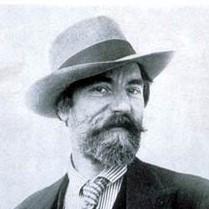

Augustus Edwin John OM RA was a Welsh painter, draughtsman, and etcher. For a time he was considered the most important artist at work in Britain: Virginia Woolf would remark that by 1908 the era of John Singer Sargent and Charles Wellington Furse "was over. The age of Augustus John was dawning." He was the younger brother of the painter Gwen John.

Born in Tenby, Pembrokeshire, John was the younger son and third of four children. His father was Edwin William John, a Welsh solicitor; his mother, Augusta Smith from a long line of Sussex master plumbers, died young when he was six, but not before inculcating a love of drawing in both Augustus and his older sister Gwen. At the age of seventeen he briefly attended the Tenby School of Art, then left Wales for London, studying at the Slade School of Art, University College London. He became the star pupil of drawing teacher Henry Tonks and even before his graduation he was considered the most talented draughtsman of his generation. His sister, Gwen was with him at the Slade and became an important artist in her own right.

In 1897, John hit submerged rocks diving into the sea at Tenby, suffering a serious head injury; the lengthy convalescence that followed seems to have stimulated his adventurous spirit and accelerated his artistic growth. In 1898, he won the Slade Prize with Moses and the Brazen Serpent. John afterward studied independently in Paris where he seems to have been influenced by Pierre Puvis de Chavannes.

Over a period of two years from around 1910 Augustus John and his friend James Dickson Innes painted in the Arenig valley, in particular one of Innes's favourite subjects, the mountain Arenig Fawr. In 2011 this period was made the subject of a BBC documentary titled The Mountain That Had to Be Painted.

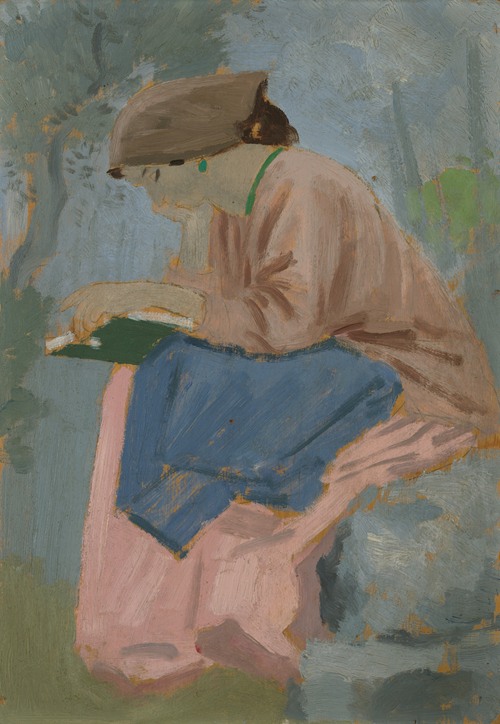

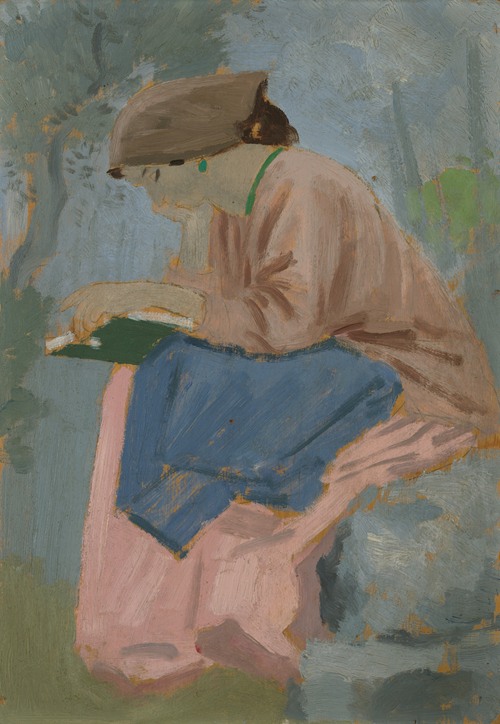

In February 1910, John visited and fell in love with the town of Martigues, in Provence, located halfway between Arles and Marseilles, and first seen from a train en route to Italy. John wrote that Provence "had been for years the goal of my dreams" and Martigues was the town for which he felt the greatest affection. "With a feeling that I was going to find what I was seeking, an anchorage at last, I returned from Marseilles, and, changing at Pas des Lanciers, took the little railway which leads to Martigues. On arriving my premonition proved correct: there was no need to seek further." The connection with Provence continued until 1928, by which time John felt the town had lost its simple charm, and he sold his home there.

John was, throughout his life, particularly interested in the Romani people (whom he referred to as "Gypsies"), and sought them out on his frequent travels around the United Kingdom and Europe, learning to speak various versions of their language. For a time, shortly after his marriage, he and his family, which included his wife Ida, mistress Dorothy (Dorelia) McNeill, and John's children by both women, travelled in a caravan, in gypsy fashion. Later on he became the President of the Gypsy Lore Society, a position he held from 1937 until his death in 1961.

