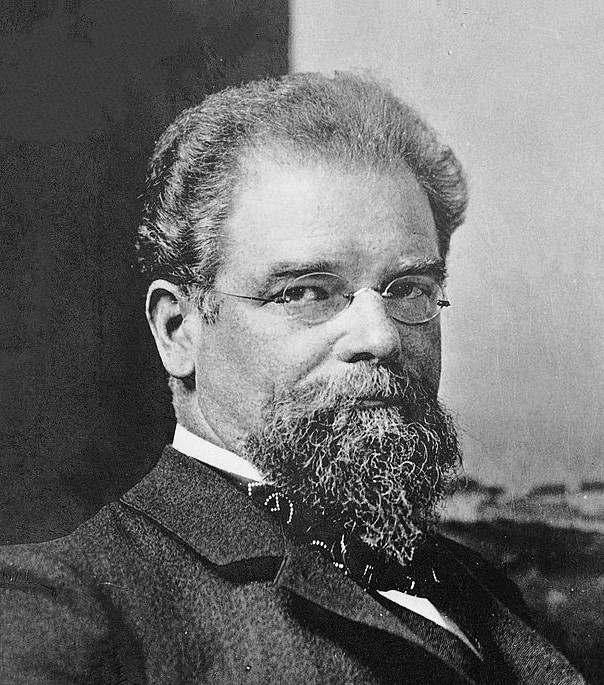

Max Klinger was a German artist who produced significant work in painting, sculpture, prints and graphics, as well as writing a treatise articulating his ideas on art and the role of graphic arts and printmaking in relation to painting. He is associated with symbolism, the Vienna Secession, and Jugendstil (Youth Style) the German manifestation of Art Nouveau. He is best known today for his many prints, particularly a series entitled Paraphrase on the Finding of a Glove and his monumental sculptural installation in homage to Beethoven at the Vienna Secession in 1902.

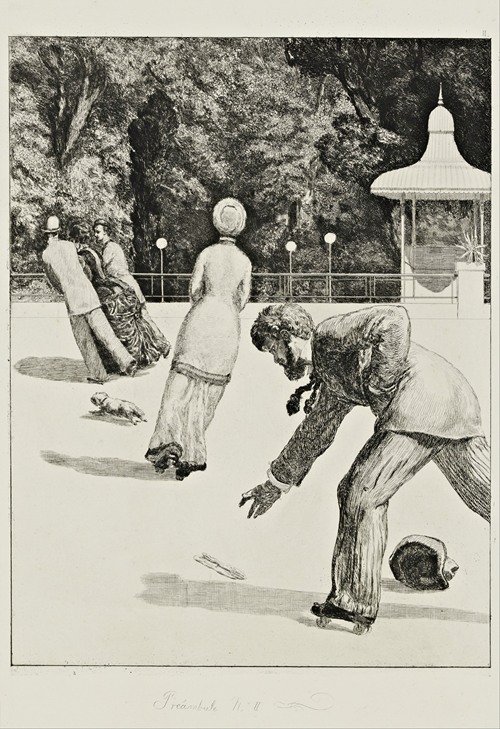

Klinger was born in Leipzig, Germany to a wealthy and prominent family. He enrolled in the Academy of Fine Arts in Karlsruhe in 1874 where he was a pupil of Karl (or Carl) Gussow. When Gussow left Karlsruhe to become the Director of the Academy of Fine Arts in Berlin, Klinger moved to Berlin as well to complete his studies there. Klinger shared a studio with Christian Krohg and the two had a mutual admiration for French naturalist authors like Émile Zola and Gustave Flaubert, who explored the shadowy aspects of urban life and the hypocrisy of society and the bourgeoisie in their novels. At that time realism was the prevailing style in Germany and Arnold Böcklin was one of the few artist active there that Klinger felt a close affinity to. Klinger graduated from the Academy in 1877. He was drawn to and studied the etchings and prints of many masters that were more aligned with his sensibilities including Dürer, Rembrandt, Goya, Runge, Menzel, and Rops. He begin an apprenticeship studying engraving under Hermann Sagert and soon became a skilled and imaginative engraver in his own right. Klinger visited Brussels for a time in 1879, and the following year he spent time in Munich. He was achieving some notoriety with his pen and ink drawings and prints when in 1881 he published two sets of etchings, including Paraphrase on the Finding of a Glove, which was an immediate success and established his reputation.

