Claude Fayette Bragdon

Claude Fayette Bragdon was an American architect, writer, and stage designer based in Rochester, New York, up to World War I, then in New York City.

The designer of Rochester’s New York Central Railroad terminal (1909–13) and Chamber of Commerce (1915–17), as well as many other public buildings and private residences, Bragdon enjoyed a national reputation as an architect working in the progressive tradition associated with Louis Sullivan and Frank Lloyd Wright. Along with members of the Prairie School and other regional movements, these architects developed new approaches to the planning, design, and ornamentation of buildings that embraced industrial techniques and building types while reaffirming democratic traditions threatened by the rise of urban mass society. In numerous essays and books, Bragdon argued that only an “organic architecture” based on nature could foster democratic community in industrial capitalist society.

Bragdon was born in Oberlin, Ohio. He was raised in Watertown, Oswego, Dansville and Rochester, New York, where his father worked as a newspaper editor. After working for architects in Rochester, New York City, and Buffalo, Bragdon went into practice in Rochester. His major buildings include the city's New York Central Railroad Station, the Rochester First Universalist Church, Bevier Memorial Building, Shingleside, and the Rochester Italian Presbyterian Church, among many others. At Oswego he designed the Oswego Yacht Club. He designed an addition to the Romanta T. Miller House in 1914.

While Bragdon's early work reflected the revival of Renaissance architecture associated with the City Beautiful, he soon became a leading participant in the arts and crafts movement, working with Harvey Ellis, Gustav Stickley, and other arts and crafts artists. Around 1900, Bragdon embraced the ideas of Louis Sullivan and began to reorient his work toward the midwestern ideal of a progressive architecture based on nature. His version of organic architecture, however, reflected different social and cultural values than did those of either Sullivan or Bragdon's contemporary Frank Lloyd Wright. Whereas for Sullivan and Wright a building was most organic when it expressed the individual character of its creator, Bragdon saw individualism as a hindrance to the formation of a consensual democratic culture. Accordingly, he promoted regular geometry and musical proportion as ways for architects to harmonize buildings with one another and with their urban context. From 1900 until he closed his architectural practice during World War I, Bragdon applied these principles to his buildings, and he continued to use them through the 1920s in both graphic designs and the theatrical sets he created during a second career as a New York stage designer.