In December 1917 John was attached to the Canadian forces as a war artist and made a number of memorable portraits of Canadian infantrymen. The end result was to have been a huge mural for Lord Beaverbrook and the sketches and cartoon for this suggest that it might have become his greatest large-scale work. However, like so many of his monumental conceptions, it was never completed. As a war artist, John was allowed to keep his beard and he and King George V were the only Army officers in the Allied forces to have facial hair, apart from pioneer sergeants and those who were allowed unshaven for medical reasons. After two months in France he was sent home in disgrace after taking part in a brawl. Lord Beaverbrook, whose intervention saved John from a court-martial, sent him back to France where he produced studies for a proposed Canadian War Memorial picture, although the only major work to result from the experience was Fraternity. In 2011, the Duke and Duchess of Cambridge finally unveiled this mural at the Canadian War Museum in Ottawa. This unfinished painting, The Canadians Opposite Lens, is 12 feet high by 40 feet long.

Although known early in the century for his drawings and etchings, the bulk of John's later work consisted of portraits. Those of his two wives and his children were regarded as among his best. He was known for the psychological insight of his portraits, many of which were considered "cruel" for the truth of the depiction. Lord Leverhulme was so upset with his portrait that he cut out the head (since only that part of the image could easily be hidden in his vault) but when the remainder of the picture was returned by error to John there was an international outcry over the desecration.

By the 1920s John was Britain's leading portrait painter. John painted many distinguished contemporaries, including T. E. Lawrence, Thomas Hardy, W. B. Yeats, Aleister Crowley, Lady Gregory, Tallulah Bankhead, George Bernard Shaw, the cellist Guilhermina Suggia, the Marchesa Casati and Elizabeth Bibesco. Perhaps his most famous portrait is of his fellow-countryman, Dylan Thomas, whom he introduced to Caitlin Macnamara, his sometime lover who later became Thomas' wife. Portraits of Dylan Thomas by John are held by the National Museum Wales and the National Portrait Gallery.

Early in 1901, John married Ida Nettleship (1877–1907), daughter of the artist John Trivett Nettleship, and a fellow student at the Slade; the couple had five sons. From 1905 until her death in 1907 Ida lived in Paris with John's mistress Dorothy "Dorelia" McNeill; a Bohemian style icon, she lived with John for the rest of their lives, having four children together, though they never married. One of his sons (by his wife Ida) was the prominent British Admiral and First Sea Lord Sir Caspar John. His daughter with Dorelia, Vivien John (1915–1994), was a notable painter.

By Ian Fleming's widowed mother, Evelyn Ste Croix Fleming, née Rose, he had a daughter, Amaryllis Fleming (1925–1999), who became a noted cellist. Another of his sons, by Mavis de Vere Cole, wife of the prankster Horace de Vere Cole, is the television director Tristan de Vere Cole. His son Romilly (1906–1986) was in the RAF, briefly a civil servant, then a poet, author and an amateur physicist. Poppet (1912–1997), John's daughter by Dorothy, married the Dutch painter Willem Jilts Pol (1905–1988). Willem Pol's daughter Talitha (1940–1971) by an earlier marriage (i.e. step-granddaughter of both Augustus and Dorothy), a fashion icon of 1960s London, married John Paul Getty Jr.. His daughter Gwyneth Johnstone (1915–2010), by musician Nora Brownsword, was an artist. Augustus John's promiscuity gave rise to rumours that he had fathered as many as 100 children.

In later life, John wrote two volumes of autobiography, Chiaroscuro (1952) and Finishing Touches (1964). In old age, although John had ceased to be a moving force in British art, he was still greatly revered, as was demonstrated by the huge show of his work mounted by the Royal Academy in 1954. He continued to work up until his death in Fordingbridge, Hampshire in 1961, his last work being a studio mural in three parts, the left hand of which showed a Falstaffian figure of a French peasant in a yellow waistcoat playing a hurdy-gurdy while coming down a village street. It was Augustus John's final wave goodbye.

Early in his career John became a leading figure in the New English Art Club, where he frequently exhibited in the years up to the First World War. With his vivid manner of portraiture and his ability to catch unerringly some striking and usually unfamiliar aspect of his subject, he superseded Sargent as England's fashionable portrait painter. In 1921 he was elected an Associate of the Royal Academy and elected a full R.A. in 1928. He was named to the Order of Merit by King George VI in 1942. He was a trustee of the Tate Gallery from 1933 to 1941, and President of the Royal Society of Portrait Painters from 1948 to 1953. He was awarded the Freedom of the Town of Tenby on 30 October 1959. His reputation came to exceed his talents: on his death in 1961 an obituary in The New York Times observed, 'He was regarded as the grand old man of British painting, and as one of the greatest in British history.'