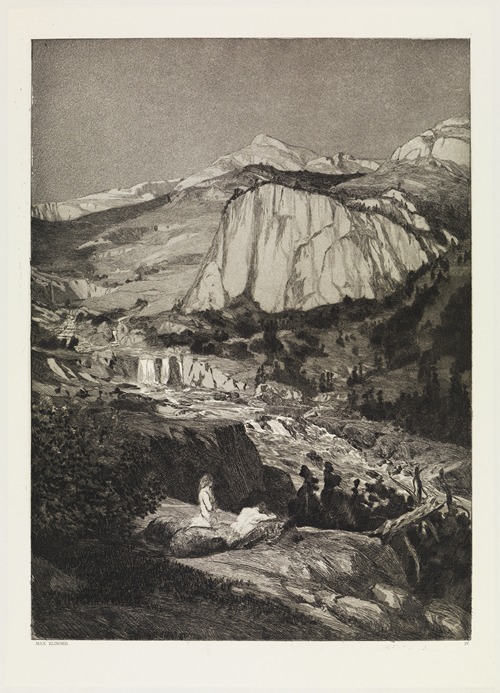

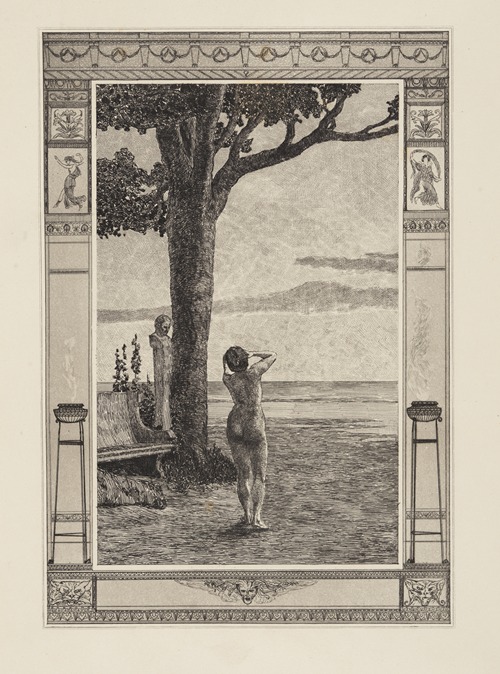

With a receptive audience developing in Paris, where the Franco-Uruguayan poet and art critic Jules Laforgue had been celebrating and advocating his prints, Klinger moved to Paris in 1883 where he lived until 1886 or 1887. Klinger first began sculpting about 1883, and sculpture slowly came to dominate his output in his later years. He conceived and started work on his Beethoven sculpture while in Paris but, it was not completed and fully realized until 1902. In 1889 Les XX (The Twenty) invited Klinger to exhibit his work in their annual winter exhibition that year in Brussels. He moved to Rome in 1889, staying until 1893, studying the Italian masters, where the 15th century artists and works from antiquity are said to have been something of a revelation to him. He also intensified his studies of anatomy, the nude, and the representation of mass and volume during this period of his life. It was a productive time in his career. In the 1890s, Klinger continued his gradual shift away from printmaking in favor of sculpting.

Klinger was an accomplished pianist and counted the composer Max Reger among his friends. A friendship with the composer Johannes Brahms developed over a period of 20 years, culminating with Klinger's publication of his print series Brahms Fantasies (1894) and Brahms's dedication of Vier ernste Gesänge (Four Serious Songs), Opus 121, to Klinger in 1896, a year before the composer's death.

In 1906 he founded the Villa Romana Prize. After buying a villa in Florence, complete with 15,000 square meter park, recipients of the prize were given the opportunity to stay for a few months and adsorbed the culture of the city. The first beneficiary of the prize was Gustav Klimt, however Klimt waived his honor and passed it on to Maximilian Kurzweil. Later recipients included Käthe Kollwitz, Max Beckmann, Ernst Barlach and Georg Kolbe.

