energetic'.

In 1843 Armitage returned to London, where he entered competitions for the decoration of the new Palace of Westminster, the old Houses of Parliament having been destroyed by fire in 1834. To organise and oversee this project, a Royal Commission had been appointed in 1841, the President of which was Queen Victoria's new Consort, Prince Albert. Decorations were to be executed in fresco and were to illustrate subjects from British history or from the works of Spenser, Shakespeare or Milton. Competitions were held for appropriate designs ('cartoons'), with a number of leading artists commissioned to take part. The first competition entries were unveiled in Westminster Hall in the summer of 1843 and attracted considerable attention from the public. Armitage's cartoon, The Landing of Julius Caesar in Britain, secured one of the three first prizes of £300. He won a further prize in 1845 in a subsequent Westminster competition for his cartoon The Spirit of Religion. Although neither of these cartoons was executed in fresco, Armitage did execute two frescoes in the Poets' Gallery off the Upper Waiting Hall: The Thames and its Tributaries (also referred to as The Personification of the Thames) (1852), from the poetry of Alexander Pope; and The Death of Marmion (1854), from Sir Walter Scott's poem. Unfortunately frescoes were ill-suited to the atmosphere of 19th-century London, and many started to disintegrate almost as soon as they were completed.

Armitage won one of the first-class premiums in 1847 for his oil painting The Battle of Meanee, which was subsequently purchased by Queen Victoria. In this battle, General Sir Charles Napier brought the provinces of Sindh under the dominion of Great Britain, an account of which was written by his brother, Sir William Napier. Armitage consulted both brothers for detailed information on the battle and he used sketches of the locality lent by Sir Charles. However, the painting was the subject of much controversy, with doubts expressed that the war had been justified. The 1847 The Art Union review concluded with the following: "Notwithstanding the great ability displayed by Mr. Armitage in this production, which of its class, has never been excelled in England, we cannot but regret that he did not select a theme more purely historical - one more honourable to our nation than the slaughter of thousands - of whom, after all, we were the oppressors". Thackeray, writing in Punch under the pseudonym of Professor Byles, also disapproved of the subject-matter: "With respect to the third prize - a Battle of Meeanee - in this extraordinary piece they are stabbing, kicking, cutting, slashing, and poking each other about all over the picture. A horrid sight! I like to see the British lion mild and good-humoured ... not fierce, as Mr. Armitage has shown him."

In 1848 Armitage exhibited for the first time at the Royal Academy when he showed two paintings, Henry VIII and Catherine Parr, and Trafalgar (also known as The Death of Nelson). He continued to send contributions most years until his death. These included Retribution (1858), Esther's Banquet (1865) (also known as Festival of Esther), The Remorse of Judas (1866), Herod's Birthday Feast (1868), A Deputation to Faraday (1871), Julian the Apostate (1875), Pygmalion's Galatea (1878), Meeting of St. Francis and St. Dominic (1882), Faith (1884), The Siren (1888), and a portrait of his brother The late T.R. Armitage, M.D., the Friend of the Blind (1893).

Probably the best known of these is Armitage's huge imperialistic painting, Retribution, in which he allegorized the suppression and punishment of the Indian 'Mutiny' by Great Britain in 1857. This was painted after details of the massacre of British soldiers, women and children had been circulated by the press. The Illustrated London News of 1859 described Retribution thus: "Britannia, represented of colossal proportions, has seized the assassin tiger by the throat, and is about to plunge her sword into its heart ... The melancholy results of the mutiny, which have spread mourning through so many homes, are typified in the figures of prostrate victims, with debris of books, etc., scattered around."

Armitage was elected an associate of the Royal Academy in 1867 and a full member in 1872, and in 1875 he was appointed Professor and Lecturer on painting. His lectures to the Royal Academy were published as Lectures on Painting (London and New York, 1883).

On 3 February 1853 Armitage married Catherine Laurie Barber, also an artist. They were among the first artists to settle in the St John's Wood area of London, and their friends included other artists in the neighbourhood.

After retiring from the Royal Academy in May 1894, Armitage spent some time in Royal Tunbridge Wells for the benefit of his health. He lodged at Mount Edgcumbe House, where he died on 24 May 1896 of apoplexy and exhaustion following pneumonia. He is buried in Hove Cemetery.

![Moses Destroys the Tables [Tablets]](https://mdl.artvee.com/ft/936264il.jpg)