Charles Allan Gilbert, better known as C. Allan Gilbert, was a prominent American illustrator. He is especially remembered for a widely published drawing (a memento mori or vanitas) titled All Is Vanity. The drawing employs a double image (or visual pun) in which the scene of a woman admiring herself in a mirror, when viewed from a distance, appears to be a human skull. The title is also a pun, as this type of dressing-table is also known as a vanity. The phrase "All is vanity" comes from Ecclesiastes 1:2 ("Vanity of vanities, saith the Preacher, vanity of vanities; all is vanity.") It refers to the vanity and pride of humans. In art, vanity has long been represented as a woman preoccupied with her beauty. And art that contains a human skull as a focal point is called a memento mori (Latin for "remember death"), a work that reminds people of their mortality.

It is less widely known that Gilbert was an early contributor to animation, and a camouflage artist (or camoufleur) for the U.S. Shipping Board during World War I.

Born in Hartford, Connecticut, Gilbert was the youngest of the three sons of Charles Edwin Gilbert and Virginia Ewing Crane. As a child, he was an invalid (the circumstances of which are unclear), with the result that he often made drawings for self-amusement (Leonard 1913).

At age sixteen, he began to study art with Charles Noel Flagg, the official portrait painter for the State of Connecticut, who had also founded the Connecticut League of Art Students. In 1892, he enrolled at the Art Students League of New York, where he remained for two years. In 1894, he moved to France for a year, where he studied with Jean-Paul Laurens and Jean-Joseph Benjamin-Constant at the Academie Julien in Paris (New York Times 1913).

Returning from Paris, Gilbert settled in New York, where he embarked on an active career as an illustrator of books, magazines, posters and calendars. His illustrations were frequently published in Scribner's, Harper's, Atlantic Monthly and other leading magazines. It was earlier, while he was still a student at the Art Students' League, that he completed All Is Vanity, the drawing that became popular when it was initially published in Life magazine in 1902.

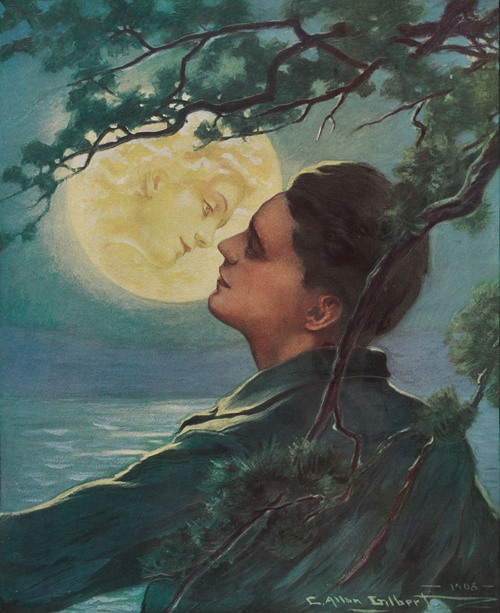

In the course of his artistic career, Gilbert illustrated a large number of books, among them Ellen Glasgow's Life and Gabriella (1916), H.G. Wells' The Soul of a Bishop (1917), Gouverneur Morris' His Daughter (1919), Edith Wharton's The Age of Innocence (1920), and Booth Tarkington's Gentle Julia (1922). He also published collections of his own drawings, including Overheard in the Whittington Family, Women of Fiction, All is Vanity, The Honeymoon, A Message from Mars, and In Beauty's Realm.

As an early contributor to animated films (Grant, p. 49), Gilbert worked for John R. Bray in 1915–16 on the production of a series of moving shadow plays called Silhouette Fantasies. These Art Nouveau-styled films, which were made by combining filmed silhouettes with pen-and-ink components, were serious interpretations of Greek myths (Crafton 1993, p. 865; Bachman 2002, pp. 261–262).

During World War I, Gilbert served as a camouflage artist for the U.S. Shipping Board (the Emergency Fleet Corporation), as did other well-known artists and illustrators, including McClelland Barclay, William MacKay, and Henry Reuterdahl (Behrens 2009). As did they, he also illustrated posters for American wartime programs such as Liberty Bonds (or Liberty Loans).

Throughout his life (and still today), Gilbert was so strongly identified with his drawing All Is Vanity that he is sometimes mistakenly credited with two other popular double image artworks, Gossip: And the Devil Was There, and Social Donkey, both of which were apparently made by another illustrator of the same time period, George A. Wotherspoon.

Gilbert continued to live in New York during the remainder of his life, but he often spent his summers on Monhegan Island in Maine. He died in New York of pneumonia at age 55.