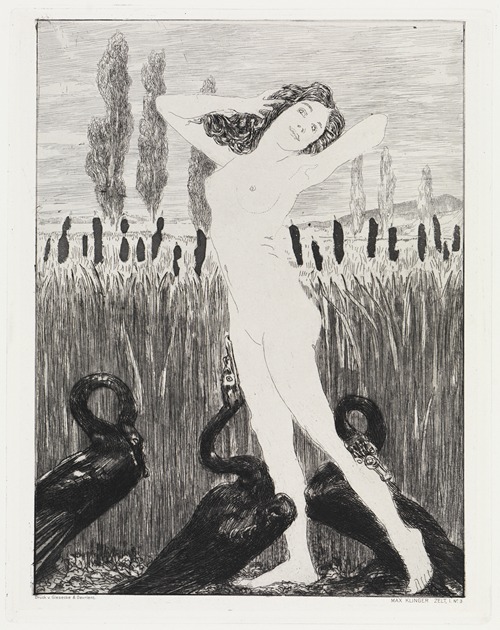

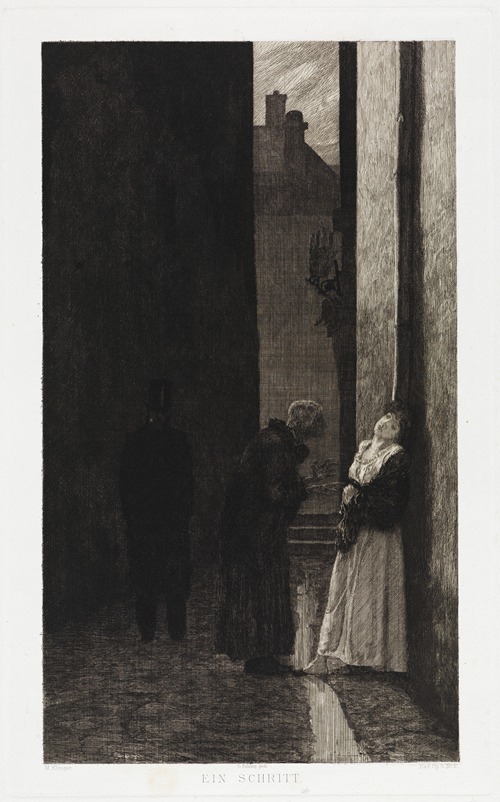

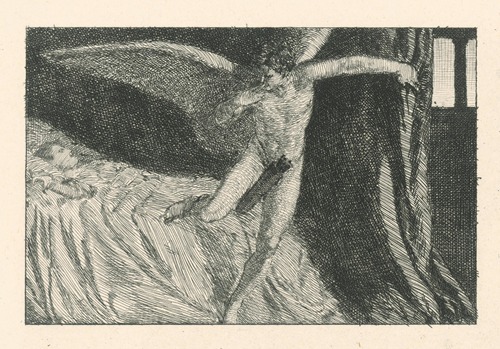

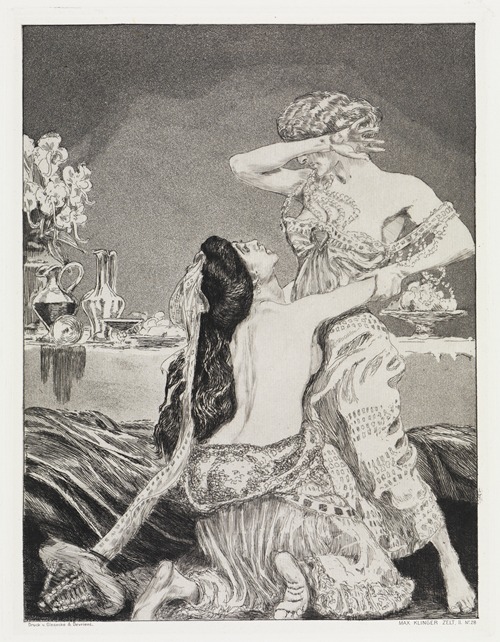

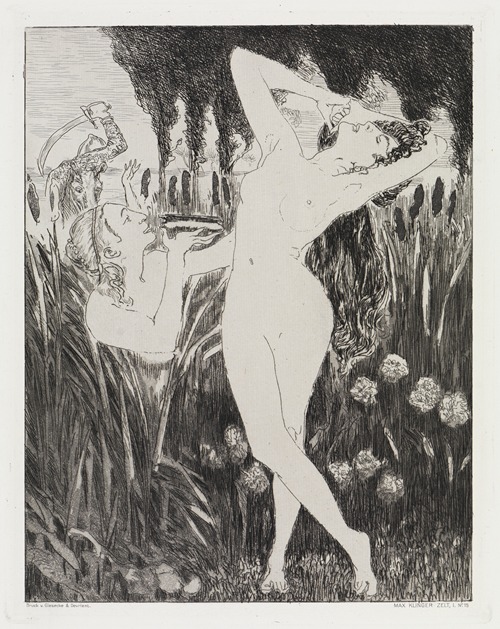

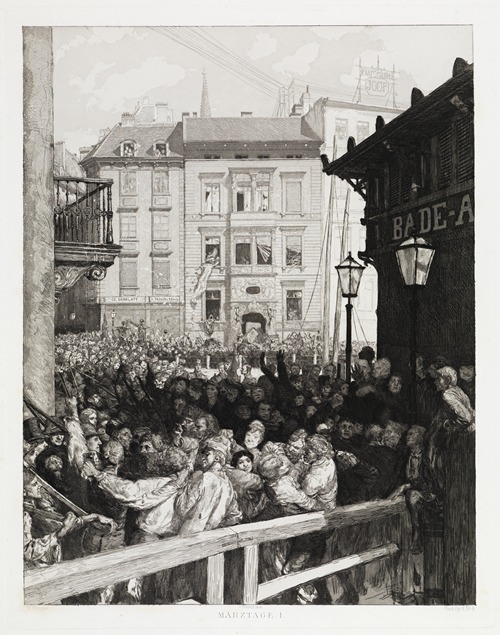

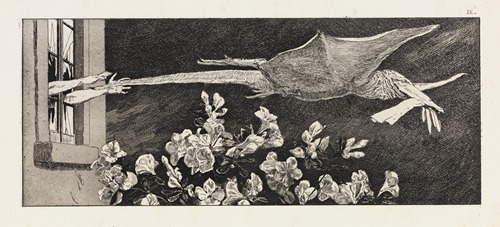

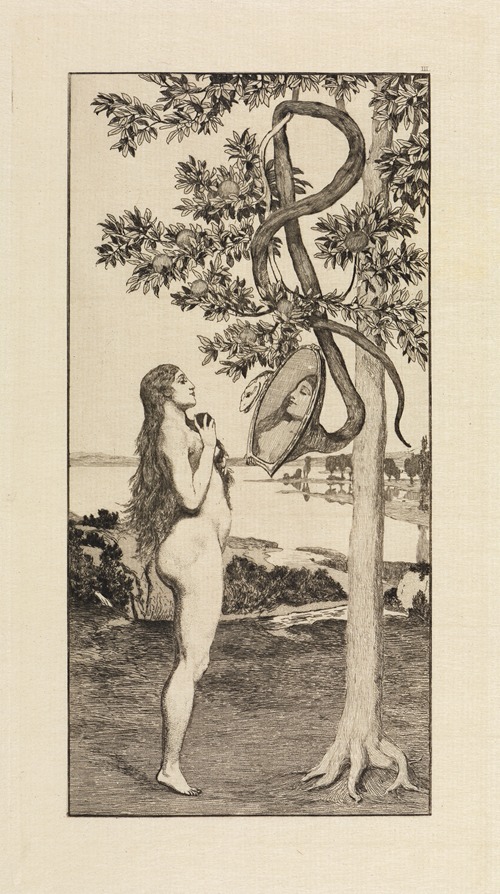

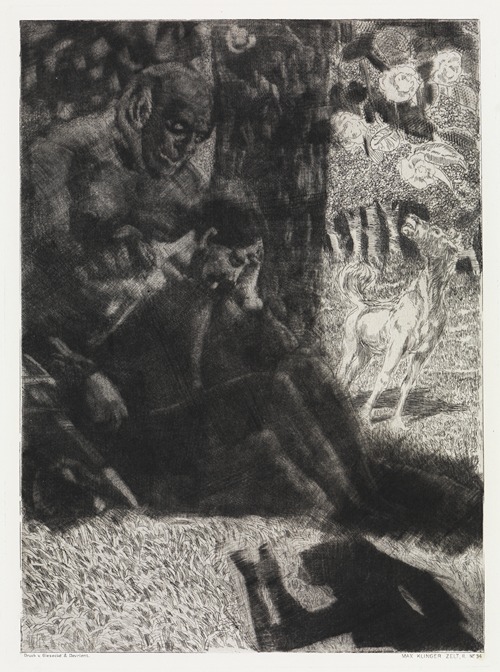

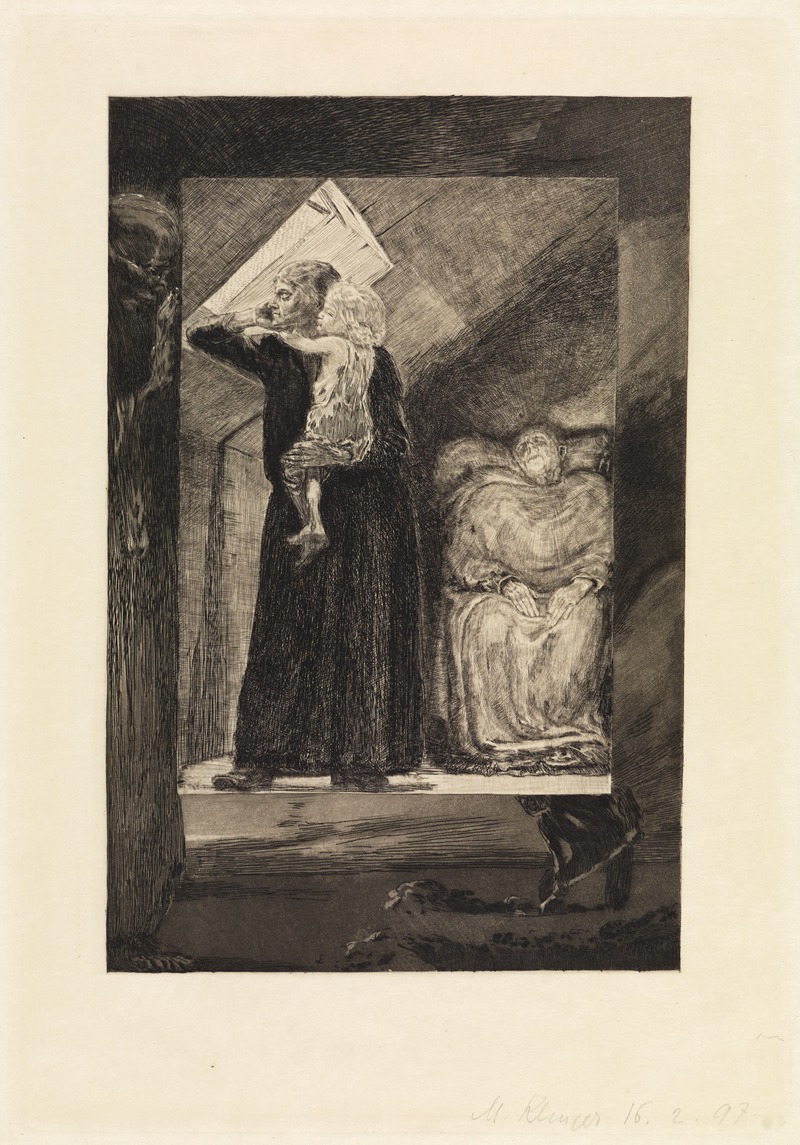

A significant portion of Klinger’s reputation is associated with his many cycles and series of intaglio prints, which influenced numerous printmakers and artist of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Klinger would adeptly intergraded several intaglio media like aquatint, drypoint, and etching in a single plate producing remarkable formal and tonal qualities. The subjects range from esoteric symbolism to darker aspects of realism. In the cycle A Life (1884), Klinger is often regarded as the first German artist to deal with prostitution as a social problem and the hypocrisy and injustices regarding societies attitude to the subject. The series follow a middle-class woman's descent into prostitution: impregnated, deserted, then rejected by society, she descends into the depths of urban life, and ridiculed by an apathetic and indifferent genteel society. The series A Love (1887) was dedicated to Arnold Böcklin another symbolist artist Klinger greatly admired.