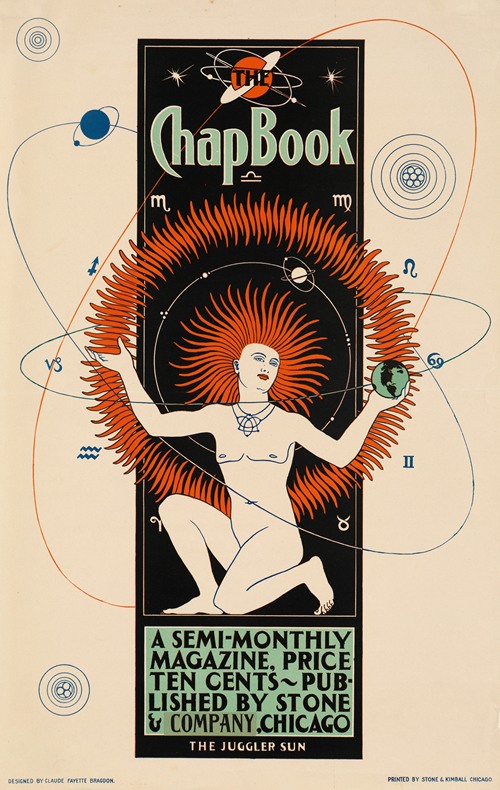

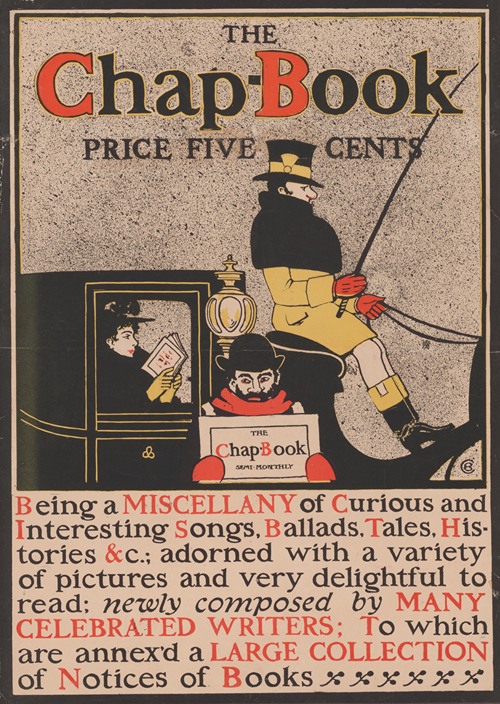

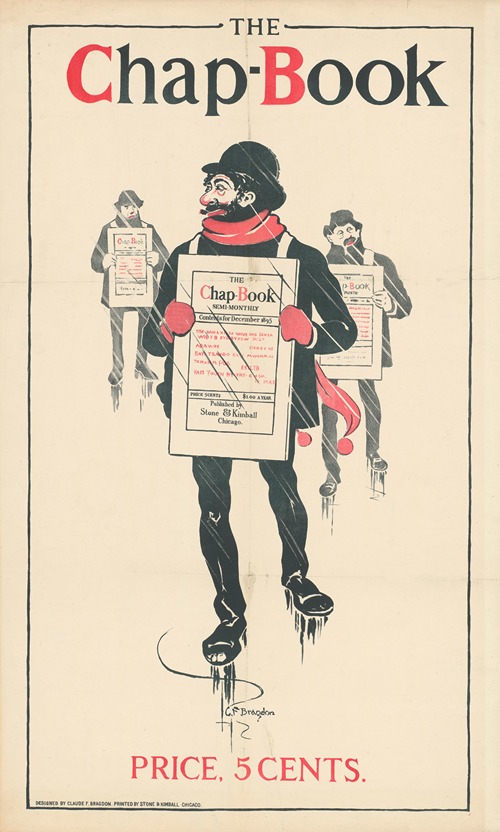

Bragdon was well regarded for his ink rendering talent, his many very successful designs for both residential and institutional buildings, and his inventive geometric ornament. His most important contribution to both architectural modernism and progressive reform came in 1915 with his creation of a new ornamental vocabulary he called “projective ornament.” Projective ornament was a system for generating geometric patterns that could be adapted for use in architecture, the fine and decorative arts, and graphic design. Basing ornament on mathematical patterns abstracted from nature, Bragdon created a universal form-language to replace the variety of historical and national styles, which provided designers and clients with a vocabulary for articulating differences of class, culture, gender, nationality, and religion. By showing how his repertory of patterns could be adapted to any kind of design problem, Bragdon aimed to integrate not only architecture, art, and design, but also his divided society.

Bragdon's ornament appeared in the Rochester Chamber of Commerce (1915–17), as well as in the design of magazines, posters, and books. It spread throughout the region through its use in a series of Festivals of Song and Light that Bragdon staged with community music reformers from 1915 to 1918 in Rochester, Buffalo, Syracuse, and New York. These nocturnal community chorus festivals incorporated ornamental lamps and decorations into massive public events that drew tens of thousands of spectator-participants. Through its role in both civic architecture and print media, projective ornament began to integrate these distinct realms into a single public sphere visually unified by geometric pattern.

In 1917, after a dispute with photography magnate George Eastman (of Eastman Kodak fame) over the design of the Rochester Chamber of Commerce Building, Bragdon's architectural practice waned. He incorporated his own design of the hypercube in the structure of the building. He moved to New York City in 1923 and became a stage designer, and remained in New York until his death in 1946. In 1925, knowing Alfred Stieglitz and having been introduced to Margaret Lefranc (Frankel), an eighteen-year-old American studying in Paris and Berlin, Bragdon took her to Stieglitz to show her art. Bragdon and Lefranc remained friends for the remainder of his life while his influences rounded out her education. In his books on architectural theory, The Beautiful Necessity (1910), Architecture and Democracy (1918), and The Frozen Fountain (1932), he advocated a theosophical approach to building design, urging an "organic" Gothic style (which he thought of as reflective of the natural order) over the "arranged" Beaux-Arts architecture of the classical revival. He had yet another overlapping career as an author of books on spiritual topics, including Eastern religions. These books include Old Lamps for New (1925), Delphic Woman (1925), The Eternal Poles (1931), Four Dimensional Vistas (1930), and An Introduction to Yoga (1933). His autobiography More Lives Than One (1938) alludes to both his belief in reincarnation and his varied career paths.

In 1920, he helped translate and publish P.D. Ouspensky's Tertium Organum, for which he also wrote an introduction to the English translation.

Bragdon’s work fell out of favor in the 1930s as American architects and clients embraced International Style modernism. But it left an ongoing legacy as younger architects—in particular Buckminster Fuller, who adapted some of Bragdon’s ideas and designs—found new ways of using geometric pattern to promote architectural and social integration.