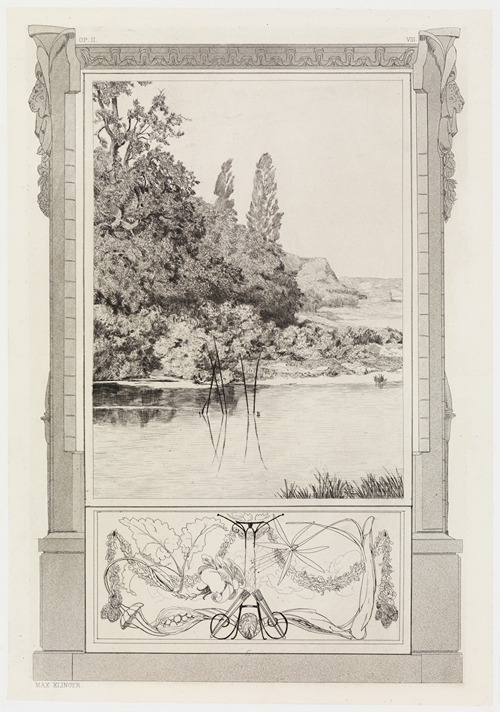

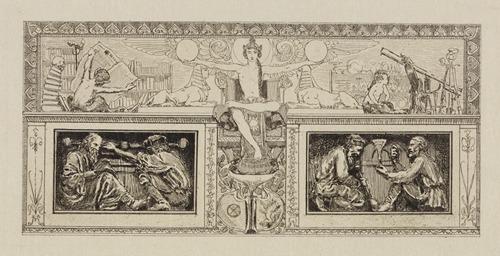

In Paris he started to draft his polemical text for Painting and Drawing, which was eventually published in 1891, and subsequently reissued a number of times. The manuscript was well circulated and well read, with an number of later artist and historians referencing it, including Giorgio de Chirico who called Klinger the "modern artist par excellence". In it Klinger asserted the idea that prints and the graphic arts should have a new and significant role in the arts, distinct from painting, and were best suited for stylistic and conceptual experimentation. Also that the differences between naturalism (realism) and neo-idealism, as well as form and content, were reconcilable, and both were possible. Concepts of the Gesamtkunstwerk, an all-embracing art form, with unity among the arts (e.g. painting, sculpture, literature, poetry, music, etc.), were also discussed.

Klinger had a lifelong passion for music and musical elements are often reflected and expressed in his art. His print cycles were given opus numbers, typically associated with musical publications. His series Brahms Fantasies (1894) was intended to be an amalgamation of music, poetry, and the visual arts: to be viewed with a performance of the composer’s music, creating Gesamtkunstwerk or "all-embracing art form". Klinger produced sculptures of Beethoven, Brahms, and Liszt as well.

Inspired by recent accounts of archaeological discoveries of antique sculptural remains made from various colored stones, Klinger utilized a variety of materials in many of his sculptures. A mixture of bronze, ivory, alabaster, and several different marbles were used in Beethoven. He studied and took measurements of Beethoven's death mask in Vienna and traveled to Laas in southwestern France to personally select the alabaster, and the Pyrenees and Syra (or Syros), Greece to select marbles. Elsa Asenijeff wrote of the unusually complex and difficult process involved with casting the large bronze throne from wax in her book Max Klinges Beethoven: Eine kunst-technische Studie (Max Klinge's Beethoven: A Practical Artistic Study) published in 1902. The sculpture was exhibited in an earlier stage of development in Paris in 1885 and later rejected from major exhibitions in Berlin 1887 and 1888. It developed something of a cult-like reputation over the years.

Klinger was cited by many artists (notably Giorgio de Chirico) as being a major link between the symbolist movement of the 19th century and the start of the metaphysical movement. His work was also admired and a formative influence on later artist such as Max Ernst and other surrealist artist. The historian Holger Jacob-Friesen illustrates and discusses in detail the influence of Klinger's prints on artist such as Franz von Stuck, Kathe Kollwitz, Edward Munch, Lovis Corinth, Otto Greiner, Alfred Kubin, Max Slevogt, Paul Klee, Richard Müller, Oskar Kokoschka, Max Beckmann, Horst Janssen, as well as De Chirico and Ernst.